May 2022 ENSO update: piece of cake

La Niña continued through April, and forecasters estimate a 61% chance of a La Niña three-peat for next fall and early winter. Current El Niño/Southern Oscillation (ENSO, the entire El Niño and La Niña system) conditions, the forecast for the rest of the year, and some potential impacts are all on the dessert menu today.

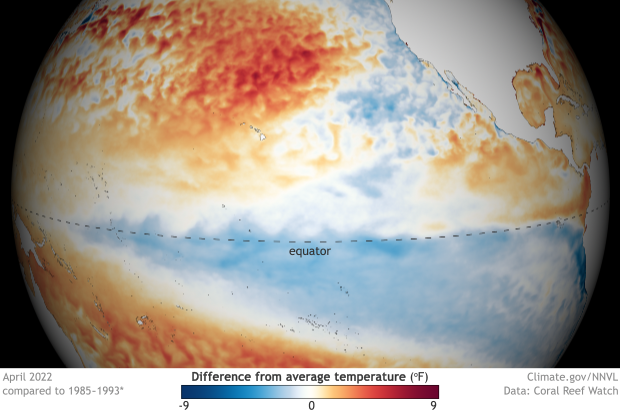

Still cool: Sea surface temperatures across the tropical Pacific remained below average in April 2022. NOAA Climate.gov image from our Data Snapshots collection.

Mix the butter and sugar together

We’ll start by measuring out the tropical Pacific ocean-atmosphere system. The first ingredient in any ENSO recipe is the sea surface temperature anomaly in the Niño-3.4 region of the Pacific. An anomaly is the difference from the long-term average; in this case, the average is 1991–2020. When the sea surface temperature anomaly in Niño-3.4 meets or exceeds -0.5 °C, we’re in La Niña territory. At -1.1 °C, April 2022 was tied with 1950 for the strongest negative April anomaly in the 1950–present record. That’s according to ERSSTv5, our most reliable long-term sea surface temperature observation dataset.

In the context of repeat La Niña events, the April average anomaly was noticeably stronger than any of the other 8 second-year La Niñas.

Three-year history of sea surface temperatures in the Niño-3.4 region of the tropical Pacific for 8 previous double-dip La Niña events. The color of the line indicates the state of ENSO for the third winter (red: El Niño, darker blue: La Niña, lighter blue: neutral). The black line shows the current event. Monthly Niño-3.4 index is from CPC using ERSSTv5. Time series comparison was created by Michelle L’Heureux, and modified by Climate.gov.

The atmosphere also continues to reflect La Niña, with plenty of evidence of an enhanced Walker circulation. The normal Walker circulation consists of a loop of rising air over the warm waters of the far western Pacific and Indonesia, west-to-east winds aloft, descending motion over the cooler central/eastern Pacific, and east-to-west winds near the surface (the trade winds). During La Niña, the even-warmer west Pacific and even-cooler east Pacific act to strengthen the Walker circulation. In April, both the trade winds and upper-level winds were stronger than average. Along with the April 2022 pattern of more rain than average in the western Pacific and less in the central/eastern Pacific, we have ample confirmation that La Niña conditions are still going strong.

Beat in the eggs and flour

So what’s in the oven? The odds of La Niña drop from 87% for the May–July average to 58% for August–October, before rebounding very slightly to 61% for the fall and early winter. In the short term, the trade winds are predicted to slow in the coming weeks, which would support a weakening of the cool sea surface temperature anomalies. Most current climate model predictions expect the negative Niño-3.4 anomaly will weaken over the summer and strengthen in the fall.

The range of forecasts for departures from average temperatures in the Niño-3.4 region of the tropical Pacific in 2022 from the North American Multi-Model Ensemble (NMME). The average of all forecasts (black line) is below the La Niña threshold. Sixty-eight percent of the forecasts (dark gray shading) are for neutral or La Niña temperatures. Ninety-five percent (light gray shading) are below El Niño temperatures. NOAA Climate.gov image from University of Miami data.

