Climate & Beer

When you think of wine country in the United States, you probably think of Northern California. And you wouldn’t be surprised to learn that climate has a major influence on grapes, the main ingredient in wine—not to mention a winery’s bottom line. But what region would you consider “beer country”? And how do climate extremes affect some of the key ingredients for making our nation’s most popular alcoholic beverage?

A selection of craft beers. Photo by Flickr user Lauren Topor, via a creative commons license.

Where the hops are

Most of us know that the key ingredient in beer is some kind of fermented grain: that's where the alcohol comes from. But when it comes to all the different tastes and aromas that different kinds of beer have, the hops are just as important. The flower buds of the hops plant are added to the brew to impart bitterness, unique flavors, and aroma to the finished product.

And when it comes to where the hops are, U.S. beer country is the Northwest. According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, 73% of our nation’s hops are grown in the state of Washington, with the remainder roughly split between Oregon and Idaho.

Washington’s primary hops-growing area is the Yakima Valley, located in the Yakima River basin on the eastern (lee) side of the Cascade Mountains. The lower portions of the valley are fairly desert-like, except where the Yakima watershed extends high up into the snowy Cascades. Most of the river runoff is derived from winter precipitation stored as snowpack.

View of the Upper Yakima Canyon in Autumn near Ellensburg, Washington, during the fall season. Photo courtesy of Tom Ring via a creative commons license.

Historically the region produced about 70% alpha (bitter) varieties of hops and 30% aroma types. In an email interview, Ann George, Executive Director of the Washington Hop Commission, said the growing demand for aroma varieties in recent years has completely reversed the acreage mix: in 2015, it was nearly 70% aroma and dual-purpose varieties. Craft breweries like these varieties because they contribute lower levels of alpha (bittering) to beer, but are high in other flavor compounds that contribute unique characteristics (citrus, herbal, floral) to each beer.

The majority of these flavorful varieties have been developed specifically for the Yakima climate, with better heat tolerance than traditional European-style aroma hops. But last summer, Washington’s Yakima Basin—one of the most productive hops-growing regions in the world—saw unusually warm temperatures and intensifying dry conditions. How did the hops stand up to the heat?

A dry, hot streak in Washington

According to the U.S. Drought Monitor, the month of May started out with moderate to severe drought conditions in the Yakima Basin. By mid-July, 100% of Washington was facing severe drought conditions, and nearly a month later, the entire western half of the state was designated under the extreme drought category.

The entire growing season had also been unusually warm. The months of April-September were record warm for Washington, and the average summer temperature beat the state’s previous record set in 1958. Extremely dry and hot conditions persisted in the Yakima Basin through the harvest season, which extends from late August through early October, depending on the variety.

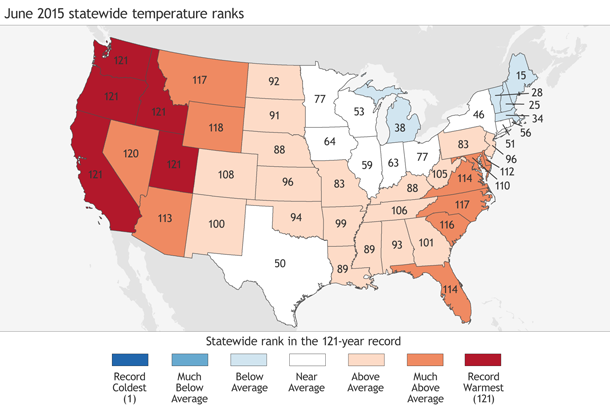

Statewide temperature ranks for June 2015 within the historical record (1895-2015), from record coldest (darkest blue) to record warmest (darkest red). Washington was one of several states in the western U.S. that saw its record warmest month on record. Map adapted from analysis by National Climatic Data Center.

Heading into harvest season in August 2015, the USDA National Agricultural Statistics Service reported that production in Idaho, Oregon, and Washington was forecast at 80.0 million pounds for 2015, up 13% from 2014’s 71.0 million pounds. Washington itself was forecast to produce 57.9 million pounds. But yields in over-heated Washington were forecast at 1,800 pounds per acre, down from 1,936 pounds in 2014. According to the report, “yields for Alpha varieties were reported to be above average, while high temperatures in June and July across the Pacific Northwest negatively impacted the yield of aroma varieties.”

