Details on the October ENSO Diagnostic Discussion: Trust, but verify.

Do we sound like a broken record? The CPC/IRI El Niño-Southern Oscillation forecast released today is essentially unchanged from last month, with around 60-65% chance of El Niño, starting in October-November. Sea surface temperatures in the Niño3.4 region are +0.3°C over the last week, a downwelling Kelvin wave continues to transport warm water toward the eastern equatorial Pacific, and global climate models continue to call for the development of a weak El Niño.

Just how good are these models, though? In our last post, Tony discussed ENSO forecasts over the last few years, including prediction for El Niño in the fall of 2012 that never materialized. Here, I’ll take a look at one forecast system to see how it performed compared to the past 33 years of observed ENSO episodes.

While dynamical climate modeling has been around for decades, many of the current models have only been in existence for a few years (for details on dynamical prediction models, see the footnotes from Tony’s post). For example, NOAA’s operational climate model, the NCEP Climate Forecast System version 2 (CFSv2), started producing forecasts in 2011. It is difficult to evaluate model performance with only a few years of forecasts. So, in order to get more years to study, we create forecasts based on historical records.

For example, we start with the observed state of the atmosphere and ocean in September 1997, and then let the computer model make a forecast out to 9 months (for the rest of 1997 and into 1998). Since we already know what happened in 1997-1998, we can compare the observations against this “retrospective forecast” (also known as a “hindcast”) to determine how well the model performed.

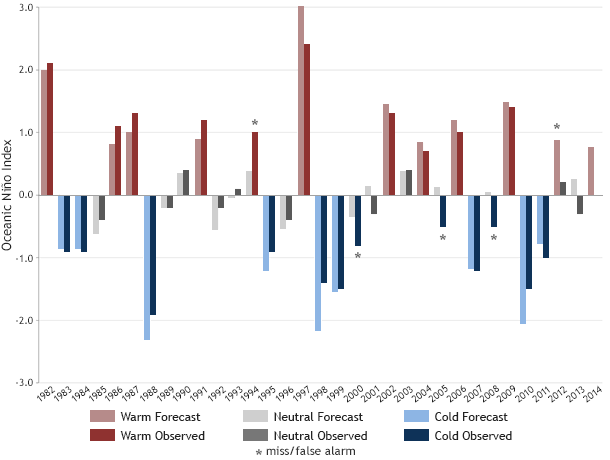

One of the tools we use in making the ENSO forecast is the North American Multi-Model Ensemble (NMME) forecasting system, a project that incorporates several global climate models, including the CFSv2. I looked at the September forecasts for October-November-December (OND) from 1982 – 2013, to see how the forecast tracked with the observations (Fig. 1). This system has been active since 2011, so I used 29 years of hindcasts (1982 – 2010) and three years of archived real-time forecasts (2011 – 2013). The exact same versions of the models are used for both the hindcasts and the forecasts, allowing for a continuous data set.

Forecast from the NMME (lighter colored bars) and observed Oceanic Nino Index values (darker bars). Red/blue bars indicate ENSO events; gray bars correspond to neutral conditions. The four "missed" forecasts, and the one false alarm (2012) are highlighted with asterisks. Figure by climate.gov from CPC analysis.

The forecast I looked at was the area-averaged sea surface temperature in the Niño3.4 region, averaged over a three-month period (this is also called the Oceanic Niño Index (ONI), NOAA’s indicator of ENSO). In the 1982 – 2013 period, we had 10 El Niños winters and 12 La Niña winters; the rest were neutral years. The NMME forecast I used is the combination of all the models (“ensemble mean,” the red line in Fig. 2).

Forecast from the North American Multi-Model Ensemble for the Nino3.4 index. The red line is the average of all the forecasts. Figure from NOAA climate.gov, using CPC data.

To get a “hit”, the system had to correctly forecast an ENSO event, based on five consecutive seasons with an ONI greater than +0.5°C (El Niño) or less than-0.5°C (La Niña.) The other possible outcomes are “miss”, when an ENSO event happened, but wasn’t forecast, and “false alarm”, when the forecast system called for an ENSO event, but it didn’t occur.