As we’ve mentioned a few times here on the ENSO Blog, we’ve had La Niña for three winters in a row only twice before:1973–1976 and 1998–2001. Both of those periods followed very strong El Niño events, while the current situation follows a somewhat warm, but officially neutral winter (2019–2020). ENSO is determined to keep us on our toes, for sure.

One final note about the forecast—we’re still within the spring predictability barrier, when ENSO forecasts are generally less accurate than forecasts made at other times of the year. We’ll start to clear this barrier next month.

Bake at 350 until set

La Niña has several important effects on US weather and climate throughout the year. These effects include links to increased severe spring weather and tornado activity through the U.S. Southeast. So far, 2022 has recorded more tornadoes than average. On the other hand, there are a lot of different factors besides La Niña at work in creating the conditions for severe weather. For instance, 2021’s La Niña spring featured a less active tornado season.

Another reason to care about the ENSO forecast is La Niña’s influence on the Atlantic hurricane season. La Niña conditions decrease the vertical wind shear—the difference between near-surface and upper-level winds—over the tropical Atlantic. Shear makes it harder for hurricanes to develop, so La Niña’s reduced shear can contribute to a more active hurricane season. NOAA’s official Atlantic hurricane seasonal outlook will be released on May 24th.

Last, but definitely not least, La Niña’s northward-shifted jet stream is associated with less rain and snow over large regions of the western and southern US (compare the seasons here). This can cause and exacerbate drought conditions.

Drought status across the United States as of May 3, 2022. More than half the country was in some level of drought, and an additional amount was abnormally dry (yellow). In many Western states, conditions were extreme (bright red) or exceptional (dark red). A third winter of La Niña is unlikely to be good news for the country's southern tier. NOAA Climate.gov map, based on data from the U.S. Drought Monitor project/Drought.gov.

More than half the contiguous US is currently experiencing drought, so I reached out to Brad Pugh, a drought expert at the NOAA Climate Prediction Center, for more information. Brad had this to say about current conditions:

According to the U.S. Drought Monitor, valid on May 3, 53.77% of the continental U.S. is designated with drought (D1-4), with severe to exceptional drought (D2-D4) mostly limited to the West and Great Plains. During the past three months, drought has worsened across much of the Southwest and central to southern Great Plains, which is consistent with La Niña during the late winter and spring.

The Drought Monitor is updated weekly on Thursdays; check out the site for lots of fascinating maps.

Brad continued:

The start of the widespread severe to exceptional drought across the Southwest was due to the failed 2020 monsoon. [That would be the North American monsoon, a critical source of rainfall for the southwest. The 2020 monsoon season was the driest and warmest on record for the Southwest.] The persistence and additional expansion of the drought during the past two years is related to the consecutive La Nina winters. La Nina typically favors below-normal precipitation and above-normal temperatures across the southern tier of the U.S.

As far as the forecast goes, Brad added,

the seasonal drought outlook through the end of July calls for drought persistence throughout much of the West, but there could be improvement later in the summer across Arizona as monsoon rainfall increases. The seasonal drought outlook for the summer will be released next Thursday, May 19.

Birthday cake

What’s with the cake theme? It’s the ENSO Blog’s 8th birthday! Hundreds of posts later, we still have a lot to say about ENSO and its extended climate family. Will we be here until the Blog can drive? Only time will tell!

Comments

Death of La Nina

Here is hoping La Nina dies in early winter as the odds are very close to not being La Nina and never to return again. Hoping a Super El Nino in the next season or two. Die La Nina!

There are no predictions by…

There are no predictions by any climate scientist of La Nina never returning again, and no indications of such.

just a joke

Indeed, but pretty sure he was just making a joke ;-)

La Niña is returning

I hope La Niña returns and El Niño doesn’t come back till 2100 El Niño wants u to shut up

2100

We are pretty confident that El Nino will not return in the short-term, but we are even more confident that we will El Nino will return multiple times before 2100.

The ratio between El Nino and La Nina

That they will follow one another is sequence is not that surprising.

The ratio between them decade on decade is much more interesting.

