Multiple wildfires in northern and southern California have led to tragedy and devastation in November 2018, with an estimated 66 fatalities (as of November 16) and more than 10,000 lost structures. The fires also sent smoke plumes hundreds of miles away, degrading air quality throughout the state. It’s the second year in a row that the state has experienced massive, destructive wildfires.

Suomi NPP satellite image taken of California on November 9, 2018 using the VIIRS instrument. Smoke from two large fires, the Camp Fire in northern California and the Woolsey Fire in southern California, is being blown offshore by strong easterly winds. NOAA Climate.gov image using data provided by the NOAA Environmental Visualization Laboratory.

Unlike locations East of the Mississippi, California’s precipitation is sharply seasonal, with hot, dry summers and wetter winters. A dry start to the current water year in October came on the heels of an even drier-than-average summer. The resulting dried grasses and vegetation provided plenty of fuel for wildfires to grow exponentially should a fire be lit. And in November, 2018, those wildfire powder kegs exploded in both northern and southern California.

North of Sacramento, the Camp Fire burned an area of over 70,000 acres in less than a day starting on November 8, taking advantage of incredibly dry atmospheric and ground conditions while strong winds whipped the fire into a frenzy. As of November 14, the fire had burned over 138,000 acres of mostly non-forested land and was only 35% contained. The Camp Springs fire now has the dubious record of being both the most destructive and deadliest wildfire in modern history for California.

In southern California, similarly hot, dry and windy conditions helped turn a fire into a raging conflagration in the hills north of Los Angeles. The Woolsey fire also started on November 8 and has burned almost 100,000 acres of mostly grass and shrubs and was 52% contained. The fire has impacted well-known communities north of Los Angeles including Malibu, Calabasas, Agoura Hills, and Thousand Oaks and has burned down over 500 structures as of November 14.

How was California primed for wildfires?

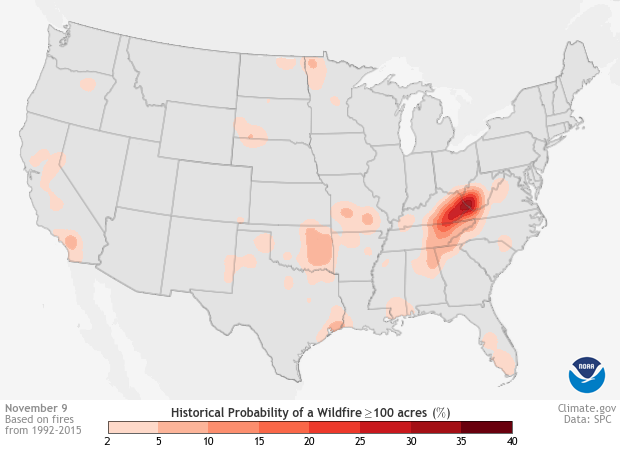

Statistically, the risk for wildfires in California in November is very low, with only areas north of Sacramento and across southern California at a small risk for wildfires bigger than 100 acres.

Climatological risk of wildfires with an area of 100 acres of larger reported within 25 miles for November 9. Climatology was created using a 24-year base period. The darker the shading, the higher the number of fires reported close in time to the displayed date. For California, small risks for wildfires are located in the Central Valley and across southern California. NOAA Climate.gov image using data from NOAA"s National Weather Service Storm Prediction Center.

This makes sense, as wildfire risk peaks in the hot, dry months of summer and then decreases as the chance of seasonal rain increases. Rains across California peak during the winter months, but on average, precipitation begins to pick up starting in October.