In the past 33 years, grouping all ENSO events together, the September forecast for October-November-December had 18 hits, 4 misses, and one false alarm (2012). The rest of the forecasts were “correct negatives” – forecasts for neutral conditions. The forecasts correlate with the observed ONI at a 0.95 coefficient. While this is a simplistic way of taking stock of the forecasts, it does give an idea of why we tend to trust the model forecasts made this time of the year, especially at such a short lead time. At longer lead times, for example, the June forecasts for October-November-December, there are 13 hits, 8 misses, and 3 false alarms.

A few other elements are giving forecasters the confidence to stick with the 60-65% chance of El Niño. One, the CFSv2 appears to have forecast many of the changes in subsurface ocean temperatures since May (i.e. oceanic Kelvin waves). Also, there are currently some westerly wind anomalies in the western Pacific, which may encourage more eastward heat transport across the tropical Pacific.

Finally, atmospheric conditions, as represented by the Southern Oscillation Index, remained in a borderline El-Niño-friendly state throughout September (SOI = -0.7 at the end of September.) So, while this year’s ENSO forecasts may sound like a broken record as we wait to see if the forecast hits, the track record of model forecasts for past El Niños and the current state of the atmosphere and ocean tell us that the odds are still for an appearance of El Niño this year.

**Editor's note: A draft version of this post was accidentally posted at 11 a.m. EST. The post was updated with the final version at 12:23 p.m.

Comments

portugal as indicator?

RE: portugal as indicator?

Although Portugal and California are similar in their basic climate (e.g. both have a Mediterranean climate), what happens to one in response to an El Nino does not at all necessarily have bearing on what happens in to the other. Further, recent rains in Portugal have little influence on the ENSO situation. ENSO may affect rainfall, but the rainfall does not feedback onto ENSO in any substantial manner. Of course, Portugal has much less of a late winter impact from ENSO than does southern California.

Are the models tuned with historical data?

RE: Are the models tuned with historical data?

This is an excellent question. In developing dynamical models, historical data is indeed used to validate/verify/evaluate model performance, and also to tune some of the parameters used in the models. Therefore, dynamical models are expected to do slightly better in hindcast model than in real-time mode. But the difference between their performance during the two periods (hindcast vs. real-time) is normally smaller than that found in statistical models, which train completely using hindcast data. A good portion of a dynamical model has explicit and completely represented physics, and that part is not tuned. Only where the physics needs to be abridged, as for example in representing tropical convection using grid points larger than the spatial scale of the convection, is there wiggle room for some tuning. But the question is very good. We note in the graph that the errors during the last 2 to 3 years, the real-time period, look a bit larger than those during the hindcast period. That should make us a little bit more worried about how well we can trust the model for the current prediction of weak El Nino coming in the next several months. If there is an error similar to that of the last 2 years (where the outcome was cooler than the forecast), we could end up getting only a marginal El Nino condition instead of a full-blown weak El Nino as predicted. On the other hand, assuming the error will be as that found during the last 2 years is also questionable. A sample of two cases is highly inadequate for coming to a conclusion or decision. The bottom line is that we must wait and see, and should trust the model to at least a moderate extent.

question about "missed" forecasts

RE: question about "missed" forecasts

The three missed forecasts for La Nina were those in the autumns of 2000, 2005 and 2008, as shown on the graph. All 3 cases ended up having weak La Nina. As for the ensuing winters in southern California (the part of the state most strongly affected by ENSO, especially in late winter), during Jan-Feb-Mar season we did observe drier than average conditions in 2001 (a few months after the missed forecasts were made), drier than average conditions in 2009, and in 2006 it was wetter than normal in central and northern California but near to slightly below normal in southern California. So we see that the observations did tend to follow the expected impacts, but not unfailingly. That is a typical rate of observing ENSO teleconnections--they show a tendency but not a guaranteed outcome.