It has been suggested that we are in for a period of more La Nina than El Nino going forward.

la nina increase

statistical last 30 years twice as many La nina events as before that time. I would suggest that if global warming is climate change we should expect an increased number of La nina events. Going forward La nina events should continue to increase with each decade. that is my opinion.

ENSO in a changing climate

For more on the future of ENSO, check out Tom's post about the IPCC report.

Nina/Nino

Agreed!!!

Yikes!

A 3-peat will be disastrous for California- coastal cities, I believe will start looking hard at the ocean for at least part of it's source of water. It's too bad we cant get water from areas that typically get excess amounts. Then again, we have already overbuilt, and that would likely encourage more development. Sacramento needs to stop mandating growth in areas that can't sustain it.

Overbuilt?

Overbuilt in Sacramento? I'm sorry but that is just classic NIMBY brainwash talk. We are less dense than almost any European country, and we have been severly UNDERbuilt for years. Most boomers don't care because they have a bunch of equity, and they continue to push the "overbuilt" narrative in order to limit supply and build more equity. Shame on NIMBYs

Update to chart

CFSv2 has all of Aprils data now

https://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/products/CFSv2/imagesInd3/nino34Mon.gif

ENSO Blog

Great work here, thanks for the insight.

3rd Lanina Bet

Thanks for the update Emiley & Brad.

From the 95% confidence interval for the long-range forecast of the Enso someone could tell a third lanina is still plausible . I have a deep intuition that says in June forecast when the spring barrier is lessened we would see enhanced Likelihoods of 3rd Lanina ( Just a deep intuitive guess) .

Thank you again .

Warmest Regards from Jordan

Mohamed

Happy Birthday!

Happy Birthday, ENSO Blog! I've been following along since the inception of this blog, what you all are doing helps me plan seasonally, thank you!

While we here in NM are hoping against facts for rain, I really do appreciate all that you do for this blog.

Wow from the beginning!…

Wow from the beginning! Thank you so much for being dedicated reader.

I'm also hoping for a good monsoon for the Southwest too. Stay safe in New Mexico.

New Mexico Monsoons?

Any hope for monsoons in New Mexico in 2022? Or just Arizona? NM is burning up!

The wildfires in New Mexico…

The wildfires in New Mexico are awful.

Right now the latest seasonal outlook for Aug-October, doesn't favor any tilts in the odds towards drier OR wetter conditions. But forecasters will be paying a very close eye on the Monsoon this year.

https://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/products/predictions/long_range/seasonal…

La Niña 1908-1911?

Aa the excellent article points out only two triple Niña have emerged since 1950, both after a very strong El Niño. However, from Eric Webbs ENS ONI stretching back to 1850 there are indications that a triple La Niña developed in 1908-1911. ..I.e started by fall 1908 and lasted to spring 1911. That La Niña evolved after a moderate double Niño in 1904-1906 followed by neutral conditions from summer 1906 until summer 1908.

https://www.webberweather.com/ensemble-oceanic-nino-index.html

Thanks Andre, There is no…

Thanks Andre,

There is no doubt that more triple La Nina's have happened in the past. Though due to the lack of observations in the Pacific prior to 1950, there are bound to be larger error bars on any attempt to determine sea surface temperature anomalies in the Nino3.4 region.

That's why we only go back to 1950 with confidence.

Either way, this just illustrates the variability that exists within ENSO.

NorCal Rain Patterns

Out here in Sonoma County CA we received about 25 inches (normal=33inches) of rain during the 2019 to 2020 rain year. Definitely not an El~Nino-ish winter pattern, however the winter before that was pretty much a double rain, double snow year for the whole state and I think there may have been double El Nino just prior(2014-2016?). It would be interesting if the winter snow/rain totals in California for 1904~1911 are similar to 2015~2022. Kind of an interesting pattern nonetheless.

ps Happy Birthday Blog! It's always a good read

La Niña rev 3

Thanks for the great update! I’m North of your Northern Tier, so I follow this blog faithfully.

As a beekeeper, I try to figure out what the grrrlz will need going into Winter. You provide some great info that in turn inform my decisions. Thanks to you, and NOAA , for providing this info.

