July 2022 La Niña update: comic timing

I’m in San Diego this week, gazing out across the Pacific toward La Niña’s cool tropical ocean surface. (I’m not here for Comic-Con, but there are a lot of posters around the city that keep that upcoming event in the forefront.) Just over my horizon, La Niña—the cool phase of the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (“ENSO” for short)—remains in force, despite some warming in the sea surface temperature over the past month or so. Forecasters expect La Niña to continue through the summer and into the fall and early winter.

Sea surface temperatures around the equator in the central and eastern Pacific were mostly cooler than average (blue) in June 2022. A few warm pockets (orange) dotted the far eastern Pacific. NOAA Climate.gov map from our Data Snapshots collection.

Ka-Pow!

Numbers-wise, there’s about a 60% chance of La Niña through the summer, ticking up a bit to the mid 60%s around 66% by October–December 2022. The second most likely outcome is ENSO-neutral conditions. El Niño is a distant third, with chances only in the low single digits through the early winter. This forecast isn’t much different from the past couple of months.

The official CPC/IRI ENSO probability forecast. The bars show the seasonal chances for each possible ENSO state—El Niño (red), La Niña (blue), and neutral (gray)—from spring 2022 through winter 2022–23. The forecast is based on a consensus of CPC and IRI forecasters, and it is updated during the first half of the month, in association with the official CPC/IRI ENSO Diagnostic Discussion. It is based on observational and predictive information from early in the month and from the previous month. Image from IRI.

While we’re doing the numbers, let’s see how La Niña measured up last month. As I mentioned above, the cool sea surface temperature anomaly weakened a bit in June, but remained in La Niña territory. (Anomaly = difference from the long-term average, long-term being 1991–2020 here, and the La Niña threshold is -0.5 °Celsius, which is just shy of 1 degree Fahrenheit.) According to the ERSSTv5, our most consistent sea surface temperature dataset, June’s sea surface temperature anomaly in the Niño-3.4 region was -0.8 °C. This is the 7th-strongest negative June anomaly in our 1950–present record.

Three-year history of sea surface temperatures in the Niño-3.4 region of the tropical Pacific for 8 previous double-dip La Niña events. The color of the line shows the ENSO state in the third winter (red: El Niño, darker blue: La Niña, lighter blue: neutral). The black line shows the current event. Monthly Niño-3.4 index is from CPC using ERSSTv5. Time series comparison was created by Michelle L’Heureux, and modified by Climate.gov.

This recent weakening in the Niño-3.4 anomaly—it was -1.1 °C in May—is partly due to a slight diminishment of the trade winds, the prevailing east-to-west winds near the Equator, in the first half of June. When the trade winds weaken, wind-driven evaporative cooling slows and the surface warms. Also, a fairly weak downwelling Kelvin wave, a region of warmer-than-average water under the surface, has been moving from west to east over the past few months , gradually rising toward the surface.

The trade winds re-strengthened over the second half of June, and remain stronger than average as we go to press. This will likely help to cool the surface, and may contribute to an upwelling Kelvin wave, a region of cooler-than-average subsurface water that moves west to east. Along with being a sign that La Niña’s amped-up Walker circulation—the atmospheric response to La Niña’s cooler sea surface—is still present, the stronger trades are a source of confidence in the forecast for La Niña to continue through the summer.

Sea surface temperatures the week of July 9, 2022, showing the warm-to-cool gradient in temperatures across the tropical Pacific Ocean from west to east. Temperatures in the West Pacific Warm Pool, around the Maritime Continent, are above 80 degrees Fahrenheit (yellow-orange), while a cooler tongue of water (blue) extends from the coast of South America to the central Pacific. The prevailing east-to-west trade winds near the equator create this temperature contrast by pushing warm water west and allowing deeper, cooler water to well up to the surface. NOAA Climate.gov image from our Data Snapshots collection.

Zowie!

That said, there may well be short-term fluctuations in the Niño-3.4-region sea surface temperature that flirt with the La Niña threshold. For example, the current weekly Niño-3.4 index is -0.5°C. (This uses a different sea surface temperature monitoring dataset, the OISST.) However, as Michelle detailed a few years ago, ENSO is a seasonal phenomenon, meaning we evaluate it using monthly and seasonal averages, not weekly. Most climate models are predicting that the three-month-average Niño-3.4 index will remain below -0.5°C, another source of confidence in the forecast.

Thwack!

