June 2016 ENSO discussion: The new neutral

We’re sticking a fork in this El Niño and calling it done. After spending more than a year above average, sea surface temperatures in the central and eastern equatorial Pacific had mostly returned to near average by the end of May. Forecasters don’t think we’ll remain in neutral territory for long, though. There’s an approximately 65% chance that sea surface temperatures will drop into the La Niña realm (more than 0.5 degrees below normal) by the July – September period. This chance increases to around 75% by the fall.

I’ll get into what’s behind these numbers in a bit, but first, let’s bid a fond farewell to the big 2015-2016 El Niño.

The king is dead!

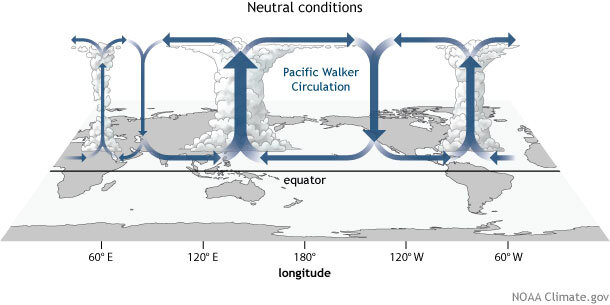

As we’ve reiterated many times in this blog, the El Niño/La Niña (ENSO) cycle is characterized by the changes in tropical Pacific temperatures and the corresponding response of the atmosphere. During El Niño, atmospheric changes include weaker trade winds and upper-level winds, more convection and rainfall in the central or eastern Pacific, and drier conditions over the far western Pacific and Indonesia. Over the past few months, the tropical Pacific has cooled off rapidly, and all these atmospheric indicators returned to average conditions during May.

Generalized Walker Circulation (December-February) during ENSO-neutral conditions. Convection associated with rising branches of the Walker Circulation is found over the Maritime continent, northern South America, and eastern Africa. NOAA Climate.gov drawing by Fiona Martin.

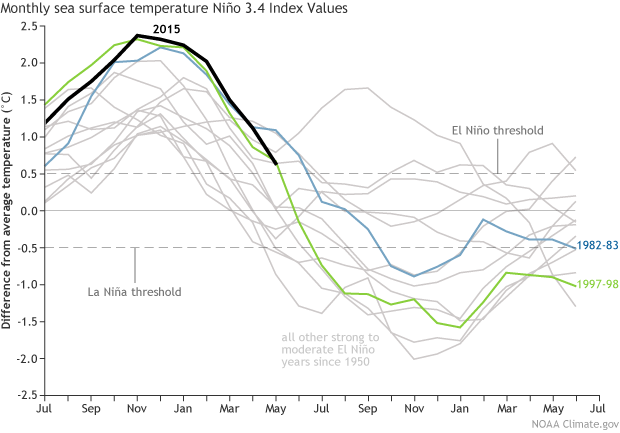

This El Niño was often compared to the 1997/98 event, because the ocean temperatures in the key Niño3.4 region in the Pacific followed a similar progression, and the peak departure from normal in the 3-month-average was the same: 2.3°C (4.1°F) above normal. However, this event differed from that one in a lot of ways, including the impact on United States precipitation during the winter.

