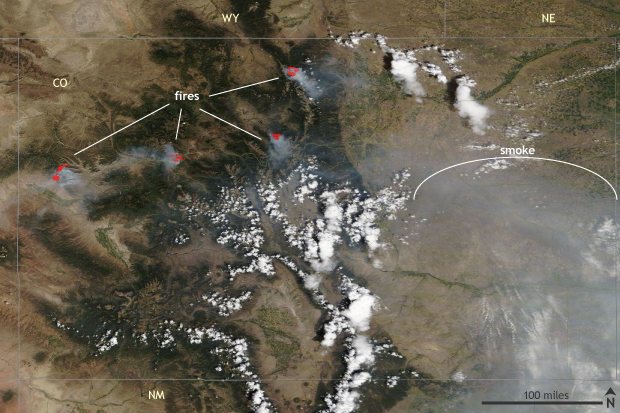

Multiple large wildfires have broken out across western Colorado during July and August, burning hundreds of thousands of acres, shutting down highways, and billowing smoke hundreds of miles across the state. With the fires located in remote areas, containing them across rugged terrain has been difficult. Several are expected to continue to burn for the foreseeable future.

NASA MODIS Terra satellite image of fires and smoke across Colorado on August 16, 2020. Red outlines indicate areas where satellite sensors detected the heat signature of active fires. Image courtesy NASA Earth Observatory.

The four largest wildfires in the state have, as of August 19, burned through over 170,000 acres of western Colorado. The largest fire, the Pine Gulch Fire, was started by lightning on July 31 near Grand Junction. It has burned over 125,000 acres and is the second largest in state history. It remains only 7% contained as of August 19.

Three other not-fully-contained wildfires make up the remaining ~50,000 burned acres: the Grizzly Creek (over 27,000 acres burned), Williams Fork (over 6,000 acres), and Cameron Peak fires (over 14,000 acres burned). Luckily, no major damages have been reported with the fires so far, though the Grizzly Creek fire caused the shutdown of parts of Interstate 70. This makes the Grizzly Creek fire one of the most important fires to work on in the state as I-70 is the main road for commercial transportation through the rugged terrain, with limited detour options. The smoke from all of the fires has also led to hazy skies and poor air quality across the state.

Why are wildfires so bad this year?

There is no one single reason why wildfires are so bad one year compared to a past year. Instead, it’s a combination of climate and environmental factors and the randomness of our weather setting the stage for bad luck to happen.

Animation of drought conditions across the United States from the U.S. Drought Monitor from July 2, 2019 to August 11, 2020. The severity of drought conditions increases from yellow (abnormally dry) to light orange (moderate) to orange (severe) to red (extreme) to, finally, maroon (exceptional). Climate.gov map, based on data from the National Drought Monitor project.

Previous horrible wildfire years in 2002, 2012-13 and 2018 all coincided with horrible drought conditions statewide as well. And this year is no different. At least a quarter of the state has been in drought since October 2019, with almost 94% in drought now, of which nearly 24% is categorized as extreme or exceptional drought, the two worst categories. The lack of rain has also coincided with a hot summer in Colorado, following a generally warmer-than-average 2020, so far. The end result of little moisture and hot temperatures is a lot of dry vegetation.

Making matters worse, last year’s spring and summer were wetter than average in Colorado. This meant that coming into 2020 there was more vegetation available to dry out and become wildfire fuel.

But there was yet another environmental factor in play as well. Over the last several decades, Colorado has been hard hit by bark beetles leading to the die off of many trees in the state—according to the Fourth National Climate Assessment, bark beetle infestations killed 7% of western U.S. forest areas from 1979-2012. So even before the lush spring, there was already abundant underlying fuel available for wildfires—the dead bark-beetle infested trees. The climate and environmental factors all pointed to an environment ripe for wildfires this summer.

Pushing the fire risk over the edge has been the hot and dry summer weather. Temperature records all across the West have been falling in August, with the mercury hitting 130°F in Death Valley on August 16. This extreme heat has helped provide the necessary conditions for the continuation and spread of the fires.

The future of wildfires in the West

Just how numerous factors played a role in the wildfire risk for this summer in Colorado, the same goes for the future of wildfire risk in the West as our planet warms due to human-burning of fossil fuels. According to the Climate Science Special Report, the number of large fires has increased from 1984 to 2011, especially over the western United States. The cause was likely due to a combination of reasons including trends in temperature, soil moisture, and vegetation, along with decades of forest management and fire suppression practices.

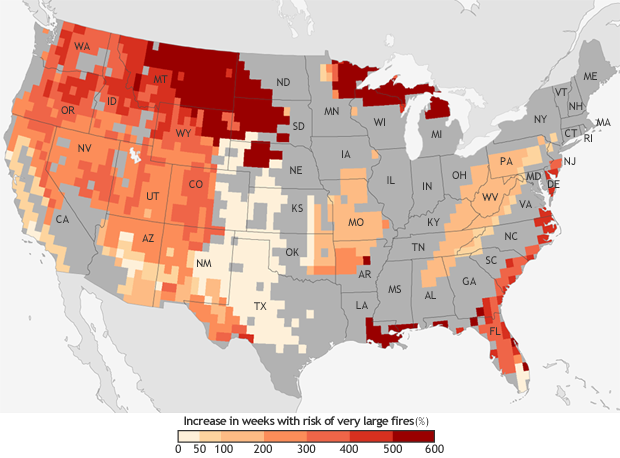

The projected increase in the number of “very large fire" weeks—weeks in which conditions are favorable to the occurrence of very large fires—by mid-century (2041-2070) compared to the recent past (1971-2000). Projections are based on the possible emissions scenario known RCP 8.5, which assumes continued increases in carbon dioxide emissions. NOAA Climate.gov map, based on data from Barbera et al, 2015. More detail.

Looking to the future, research suggests that climate change will cause an increase in very large fires (greater than 50,000 acres, like the Pine Gulch fire) across the western United States by the middle of the century in both a lower and higher greenhouse gas emission scenario. The latest U.S. National Climate Assessment also notes that fire frequency could increase 25% and large fires could triple in frequency specifically across the Southwest.

So even though wildfires are a natural part of the many ecosystems, climate change has driven and likely will continue to drive a wildfire increase. This increase not only can negatively impact human infrastructure but can also damage animal habitat and spread invasive plant species. Plus, the scars left behind by the wildfires can impact water quality and rainfall runoff for many years after the fire.

To know if (or when) your town is under an increased risk for fire, head to the National Weather Service’s Storm Prediction Center for Fire Weather outlooks.