So did Washington manage to deliver despite these challenges? The year-end USDA national hop report released on December 17 found that some aroma varieties, such as Willamette and Centennial, did yield poorly. “Early season aroma varieties, particularly European noble types, were most impacted by the extreme heat during the latter half of June, as bloom was underway,” George reported. But overall, Washington still had its highest number of acres harvested on record going back to 1915, producing 75% of the nation’s crop at 59.4 million pounds.

These images show the progression of Galena hops growing in the heart of hop country in Moxee, WA. From left to right, the images show the hops’ status on week 28, week 33, and, finally, on week 36, right before harvest. By this point, the natural oils have accumulated and the aroma is strong. Photo credit: Hop Growers of America.

As far as the drought and water concerns, George said most growers were able to adapt using groundwater supplies and other sources. “Growers on the Roza Irrigation District were generally able to secure additional water supplies or idle a portion of their land to concentrate tight supplies on their higher value crops,” she said. “Most of the adverse impacts to yield were seen on the Wapato Irrigation Project, where antiquated delivery systems left some growers with inadequate water.”

Yakima Valley hops growers generally managed to beat the 2015 summer heat. The future, however, looks likely to include a lot more years like 2015. Corresponding via email, Guillaume Mauger, a research scientist with the University of Washington’s Climate Impacts Group, said that climate models project the unusual warmth of 2015 will be the “new normal” in the decades following the middle of this century.

Precipitation, on the other hand, is not projected to change: "On an annual and seasonal basis, total precipitation is not projected to change by much—year-to-year natural variability will continue to dominate through to the end of the 21st century. This means that the primary consequence of climate change for summer water supply will be felt via reductions in winter snowpack, and corresponding reductions in spring/summer melt,” he said.

A 2010 paper by Mauger’s colleague, Julie Vano at Oregon State University, quantified the impact of climate change on water restrictions for junior water users in the Yakima basin. Her results were summarized in a report prepared by the Climate Impacts Group in 2013:

In the Yakima basin, for example, water shortage years—years with curtailed water delivery to junior water rights holders—are projected to increase from 14% of years historically (1979-1999) to 43 to 68% of years by the 2080s (2070–2099) for a low and a medium greenhouse gas scenario, respectively.

Ugh! Tastes like drought.

The availability of certain varieties of hops is not the only way climate can affect the taste of beer. Drought conditions along the U.S. West Coast are also brewing up potential problems for beer producers. In Northern California, craft breweries draw water from California’s Russian River—a 110-mile long artery that winds through Sonoma and Mendocino counties. This region has been incredibly dry over the last four years; as we reported back in September, every region in California was missing at least a year’s worth of precipitation.

In the face of this historic drought, the Sonoma County Water Agency (SCWA) is working to secure future water supply for more than 600,000 people in portions of Sonoma and Marin counties. Dry conditions this past spring called for restricted outdoor water use and a reduction in the amount of water released from the Lake Mendocino reservoir into the Russian River. According to the agency, reduced river flows were expected to preserve the equivalent of 10% of Lake Mendocino’s current water supply storage, or 6,300 acre-feet of water.

In an article published in February 2014, interviews with staff at local breweries highlighted some of the potential downsides of having to rely more heavily on groundwater due to restricted river water supplies. Mineral-heavy groundwater supplies can sometimes affect the taste of the beer, and not in a good way—one spokesperson referred to it as “like brewing with Alka-Seltzer.”

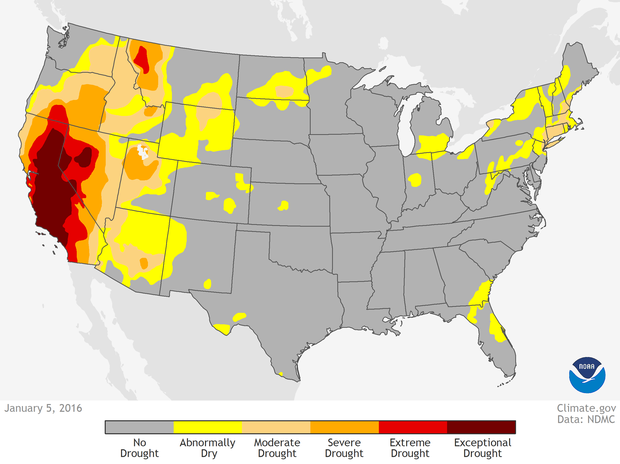

Map of drought conditions in the United States as of January 5, 2016. Severe to exceptional drought still covered California. Map courtesy Data Snapshots.