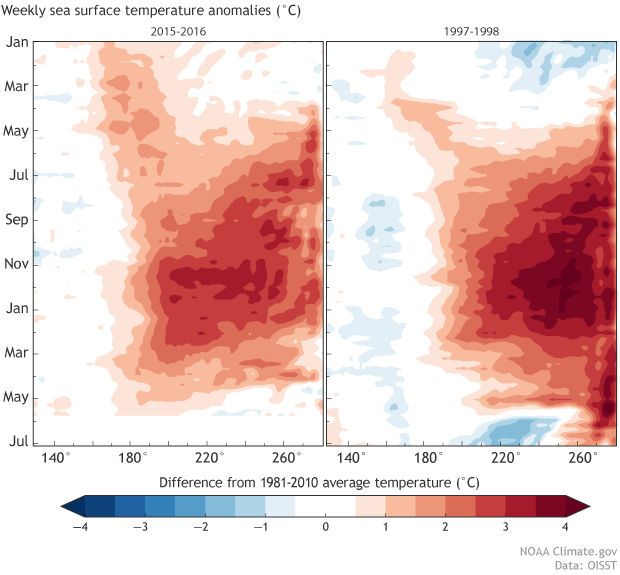

Equatorial Pacific sea surface temperature, 2015-2016 (left) compared to 1997-1998 (right). Each row in this type of image is the departure from average at that time. Weekly data is shown starting in January 2015 and 1997 (top). Data ends at the end of May 2016 (left) and end of June 1998 (right). Climate.gov figure from CPC data.

For one thing, there was more ocean surface warming in the western Pacific and less warming in the eastern Pacific during 2015/16 than 1997/98. Also, the amount of warm water under the surface was less during 2015/16 than 1997/98. (If you want to compare all kinds of information about the ocean during the two events, you can check out the Ocean Reanalysis Comparison site.) The atmospheric response during 2015/16 was also generally weaker than during 1997/98.

In short, as you’ve heard many times on this blog, no two El Niños are alike.

Why am I reviewing all this? Because we don’t expect the rest of 2016 to look exactly like 1998 did, either, even though ocean temperatures in the Niño3.4 region have followed a very similar decline. Just looking at one number (the Niño3.4 index) can give an incomplete picture of the evolution of ENSO events. Even though our forecasts are projections for Niño3.4 ocean temperatures, forecasters take a number of current conditions into consideration. In other words, if La Niña develops this fall, don’t expect it to develop just like the one following the 1997/98 event.

Monthly sea surface temperature in the Niño 3.4 region of the tropical Pacific compared to the long-term average for all moderate-to-strong El Niño years since 1950, showing how 2015/16 (black line) compares to other events. Climate.gov graph based on ERSSTv4 temperature data.

Long live the queen!

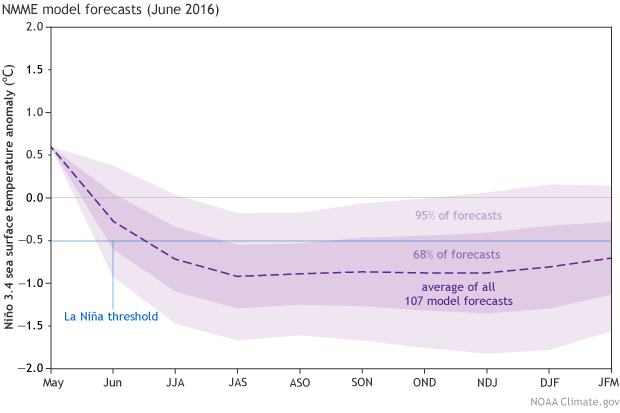

Both human forecasters and computers are reasonably confident (75% chance) that sea surface temperatures will cross the La Niña threshold by the winter. However, there’s a fair bit of uncertainty still about how the La Niña would progress, and forecasters are currently favoring a weak or borderline moderate event.

This spring, the amount of cooler water under the surface of the tropical Pacific is substantial, and it’s been rising up to the surface. This is a source of confidence that sea surface temperature anomalies will continue to cool through the summer.

Dynamical models (large computer simulations that use atmospheric and ocean physics to make predictions) predict that Niño3.4 temperatures will cross the La Niña threshold soon. They don’t, however, foresee a continued steep cooling. Most forecasts from the North American Multi-Model Ensemble are in the region of about -1.25° to -0.5° below normal through the Northern Hemisphere winter.

Climate model forecasts for the Niño3.4 Index, from the North American Multi-Model Ensemble (NMME). Darker purple envelope shows the range of 68% of all model forecasts; lighter purple shows the range of 95% of all model forecasts. NOAA Climate.gov image from CPC data.