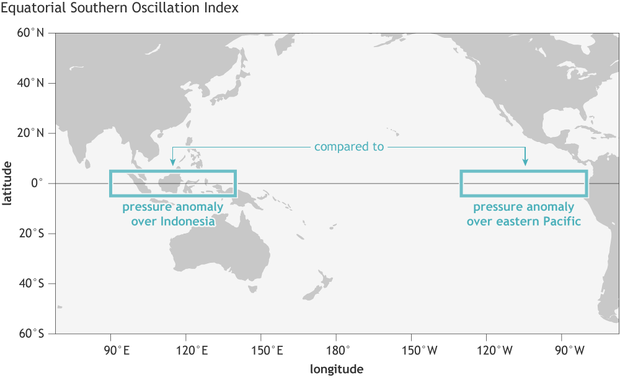

As I mentioned above, the June sea surface temperature anomaly was the 7th-most negative June anomaly on record. Where does the atmospheric response rank? Let’s take a look at the Equatorial Southern Oscillation Index (EQSOI), an index that measures the relative atmospheric surface pressure in the equatorial eastern Pacific versus that in the western Pacific.

The Equatorial Southern Oscillation Index compares pressure anomalies across a broad region of the eastern tropical Pacific (5 degrees North and South latitude, 80–130 degrees West longitude) to pressure anomalies on the other side of the basin (5 degrees North and South latitude, 90–140 degrees East longitude). NOAA Climate.gov image by Fiona Martin.

When this index is positive, it means the pressure is relatively higher in the east and lower in the west, indicating a stronger Walker circulation. June 2022 tied for third strongest on record (1950–present), which got me wondering about the relationship between the strength of the Walker circulation in the summer to the Niño-3.4 index in the following early winter.

It turns out that the June EQSOI has a correlation of about 0.7 with the Niño-3.4 index in the following November–January period. This is a fairly strong correlation, but by no means does it guarantee any particular November-January outcome. The other tied-for-third June, 2013, was followed by an ENSO-neutral winter. Most other Junes in the range of the 2022 value were followed by La Niña winters, though.

Each dot on this scatterplot shows the atmospheric ENSO conditions each June (horizontal axis) since 1950 versus the oceanic ENSO conditions the following November–January (vertical axis). When the June Equatorial Southern Oscillation Index (ESOI) is negative, winter Oceanic Niño Index conditions are frequently in the El Niño range (red dots), sometimes neutral (gray dots), but rarely in the La Niña range (blue dots). When June ESOI is positive, the winter is usually in the La Niña range, sometimes in the neutral range, but rarely in the El Niño range. The June 2022 EQSOI—shown as an open circle on the horizontal axis—was the third-highest June SOI on record. Data from CPC, image by Climate.gov.

Blammo!

Given all these sources of confidence, why isn’t the probability of La Niña higher? First, while a majority of the climate models do predict continued La Niña, there is still a pretty wide range of potential outcomes. Also, as I mentioned above, the subsurface temperature in the eastern half of the tropical Pacific is a bit warmer than average. If this anomaly is large—much cooler than average, or much warmer—it has a stronger relationship with the eventual Niño-3.4 index. However, when it is pretty small, as it was in June 2022, the outcomes are more varied. Finally, as we’ve covered extensively, a triple-dip (three-peat!) La Niña is a pretty unusual occurrence.

That’s all, folks! I’m going to go dip my toes in the Pacific.

Comments

la Nina

It sure does look like the cold water pool south of the equator is warming and breaking up and thankfully after January this looks like La Nina's last hurrah. If the long term models bear out the waters in the equator will start to have a positive anomaly. I think we are due for a strong El Nino in the next couple of years,

La Nina

To be fair, it looked like La Nina was expiring this time last year. The data is presented right in this blog!

Current ENSO data is suggestive of a different kind of pattern that does not seem to be following a "cookie cutter" level of predictability. La Nina is still firmly going until further ado.

La Nina

The way things look I am putting my money on La Nina gone by February. Things this year are much different than they were last season.

Weather

I'd definitely take " El Nino " any time over "La Nina" we are running out of water because of "La Nina" SHE NEEDS TO GO.

About comments

Just a reminder...

Nino 3.4 Discrepancy - La Nina Over?

It's very interesting to point out while La Nina is still hanging on, the Australian counterpart has declared La Nina over even though their La Nina Watch criteria has been met for a possible re-forming later this year.