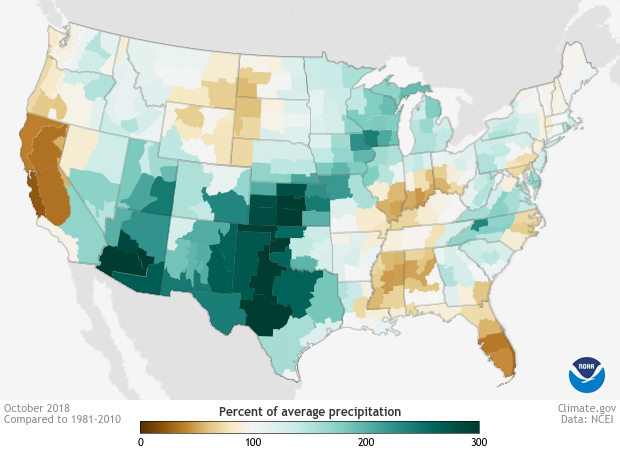

Summer 2018 was much warmer than average across the state—record warm in some places, especially at night—and in Northern California, precipitation ranged from below average to record dry. Precipitation across much of the state was less than 5 percent of average in September, and the summer dry signal extended into beginning of the fall wet season, with below-average precipitation in October as well.

Percent of normal monthly precipitation for October 2018 across the United States. Brown colors reflect drier than average conditions while blues represent wetter than average amounts. Below-average precipitation in California marked a slow start to seasonal rains in the state. Climate.gov image using data from the National Centers for Environmental Information.

With all the heat and dryness, the ground was dry to start November, with vegetation turned into excellent fire fuel. Then strong winds, including the Santa Ana winds in southern California, roared into town. A high pressure system with clockwise winds settled in to the east of California. This allowed winds to blow in from the east, moving down the coastal mountains of California. The winds then got funneled through natural channels in the mountains, gathering speed as they moved down in elevation. As the winds continued to drop in elevation, they compressed and warmed, drying the air even more.

These winds tend to peak during the winter months but occur during the fall as well. Normally, the wetter conditions during the winter rainy season mean these strong winds don’t act to whip up fires. The moistened grounds reduce the risk of fires even starting to begin with. But if rains are below-average and summer-baked ground remains dry, these winds can help rapidly spread fires even into winter.

Both fires saw strong, dry winds blow in from the east as winds gusted to at least 40-50 mph. This rapidly spread the fires and made containment near impossible for firefighters.

Climate Change connection

According to the Climate Science Special Report as a part of the upcoming Fourth National Climate Assessment, the number of large fires has increased from 1984-2011, especially over the western U.S.. These trends are likely from a combination of factors, including previous decades’ fire suppression policies and climate change.

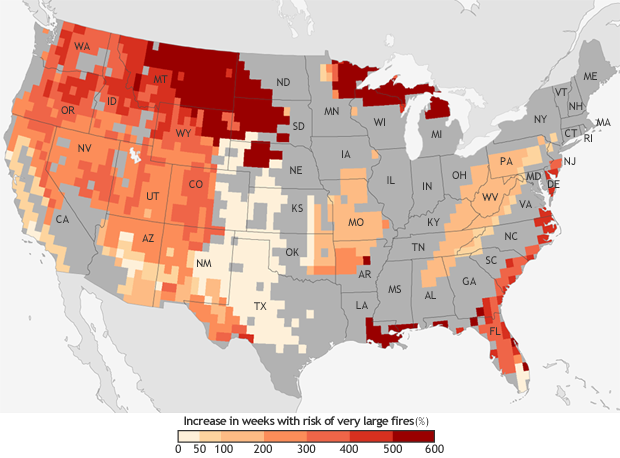

Research suggests that global warming will cause an increase in very large fires—greater than 50,000 acres—across the western United States by the middle of the century under both lower and higher greenhouse gas emission scenarios.

The projected increase in the number of “very large fire" weeks—weeks in which conditions are favorable to the occurrence of very large fires—by mid-century (2041-2070) compared to the recent past (1971-2000). Projections are based on the possible emissions scenario known RCP 8.5, which assumes continued increases in carbon dioxide emissions. NOAA Climate.gov map, based on data from Barbera et al, 2015. More detail.

In the previous U.S. National Climate Assessment, the authors noted that models forecast up to a 74% increase in burned areas in California by the end of the century in scenarios with high greenhouse gas emissions.

This makes sense as warming temperatures due to human-caused climate change will dry out vegetation even more, leaving additional kindling available for fires. To know if (or when) your town is under an increased risk for fire, head to the National Weather Service’s Storm Prediction Center for Fire Weather outlooks.