Under the driving force of fierce winds, deadly wildfires exploded across northern California in the second week of October 2017. According to the Los Angeles Times, at least 17 people had been killed as of October 11, and thousands of homes and other infrastructure—including cell phone towers used by the state’s emergency services—had been destroyed.

Grab and drag slider to view satellites images of California on October 5, 2017 (left, before the fire), and on October 10, 2017 (right), when multiple wildfires raged north of San Francisco. NASA satellite images from Worldview.

The extremely dangerous fire conditions actually began last winter, with near-record precipitation between December 2016-February 2017. The drought-busting amounts of precipitation re-stocked the state’s snowpack, which had been heavily depleted by 6 years of drought.

The wet winter fostered “megablooms” of desert wildflowers and ushered in a lush growing season. Unfortunately, the climate swung to a different extreme. The state’s second-wettest winter on record was followed by its hottest summer. Baked to tinder in the extreme heat, the abundant vegetation of spring became the kindling for these autumn fires.

Winter (December–February) precipitation (top) and summer (June–August) average temperature in California from 1896-2017. NOAA Climate.gov graphs, based on data from NCEI's Climate at a Glance tool.

Thanks to the interplay between human-caused global warming, the legacy of historic fire suppression policies, and natural variability in drought cycles, California and the rest of the U.S. Southwest are likely to face this kind of devastating fire season even more often in the second half of this century.

According to the U.S. National Climate Assessment:

Between 1970 and 2003, warmer and drier conditions increased burned area in western U.S. mid-elevation conifer forests by 650% (Ch. 7: Forests, Key Message 1).…Models project…up to a 74% increase in burned area in California, with northern California potentially experiencing a doubling under a high emissions scenario toward the end of the century.

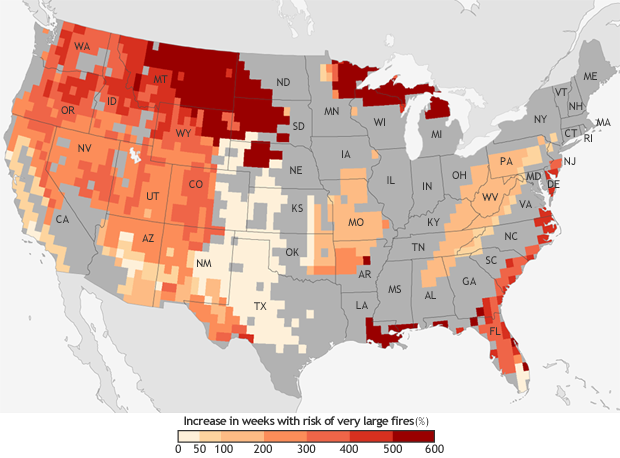

According to an analysis done in 2015, the number of weeks in the year during which climate conditions in Northern California are favorable for very large fires will double or quadruple by mid-century (2041-2070) compared to the recent past (1971-2000) if carbon dioxide emissions remain high. In other parts of the West, the risk of extremely dangerous fire weather conditions may increase six fold.

The projected increase in the number of “very large fire" weeks—weeks in which conditions are favorable to the occurrence of very large fires—by mid-century (2041-2070) compared to the recent past (1971-2000). Projections are based on the possible emissions scenario known RCP 8.5, which assumes continued increases in carbon dioxide emissions. NOAA Climate.gov map, based on data from Barbera et al, 2015. More detail.