The recent Bureau of Meteorology shows that the recent Nino 3.4 index they've registered is -0.3°C, with the month of June being -0.4°C, which actually falls below the -0.5°C threshold (-0.8°C on their side) of La Nina and is in ENSO-neutral phase. Are they seeing numbers that they're looking at that you're not seeing and could be a discrepancy?

I'm also curious if La Nina is declared over on your side let's say next month but La Nina impacts still remain possible like the SOI being very positive among other things (date line cloudiness), would you still declare a La Nina Watch even if the final advisory happens? And I'm also wondering if that has ever happened before in the past for both La Nina and El Nino?

Hi Graig, I don't believe…

Hi Graig,

I don't believe they are seeing any numbers differently than we are. Different groups simply use different datasets on different time scales to look at different thresholds. And that is where any discrepancy might arise.

I'll have to look back at past La Nina Watches but it is not unfathomable to imagine a scenario where we end a La Nina one month but then put out a La Nina watch for possible La Nina conditions within the next 6 months. Rare, of course, but not out of the realm of possibility.

El Niño is a big problem for Wisconsin

El Niño is not good for snowy winters for Wisconsin I am praying La Niña is happing again for 3rd straight winter because El Niño is mean it needs to die forever why does everyone hate La Niña get over it La Niña is not bad it helps cools the planets: El Niño is very bad for the planets it causes warmer years for the earth that is unwelcome for me

El Nino

We are in out third season of a brutal drought. La Nina has been really bad for California the past couple of years. El Ninos are favorable for CA more often then not. We are due

El Niño

La Niña is extremely bad for the southwest. Drought continues to dominate the south and west during La Niña. During La Niña winters are drier than normal. Remember that the west coast unlike the rest of the US, does not get summer thunderstorm's. All the rain falls just during winter.

Southwest monsoon

The conviction that La Niña conditions are hostile to monsoonal thunderstorms is being disproven on a daily basis. I am curious as to the impact the ENSO has upon the Atlantic High. This summer has seen unusually large and strong effects, suppressing TS activity in the Atlantic basin as the High has reached effects to the western Gulf, sending extra moisture to the Southwest. Meanwhile rainfall totals in Florida are down significantly. How are these effects connected, and is this becoming a sort of “stable 2” condition as the climate changes?

North American monsoon and Atlantic effects

Emily discussed the relationship between La Nina and the North American monsoon in her latest post. The relationship does not appear to be strong, though there is some research that suggests there could be some connection. Therefore, there does not seem to be a basis that La Nina is hostile to monsoonal thunderstorms, though it may not be particularly favorable either.

Regarding the North Atlantic high, La Nina is associated with a strengthened high, but it also tends to bring reduced wind shear and increased Atlantic tropical cyclone activity. Therefore, the quiet Atlantic season so far (though that can change quickly!) is not typical for La Nina. Therefore, the reasons for the particular nature of this year's Atlantic high and climate variability in general are not immediately clear to me.

ENSO and the Atlantic High

Thank you for that reply. There certainly seem to be a persistent anomalous condition in the Atlantic basin and, subjectively, rainfall locally (Central Florida) is less than 50% or our normal summer monsoon, which provides the bulk of our annual rainfall. We’ve never experienced less rain than Arizona before.

Sept North Atlantic TRS

The tropical waters of the North Atlantic are high and conducive for TRS formation.

September looks on the cards for hurricane formation and an end to the droughts in Europe.

who will win El Nina or El Niño.

You’re kidding right? The…

You’re kidding right? The southwestern U.S. is on fire and partially because of La Niña. The drought around here is extreme. I’m praying for El Niño every day!

Weather

You forgot to mention La Nina causes extreme droughts, we are running out of water because of La Nina, so you are Right, we don't like la Nina because of its influence on rain patterns causing devastating droughts worldwide, I will rather have warmer weather with lots of rain than cooler weather with NO WATER, I'm praying La Nina DIES sooner rather than later.

Big problem for Wisconsin

La Nina is a problem in the Western US, CA in particular, but the entire region. Until their recent deluge, TX was a victim of a long-running drought that forced tremendous losses on ranchers and farmers. When you see reports of extreme drought, forest fires, etc. in the West, that's in large part the work of La Nina.

Red Tide

Can you give any thought to a correlation between 2nd year of La Nina and the significant volume of the red tide we are experiencing on the Nicoya Peninsula in Costa Rica? We have been inundated with red tide since the middle of January and have had very few days without it.

I am by no means a red-tide…

I am by no means a red-tide expert, let alone a red-tide expert for Central America. But I can imagine a situation where La Nina impacts coastal currents/ocean dynamics in a way that either helps or hurts the development of red tide.

