2014 State of the Climate: River Outflow

Why river outflow matters

When the amount of water flowing through a river channel is low, it can reduce public and agricultural water supplies, threaten the health of river life, and disrupt shipping and transportation operations. Periodic flooding has ecological benefits in some watersheds, but when high flows push rivers over their banks, the flooding can also ruin crops, damage infrastructure, and degrade water quality. As part of the State of the Climate series of reports, scientists keep track of the flow at the mouths of rivers, where they empty into larger rivers or the sea.

Conditions in 2014

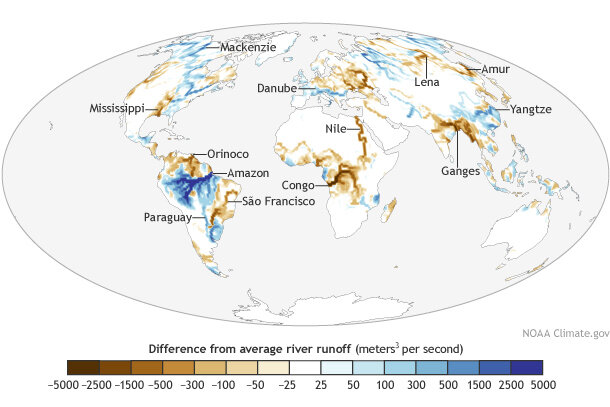

River outflow in 2014 compared to the 1979-2013 average. Adapted from Plate 2.1o in State of the Climate in 2014. Download editable PDF version.

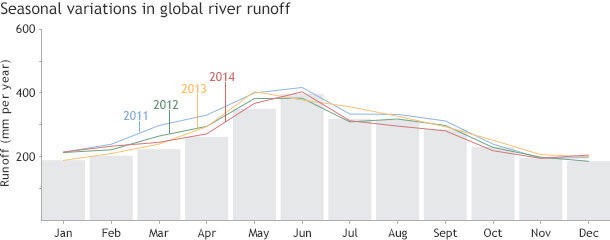

Adapted from the State of the Climate in 2014 report, the map shows locations where 2014 river outflows were below (color) or above (color) the 1979-2013 average. Overall, average global outflow in 2014 slightly exceeded the climate normal. Global average flow hit a relatively high peak in Northern Hemisphere spring before falling in the summer.

Seasonal variations in global river runoff over the last four years (colored lines) compared to the 57-year climatological average for each month (gray bars). Adapted from Figure 2.20 in State of the Climate in 2014.

South America had significantly high outflow in the early months of 2014, although overall flow varied across the continent’s river systems, largely reflecting precipitation and other global hydrological patterns in 2014. The Amazon and Paraguay Rivers experienced a high-flow year but the Orinoco, Tocantins, and Sao Francisco Rivers experienced a low-flow year. Europe also had higher than usual flow early in the year.

Overall, however, there was a large decrease in the spring’s high-flow season compared to 2013. Most rivers showed lower than usual conditions except for a few rivers near the Mediterranean Sea such as the Danube. Asia experienced a considerable low-flow deficit in August. The Ganges–Brahmaputra, northern Indochina peninsula, Lena, and East Asia were in a low-flow state, while the Kolyma, Ob, and river systems in southwestern China were in a high-flow state.

North America, Africa, and Australia experienced an average year in terms of annual amount and seasonal variations of runoff, though the peak occurred one month earlier than the long-term average in Australia. Rivers in the northern part of North America such as the Yukon and the Mackenzie experienced high flow, while rivers in the southern part of North America (including the Mississippi and the Colorado) and in Africa (the Congo and the Nile) had lower flow than their long-term average.

Change over time

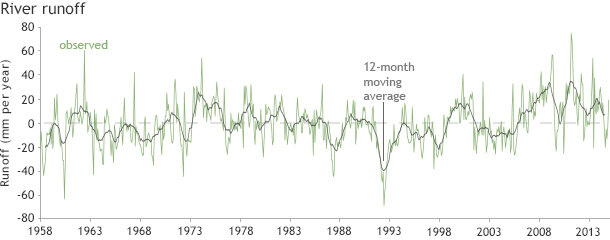

Since records began in 1958, global river outflow has experienced extended periods of both high and low phases. The graph shows that 2014 maintained the trend of overall high river flow that began in 2005.

Annual river outflow since 1958 compared to the 12-month moving average. Adapted from Figure 2.20 in State of the Climate in 2014.

The Fifth Assessment of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change concluded that over the long term, runoff and river discharge have generally increased at high latitudes, with some exceptions. However, the report concluded, “no long term trend in discharge was reported for the world’s major rivers on a global scale.”

References

H. Kim and T. Oki, 2015: [Hydrological cycle] River discharge [in “State of Climate in 2014”]. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society (BAMS), 96 (7), S26-27.

IPCC, 2013: Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Stocker, T.F., D. Qin, G.-K. Plattner, M. Tignor, S.K. Allen, J. Boschung, A. Nauels, Y. Xia, V. Bex and P.M. Midgley (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, 1535 pp, doi:10.1017/CBO9781107415324.