El Nino

RE: El Nino

Yes, we are still in an "El Nino Watch" meaning we are expecting a full blown (weak) El Nino as of mid October 2014:

http://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/products/analysis_monitoring/enso_advisory…

Satellite Tracking

RE: Satellite Tracking

Yes, there are satellites which are relied upon to give us a complete picture of many tropical Pacific Ocean variables, such as sea surface temperatures, sea level height (which is an indicator of heat content below the surface of the ocean), and rainfall. I'm not familiar *which* satellites are relied upon, but suffice it to say without them, it would be difficult to measure what is happening with ENSO.

Does climate shift/change have any effect on El Nino?

RE: Does climate shift/change have any effect on El Nino?

Tom did a nice job describing the IPCC consensus on how ENSO relates to climate change here:

http://www.climate.gov/news-features/blogs/enso/enso-climate-change-hea…

There will be future ENSO blog articles that touch on some of the cutting edge work done in this area.

Global warming and Change in ENSO forecast skill stats?

RE: Global warming and Change in ENSO forecast skill stats?

Good observation. Since 2000, ENSO has shifted to lower variability, meaning we don't see the bigger amplitude events that we saw in the 80s/90s. The models in general have more difficulty forecasting weaker events and capturing the correct onset time. All those cases of misses/false alarms during OND since 2000, occured with the weaker events (< +/-1degC). The jury is out on whether this weaker ENSO variability is associated with climate change and it is very difficult to determine with the short lenght of the historical record. There are certainly papers that project weaker variability but there are also papers that suggest strong variability.

RE: Global warming and Change in ENSO forecast skill stats?

RE: RE: Global warming and Change in ENSO forecast skill stats?

As Michelle said above, there are many indications of a climate regime shift, particularly affecting ENSO, around 1999-2000. Recently, several ideas about possible weakening/slowing/changing of the Jet Stream have been proposed; while these ideas have solid physical bases, it is difficult to identify the cause-and-effect relationships in the very short observed record. However, this is a topic of extremely active research.

El Ninõ effects on Baja California Coast compared to 1997

RE: El Ninõ effects on Baja California Coast compared to 1997

Here is a nice article from the NOAA Northwest Fisheries Science Center that discusses the warm temperatures seen nearly along the entire eastern North Pacific Ocean:

http://www.nwfsc.noaa.gov/news/features/food_chain/index.cfm

I agree with their asessment that the cause is not straightforward at this time. However, while we have not officially entered El Nino conditions at this point (ENSO depends on physics in/over the Pacific Ocean near the equator), it is not unusual for certain atmospheric and oceanic variables to behave "El Nino-like" prior to onset. It is possible that warmer waters is consistent with the evolution *toward* El Nino, though the exceptionally above-average temperatures are certainly unusual and do not accompany every El Nino (or evolution toward El Nino).

Re: Dynamical vs. Statistical

RE: Re: Dynamical vs. Statistical

Good question. The statistical and dynamical models shown in the popular IRI/CPC plume of models do not all have the same "initial condtions," meaning they do not all have the exact same input data. Dynamical models often have a huge amount of atmospheric and ocean data, while the statistical models only receive input from less than a handful of variables (most often sea surface temperature). Also, the input data into these models can be based upon different time averages. In particular the statistical models often rely on monthly or seasonal (3-month) averaged inputs, while the dynamical models generally rely on daily or shorter averages. So we tend to believe the dynamical models are at an advantage simply because they see the most recent observational evolution better than many of the statistical models. However, there are certainly cases where statistical models performed better, so clearly this is only part of the story. But overall, in the last 10 years, we have generally seen better model performance from the dyanamical models over the statistical. Here is one paper that explores that:

http://journals.ametsoc.org/doi/full/10.1175/BAMS-D-11-00111.1 (is free/open access)

El Nino and "the northern pacific blob"

RE: El Nino and "the northern pacific blob"

El Niño and Fisheries

Add new comment