Brian T

PS - a special shout out to the American cousins that fund NOAA. Greatly appreciated. Magnificent organization that helps us all.

Thanks for the kind remarks!

Thanks for the kind remarks!

Ele Nino vai voltar

O Ele Nino vai voltar com força no final de 2022, explosões solares e máximo solar, com tudo, certeza!

Causes of Three Year La Nina

Is the PDO, AMO, or other teleconnections contributing to these repeated La Ninas or number of La Ninas the past several years. Is there anything that is making the conditions more favorable to having these La Ninas?

interesting question...

But probably will have to wait until next week for a response to this, as the blogger on comment duty this week is out of the office today. Stay tuned...

I will stay tuned Thanks…

I will stay tuned

Thanks Rebecca!

Thank you for the updates; I…

Thank you for the updates; I’m sad for California and hope your forecast changes as more data comes in.

LaNina

The latest CFSv2 model seems to be backing off on the strength and duration of this upcoming La Nina. Shows a borderline event that will be over by January. Hope the trend continues.

El Niño needs to die permanently

El Niño’s are evil they cause drought for Wisconsin in winter so that’s global warming I am sorry but I hate El Niño I wish El Niño would die permanently

Evil?

I am sorry that that you feel so negatively about El Nino - certainly it can bring negative impacts to some regions but it also brings positive impacts to others. Regarding El Nino and Wisconsin drought, there is a indeed a signal for dry conditions in Wisconsin, especially for January - March, as the ENSO composites page shows. However, the signal is not so strong that we should expect drought in Wisconsin for all El Ninos or even the majority of El Ninos.

Three year La Ninas

Hi Nathaniel,

Any thoughts on the question I posed earlier below?

Is the PDO, AMO, or other teleconnections contributing to these repeated La Ninas or number of La Ninas the past several years. Is there anything that is making the conditions more favorable to having these La Ninas?

PDO, AMO influences

Hi Bob, those are great questions, and the short answer is that I don't know. Starting with the PDO, it's important to note that the PDO represents, in part, a response to ENSO as well as other processes, and so it is difficult to disentangle the effects of the PDO on ENSO from the response of the PDO to ENSO. This article gives a nice review of the PDO for practitioners in the field.

However, North Pacific variability is known to impact ENSO through the Pacific Meridional Mode (PMM) - I recommend reviewing that guest post by Dr. Daniel Vimont. This article suggests that the PMM may be important for double-dip La Ninas and presumably three-year La Ninas as well. I haven't looked closely to see if there could be a PMM-like connection with the current forecast.

I also will note that the tropical Pacific has experienced a multidecadal La Nina-like trend with cooling temperatures in the tropical eastern Pacific and a strengthening Walker circulation that opposes expectations under increasing greenhouse gases. Could this reflect either natural variability or a radiatively forced response that has impacted the frequency of La Nina? We don't fully understand these recent trends, so I cannot give you an answer.

Regarding the AMO, there have been numerous studies suggesting that warming in the tropical North Atlantic is linked with La Nina occurrence (like here, here, and here). So, it is possible that there is an Atlantic connection, though it would take more investigation to firmly establish the causal links.

The bottom line is that it is intriguing that the NMME models have seen this signal for persisting La Nina conditions despite the absence of strong El Nino that typically precedes multi-year La Ninas. So, is this signal originating from other basins? Again, I don't have the answer, but it's an intriguing question.

La Nina

Thanks Nathaniel for such a detailed answer!

My pleasure!

My pleasure!

CFSV2 SST Model shows dying la nina before mid winter

The CFSv2 SST model is really putting on the brakes on another La Nina this winter. If some of those runs became reality it looks doubtful the temps will reach -5 for three consecutive months to be considered a La Nina and the SST anomalies in the 3.4 will become positive in january

Wildfires

I love El Nino dry winters and hot summers in the Pacific Northwest -but it would be a wildfire horror if it happened all the time. I’m trying to suck it up this spring and appreciate the above average rainfall and cooler temps in B.C. Maybe a less smokey summer? Though it IS awful about the continuing drought in California.

Add new comment