Several months in a row of below-average precipitation have brought drought to the Pacific Northwest in spring 2020, with only the northwestern corner of Washington, around Seattle, free of any kind of drought or abnormal dryness as of the May 19 update from the U.S. Drought Monitor. As the region’s dry summer approaches, the winter and spring precipitation deficits pose a threat to livestock operators, farmers, and fish, and heighten the risk of wildfires.

This animation shows drought development across the contiguous U.S. from January-mid-May 2020. Areas of moderate (peach) to severe (orange) drought stretched across much of Washington, Oregon, and Northern California since late March. In isolated parts of north-central and southeastern Oregon, conditions deteriorated to extreme drought (red) as of the May 19 update. Maps from Climate.gov’s Data Snapshots, based on data from the U.S. Drought Monitor.

For many of us, the backdrop of our mental image of Washington and Oregon is the dripping, moss-covered forests of the Coast and Cascade Range Mountains. But a significant portion of each state lies inland of the mountains on a high, dry plateau. Lying in the rain shadow of the mountains, these areas are dominated by public and private rangeland and farms, and their water supply is largely dependent on the mountain snowpack.

When it comes to this winter’s snowpack, says Oregon State Climatologist Larry O’Neill, the concern is less about how little there was and more about how quickly it is melting. Snow totals in several of the state’s mountain ranges, including the North Cascades and the Blue mountains were actually pretty good, and even in the Southeast, where they were below normal, they weren’t record-low. But it is all melting lightning fast.

“Statewide, surface water supplies and streamflows don’t look that bad at the moment, especially because some of the mountain areas have continued to get some rain in the past few weeks,” he explained. “But with the warm temperatures we’ve been having, that snowpack is likely to disappear in a matter of weeks, rather than gradually melting out through June, and those flows are going to crash.”

Once that happens, the foothills and the plateau regions may be facing more serious water shortages. According to the Drought Monitor, when drought reaches “severe” status in Oregon, pastures are often dry, and livestock producers wind up being forced to sell cattle earlier than planned; marshes dry up, impacting waterfowl and other wildlife—including forcing bears into urban areas. In those areas designated extreme drought, the drought is likely to cause planting delays for growers, cut backs in irrigation water, and falling groundwater levels in wells.

In some the state’s most heavily regulated water districts, including the Klamath River district that straddles southern Oregon and Northern California, even the recent rains some parts of the state have experienced may not do much good.

“The picture near the end of April for many areas was really bleak, and that led water managers to slash growers’ allocation for spring planting,” O’Neill explained. In what is essentially a high-altitude desert, all crops depend on irrigation or groundwater supplementation. Faced with extreme cutbacks, many growers simply leave fields fallow. “Even if the surface water outlook improves in late spring, like it has in some places this year, it’s often too late for farmers.”

Farmers can’t just start their planting later; even in a good water year, streamflows decline significantly in summer as the snowpack melts, drawing a firm end to the growing season in the absence of private wells. In a year like this one, where the snowmelt is early and rapid, the season is shorter still.

“This situation is a preview of a challenge that we are probably going to see more often in the next 20 to 30 years, “says O’Neill. Even if winter snowpack doesn’t change significantly as a result of global warming, warmer springs and summers will shift the timing and duration of the melt season, and the runoff will come earlier and be over more quickly. If summer temperatures are hot enough, drought may develop even if precipitation isn’t below average, due solely to extremely high rates of soil moisture evaporation.

Across both Washington and Oregon and down into Northern California, current drought conditions are also elevating fire risk. Already, some private timberlands in western Oregon that normally open to the public for recreation have been closed in anticipation of a bad fire season, according to news reports. In the Southwest corner of the state, the Department of Forestry has started the fire season a month earlier than usual, with all backyard burning prohibited.

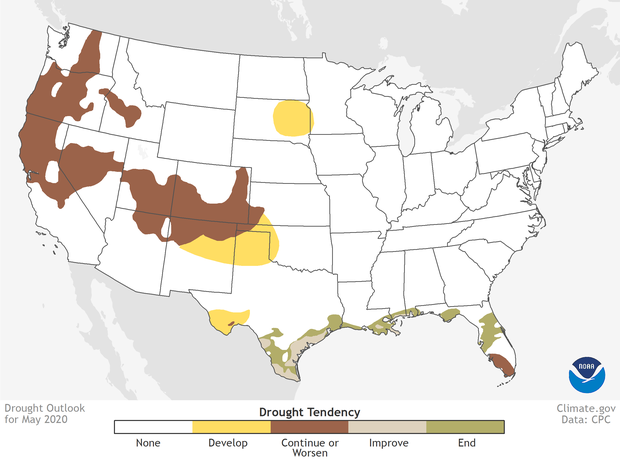

This map shows where drought is expected to develop, worsen, or improve across the contiguous U.S. during May 2020. Map from NOAA Climate.gov Data Snapshots, based on data from the Climate Prediction Center.

Unlike many parts of the East, where it rains all year round, precipitation in much of the West is sharply seasonal, with wet winters that taper off gradually into damp springs. Summers are hot and dry, which means as the year goes on, the chances for significant drought recovery drop. Based on the most recent outlook from the Climate Prediction Center, drought conditions were expected to worsen or persist in May across much of the Pacific Northwest, the Great Basin, and the Four Corners.