I'd have to search the literature, though, to see if there are any clear connections, and if anyone has looked at double dip La Ninas. The issue of course is that there have not been that many double dip la ninas which makes conclusions hard to draw on their influence.

La Niña

Interesting post which builds on what Michelle wrote a few years ago about the demise of El Niño and La Niña. So, thanks Emily.

EQSOI and Nino3.4 index

Very interesting blog on the current ENSO conditions.

As we know the EQSOI is the response to sea surface temperature difference (east and west) in the tropical Pacific. Then, how can June EQSOI be relate to the Niño-3.4 index in the following November–January period?

The figure caption for EQSOI should be "eastern tropical Pacific (5 degrees North and South latitude, 80–130 degrees West longitude)" instead of "western tropical pacific". Just a minor typo may be.

Nice catch on the typo! As…

Nice catch on the typo!

As for the connection, we know correlation does not mean causation but it could reflect the broader of evolution of a developing La Nina which tends to peak in strength closer to the Northern Hemisphere winter.

A little help for a layman

I'm sorry, I don't understand half of this data. I'm here because my weather man says the persistent heat domes sitting over the top of us are because of La Nina. We're reaching temps of 114 heat index in Illinois with high humidity and no wind (the lack of wind and the ridiculously high heat index daily is really odd for us), so I'm trying to find out when this thing will stop it and these heat domes will move off. I have chickens who can't tolerate this heat and I'm desperate to keep them safe, and this weather is just horrific.

Hi Stacey, I'm not sure that…

Hi Stacey,

I'm not sure that I'd blame the current heatwaves on La Nina. (though it certainly is very very hot in many places). La Nina tends to have its biggest impacts during the winter. With that said, there is a slight relationship between La Nina and warmer temperatures in the central Plains during Summer.

The long and short of it is that even though La Nina is favored to last through Winter, I don't think it is the leading reason for this summer's heat.

La Nina

I bought a small air conditioner for my chickens several years ago. They ought to be cooled off at night to lower their body’s core temperature.

If La Nina will be 2022-23,…

If La Nina will be 2022-23, it would be like we did in 2008-09, possibly 9.08 inches?

La Nina

At least for now. Some of the models are showing this La Nina event to be focused in the central and western portions of the Equator. Much different than what we saw last year with old SSTs focused in the Nino 1.2 and Nino 3. and near neutral waters in the Nino 4. Wonder what that may mean for winter if this is a central/west based La Nina versus an East Based event?

Hi Bob, Probably a bit too…

Hi Bob,

Probably a bit too early to say as there's a lot of time left between now and winter for the flavor of this La Nina. But it is something we'll be looking at. Each La Nina is, of course, one of a kind.

Winter La Nina

Eric Webb on Twitter posted about a strong trade wind burst happening and -2C SSTa in the Nino 3.4 region this winter. That would be a strong La Nina. None of the models thus far are supporting that. Is anyone at Climate.gov seeing that,

Without knowing Eric Webb on…

Without knowing Eric Webb on Twitter, I'll state that at this point we don't favor a -2C event brewing. We have ENSO strength forecasts at this link:

https://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/products/analysis_monitoring/enso_advisory/strengths/index.php

Which are updated once a month and right now an event < -1.5 (a strong La Nina) has about a 10% chance. Not nothing (1 in 10 times it will happen!) but low probability.

Thanks Michelle!

Thanks Michelle!

La Nina bad???

I live in Eastern Washington, and when talking El Nino vs La Nina events it seems no one bemoaning an La Nina event forgets the PNW and the effects of an El Nino on our water storage.

No one likes drought, but where will the SW be if we don't have enough water for Hydro power (which we provide) to share with them?

Is less water here better for California et al when they don't utilize Hydro power there anymore? I think not.

Hydro Power

That is false. California still uses Hydro power. More importantly, California is the leading ag producer in the world. Both ag and people in Ca rely on surface water supplies that come from melting snow that accumulates in our reservoirs. Add to that the past two years have been drier than normal. California is currently in a severe drought with low reservoirs. I don't think the situation in PNW is quite as severe.

So done with La Nina

The "little girl" can leave whenever she wants and not let the door hit her on the way out. I know that part of the reason for our Texas heat wave and drought is a stubborn jet stream and dome. But La Nina isn't helping.. I remember a similar La Nina event partially contributing to a really hot drought-heavy summer of 2011.

Add new comment