While the region is still officially in drought conditions, according to SCWA spokesperson Ann DuBay, water storage levels are much better than they were in 2014, thanks to a couple of larger storms in December 2014 and March 2015. As of November, Lake Mendocino held about 28,500 acre-feet of water, which is a little more than half of its target water supply storage. Lake Mendocino had about the same water levels in February 2014 as it did in November 2015, but the timing makes a huge difference: in November, Sonoma County was heading into its rainy season. February is toward the end of the rainy season.

California receives the vast majority of its rainfall in the winter months. In the past, the connection between wet winters and El Niño has been less reliable in the northern part of the state than the southern part. However, according to an analysis by the NOAA Drought Task Force, the odds for a wet winter across the entire state improve the stronger the El Niño event is, and the 2015-16 event is currently forecast to remain strong through winter.

As of January 11, Lake Mendocino held 44,490 acre-feet of water, about 69.3% of its target water supply, right as El Niño began to deliver a series of storms to Northern California early in the New Year.

Looking Forward

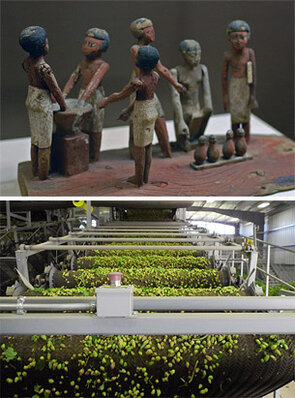

(Top) An Egyptian wooden model of beer making in ancient Egypt on display at a museum in San Jose, California. Photo credit: E. Michael Smith, Wikipedia. (Bottom) The modern way: After hops are separated from the vine, they go through a gravity-driven filtering process, separating hops from leaves. Photo credit: Hop Growers of America.

While we can definitely cheer the raised odds for rain on the West Coast, drought continues to cause problems for hop production elsewhere. According to George, much of Europe experienced a substantial crop loss in 2015 due to drought, with German hop production down 26% from last year. Germany and the U.S. are the two biggest hop-producing countries in the world, each contributing about one-third of global production.

Changing climate conditions also have the potential to alter traditional beer brewing practices that have been passed down through generations. Take, for instance, the case of a brewmaster in Belgium who has seen the timing of his annual brewing period shift markedly since his great grandfather founded the brewery in 1900.

In 2015, a number of leading breweries signed a ‘climate declaration’ to call attention to the specific risks and opportunities of climate change on the beer industry. “Warmer temperatures and extreme weather events are harming the production of hops, a critical ingredient of beer that grows primarily in the Pacific Northwest,” reads the declaration. “Rising demand and lower yields have driven the price of hops up by more than 250% over the past decade. Clean water resources, another key ingredient, are also becoming scarcer in the West as a result of climate-related droughts and reduced snow pack.”

The declaration also lists examples of how breweries are taking action to reduce their own environmental impact and tackle climate change, such as measuring greenhouse gas emissions and using renewable energy sources. By anticipating future changes and helping ensure their businesses remains resilient, brewers can ensure that beer lovers around the globe stay hoppy happy.

References

Climatological Rankings. NOAA National Centers for Environment Information – Climate.

Hops Report. USDA National Agricultural Statistics Service. 10 July 2015.

Hops Report. USDA National Agricultural Statistics Service. 12 August 2015.

Hops Report. USDA National Agricultural Statistics Service. 17 December 2015.

Snover, A.K, G.S. Mauger, L.C. Whitely Binder, M. Krosby, and I. Tohver. 2013. Climate

Change Impacts and Adaptation in Washington State: Technical Summaries for Decision

Makers. State of Knowledge Report prepared for the Washington State Department of Ecology.

Climate Impacts Group, University of Washington, Seattle.

Vano, J.A. et al., 2010. Climate change impacts on water management and irrigated agriculture in the Yakima River Basin, Washington, USA. Climatic Change 102(1-2): 287-317.

What can drought-stricken California expect from the forecast El Niño winter? NOAA Drought Task Force. August 2015.

Related Links

Drought and Hot Weather Cause Trouble for Hops Growers. CNBC.com. 24 Jul 2015.

Statement from Sonoma County Water Agency General Manager Grant Davis on State Water Board Vote to Toughen Water Restrictions. Sonoma County Water Agency. 17 March 2015.

Reduced Russian River Flows Approved by State Water Resources Control Board. Sonoma County Water Agency. 1 May 2015.

California Brewers Fear Drought Could Leave Bad Taste in Your Beer. NPR. 20 February 2014.

Climate Change Blamed for Putting Belgium Beer Business At Risk. The Guardian. 3 November 2015.

Beer Companies Join Call for Action on Climate Change. Ceres. 10 March 2015.

Resources

USAHops.org