December in California is normally a time when the wet season kicks into gear. Instead, December 2017 has been marked by a lack of rain, dry vegetation, and gusty, hot Santa Ana winds. These climate conditions have fueled multiple, unseasonably late wildfires across southern California.

Suomi NPP satellite image taken of southern California on December 6, 2017 using the VIIRS instrument. Smoke is visible from various wildfires burning around Los Angeles which had massively grown in size over the previous 48 hours. NOAA Climate.gov image using data provided by the NOAA Environmental Visualization Laboratory.

The largest wildfire is the Thomas wildfire, located northwest of Los Angeles in Ventura County, which ignited during the first week of December. As of December 14, the fire has already burned over 242,000 acres, making it the fourth largest wildfire on record in California and astoundingly the only December-occurring wildfire on the list of California’s twenty largest wildfires. Simply put, fires this big don’t happen this late into the year.

Image taken by the European Space Agencies (ESA) satellite, Sentinel 2 on December 8, 2017. This false color image shows the large burn scar left by the raging Thomas Fire near Ventura, California, north of Los Angeles. Ongoing fires can be seen along the edge of the burn scar in the northern part of the figure. NOAA Climate.gov image based on data from the ESA.

And when large fires burn this close to a sprawling metropolitan city like Los Angeles, destruction is inevitable. The Thomas fire now ranks as the eigth most destructive fire on record after burning over 970 structures to the ground. It still has a long way to go to reach number one, though, as the Tubbs fire in northern California—which we wrote about here—burned over 5,600 structures just two months ago in October.

Smaller but still destructive, the Skirball, Rye and Creek Fires have burned through areas north of Los Angeles in the San Fernando Valley, as well. The Skirball fire formed less than 5 miles from UCLA, which had to cancel classes on December 6.

Difference from normal winds at the 300mb atmospheric level for December 5 - 9, 2017. During the period, a broad high pressure circulation (clockwise rotation of the winds) was present over western North America and an anomalous low pressure circulation (counter clockwise rotation of the winds) was located over the eastern United States. The atmospheric set-up was perfect for creating strong Santa Ana winds over southern California, which fanned the flames of multiple wildfires. NOAA Climate.gov map based on data from NCEP/NCAR Reanalysis data.

How did these fires get so big so fast?

Similar to the recipe list that led to the massive Tubbs fire in October, a “perfect” combination of ingredients came together: extremely dry conditions, plenty of dry vegetation ready to ignite in an instant, and Santa Ana winds roaring down off the coastal mountains. The Santa Ana winds that have spurred the fires to new extremes peak in intensity during early the winter months as cold air settles into the high elevations of the basin and range terrain to the east. Those high pressure systems help move air down the coastal mountains of southern California. Funneled into natural channels as they tumble down the mountains, the winds gather speed. As the elevation drops, the pressure rises, compressing, warming, and drying the winds even further. During the beginning of December, the strongest Santa Ana wind event of the season took place as hot Santa Ana winds were clocked at 70 to 80 mph in the mountains surrounding Los Angeles. The winds helped the burgeoning fires grow thousands of acres in size in the matter of a few hours, forcing the quick evacuation of residents.

Isn’t it the rainy season? What was burning?

California’s rainy season does in fact begin in October, and it normally manages to stave off huge wildfires during Santa Ana months . However, the beginning of the rainy season this year has been an absolute bust in southern California. Los Angeles and San Diego have received only a tiny amount of rain since October 1. And following the normally dry summer months, vegetation—which was especially luxuriant following last winter’s good rains—was primed to burn.

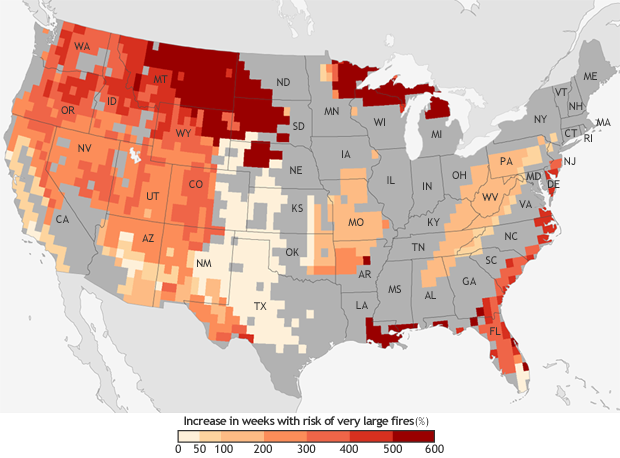

The projected increase in the number of “very large fire" weeks—weeks in which conditions are favorable to the occurrence of very large fires—by mid-century (2041-2070) compared to the recent past (1971-2000). Projections are based on the possible emissions scenario known RCP 8.5, which assumes continued increases in carbon dioxide emissions. NOAA Climate.gov map, based on data from Barbera et al, 2015. More detail.

Climate Change

As noted in previous articles on wildfires across California, according to the U.S. National Climate Assessment, models forecast up to a 74% increase in burned area in California by the end of the century in scenarios with high greenhouse gas emissions.

And in research done in 2015, researchers found that if greenhouse gas emissions remain high by mid-century (2041-2070), there would be a 50 to 100% increase in the number of weeks in the year when climate conditions were favorable for very large fires in southern California as compared to 1971-2000. So being fire-aware will be critical for residents all across the West now and in the future.