Just like it did with El Niño, the atmospheric response to the changed sea surface temperatures should reinforce La Niña. La Niña is characterized by a stronger Walker Circulation, where warm air rises in the far western Pacific/Indonesia, heads eastward at upper levels, descends to the surface over the eastern Pacific, and blows toward the west as the trade winds. Stronger trade winds cool the surface and keep the warmer waters pooled in the western Pacific. Over the summer, we’ll watch this response carefully, for clues about how La Niña might evolve and potentially influence the 2016/17 winter climate.

La Niña’s effect on U.S. summer climate is limited, although it can influence hurricane seasons. NOAA’s official outlooks for the Atlantic and Eastern Pacific hurricane indicate that near-normal seasons are most likely in both. A major source of uncertainty in this outlook is the rate at which La Niña may develop and intensify. Check out Tom's recent post and the official outlooks, especially the "Reasoning behind the outlook" sections, for more detail on how climate factors, including La Niña, can influence the growth of hurricanes.

Comments

MJO and ENSO base state

RE: MJO and ENSO base state

No, there has not been a blog on that subject on this site. We had a blog a while back on the MJO in general, and how it can interact with the ENSO state: https://www.climate.gov/news-features/blogs/enso/what-mjo-and-why-do-we…

In any given week, the MJO phase always has some effect on ENSO, either promoting an event, counteracting it, or having a neutral influence. When an El Nino gets as strong as this one did, the MJO influence may not be easy to note during the peak months. It is easiest to see during the development phase in spring and early summer. Maybe a blog about its effect on the 2015-16 El Nino is not a bad idea.

RE: RE: MJO and ENSO base state

Thank you for the post.

RE: Thank you for the post.

It is hard to make a definitive attribution on the cause of the recent above normal rainfall in Malaysia. However, the sea surface temperature (SST) in the northeastern Indian Ocean, including the vicinity of Malasia and southeast Asia, has been above average. This can produce above average atmospheric water vapor, leading to rainfall in the region. Why has the SST been above average? Above average SST in at least the east side of the region, including Indonesia and the western tropical Pacific Ocean, often develops in association with La Nina, and below average SST often develops in association with El Nino. During this strong El Nino that just ended, below average SST did not appear. And since La Nina is not present yet right now (although it is favored to develop in the next few months), we cannot say that the above average SST is due to La Nina. So ENSO may not be playing much of a role here. Upward trends in SST in the region have been noted, possibly in association with long-term climate change. But this is just an idea, or a possibility. If it is true, it would imply that Malaysia can expect more rain in the long term. But we are only speculating.

RE Increased rainfall

Effects of the 2015-16 El Niño

RE: Effects of the 2015-16 El Niño

As previously mentioned, we're currently putting together a manuscript that will provide an overall retrospective of the 2015-16 event. If that paper is accepted and released, we'll put a note somewhere on the blog about its availability.

RE: Effects of the 2015-16 El Niño

Less in Neutral and more in El Niño and La Niña?

RE: Less in Neutral and more in El Niño and La Niña?

I don't believe that there have been any documented changes in the frequency of El Nino and La Nina compared to neutral. It's certainly not uncommon for an El Nino to rapidly transition to La NIna (i.e. 72/73 to 73/74 and 97/98 to 98/99).

Model for ENSO

La Nina summer midwest high pressure dome?

RE: La Nina summer midwest high pressure dome?

While the current seasonal outlooks do favor above average temperatures across much of the United States during the summer, there is no tilt in the odds toward below average preciptation in the Midwest this summer. The drought outlook indicates drought developing in parts of the northern Plains, but not in the Midwest.

The Blob

RE: The Blob

The trade winds usually refer to the winds closer to the equator. The large-scale winds that affect California (leaving aside microclimates, like land-air breezes) are just simply "the westerlies." El Nino tends to shift the westerlies/jet stream southward. La Nina does the opposite. Obviously we didn't see much of a southward shift this past winter, which is why northern CA/Pacific NW got doused and southern CA remained dry. ENSO tends have its most significant impacts during the Northern Hemisphere winter/early spring, so any potential impact now is probably rather small and what you are seeing may have no known cause.

SSW Polar Vortex

Effects of the 2015-2016 el nino

Add new comment