Wildfires have broken out across southwestern Colorado this June, burning thousands of acres in the San Juan National Forest and nearby private lands. The largest fire in southwestern Colorado, dubbed the 416 fire, has affected more than 33,000 acres (36 square miles) of land and was only 30% contained as of June 18.

Click and drag the slider in the center of the image to compare. (left) Sentinel satellite image of the 416 Fire in southern Colorado on June 10, 2018, in infrared-enhanced false color. Actively burning areas appear bright yellow, vegetation appears bright green, and burned areas appear reddish brown. (right) Same view in photo-like natural color, which better shows the smoke plume spreading north and east from the fire. Images courtesy Sentinel Online/European Space Agency.

According to the Denver Post, this fire, located about 16 miles north of Durango, led to the closure of San Juan National Forest for the first time in its 113-year history. The National Interagency Fire Center estimates that suppression costs are up to $17.3 million as of June 18. The fire got started during the beginning of month and grew rapidly, taking advantage of favorable fire conditions.

One of those conditions is the presence of plenty of fuel in the form of dry plants. It has been painfully dry in the Four Corners region of the country for quite a while. This part of Colorado in particular has been suffering through the worst category of drought (D4 or Exceptional Drought) for the last two months and some form of drought since November 2017.

U.S. drought conditions on January 8, February 13, March 13, and April 17, color coded from yellow (abnormally dry) to dark red (exceptional drought). NOAA Climate.gov animation, based on data from the US Drought Monitor project.

Fortunately, some rain fell over the fire area over the weekend, which enabled scientists at the National Weather Service’s Storm Prediction Center to lower the fire weather risk. The 3-8-day outlook for critical fire weather issued on June 17 indicated no areas of elevated risk for several days.

Wildfire climatology in the Four Corners

The best chance of a wildfire in the southwestern United States occurs during the early summer months, peaking in early July. It is then that the desert southwest is sweltering under the summer sun, but still waiting for the rains of the North American Monsoon. This dry heat creates a relatively short window of peak fire risk that stretches from late June through the middle of July.

Afterwards, rains associated with the North American Monsoon normally begin to roll into the area. We have written before about the devastating flash floods that can accompany the Southwest monsoon (as it is known in the United States), but these showers also provide enough moisture to reduce (though not eliminate) the risk of wildfires, especially across mountainous terrain, where rainfall is often the highest.

Future wildfire risk

As has been noted in previous Event Tracker articles about wildfires across the United States, the nature of wildfires is already changing. In particular, the number of large wildfires in the western United States, like where the Colorado wildfire is burning, has increased over the last thirty years.

Many decades of forest management during which all fires were suppressed has contributed to the problem, as has widespread tree death due to insect damage (which itself may be linked to climate change). But human-driven climate change is also playing a significant role by warming and drying already fire-prone regions as well as by reducing the length of the spring and early summer snow melt season.

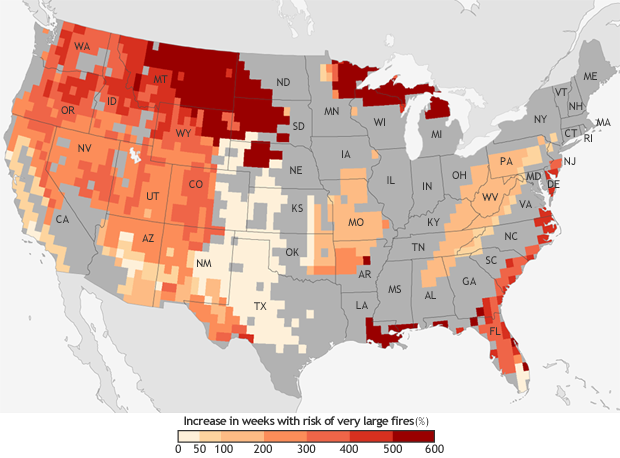

The projected increase in the number of “very large fire" weeks—weeks in which conditions are favorable to the occurrence of very large fires—by mid-century (2041-2070) compared to the recent past (1971-2000). Projections are based on the possible emissions scenario known RCP 8.5, which assumes continued increases in carbon dioxide emissions. NOAA Climate.gov map, based on data from Barbera et al, 2015. More detail.

These trends toward larger fires in the West is very likely to continue into the future thanks to climate change as we continue to emit a high level of greenhouse gases. In recent research looking at trends in weeks where conditions are favorable for very large fires, scientists found that the potential for the development of very large fires is expected to be up to six times as likely by mid-century (2041-2070) compared to 1971-2000. For the Four Corners region, the number of weeks each year where conditions are favorable for the occurrence of very large fires is likely to increase by 200-400%.

These increases in very large, destructive fires have enormous economic and ecological costs.