August 2019 El Niño Update: Stick a fork in it

The El Niño of 2019 is officially done. Near-average conditions in the tropical Pacific indicate that we have returned to ENSO-neutral conditions (neither El Niño or La Niña is present). Forecasters continue to favor ENSO-neutral (50-55% chance) through the Northern Hemisphere winter.

What’s on our plate?

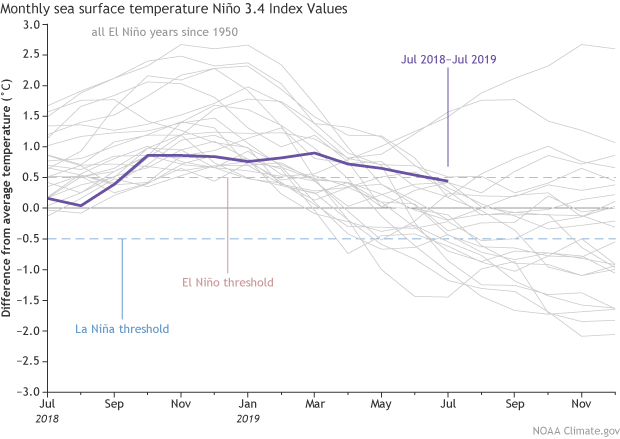

The July Niño3.4 index, our primary index for monitoring ENSO, was 0.4°C above the long-term average, falling below the El Niño threshold of 0.5°C for the first time since last September. In addition, tropical atmospheric conditions have trended toward neutral, as the cloudiness and rainfall over the Pacific were near average over the past month. The trade winds also have been near average lately, indicating that Walker circulation, which weakens during El Niño, has shown signs of rebounding.

Monthly sea surface temperature in the Niño 3.4 region of the tropical Pacific for 2018–19 (purple line) and all other El Niño years since 1950. Climate.gov graph based on ERSSTv5 temperature data.

Based on these latest indicators from the tropical ocean and atmosphere, NOAA forecasters have declared that El Niño has ended and neutral conditions have returned. Does a return to neutral mean that average weather conditions are expected to prevail around the globe? As Michelle pointed out a couple years ago, the answer is an emphatic NO. A return to neutral means that we will not get that predictable influence from El Niño or La Niña, but the atmosphere is certainly capable of wild swings without a push from either influence. Basically, ENSO-neutral means that the job of seasonal forecasters gets a bit tougher because we do not have that ENSO influence that we potentially can predict several months in advance (in a probabilistic form).

A change to neutral could also impact the Atlantic hurricane season, which typically ramps up this time of year and peaks in early-to-mid September. El Niño tends to produce hostile conditions for Atlantic hurricanes, as explained more thoroughly in Dr. Phil Klotzbach’s guest post, so a return to neutral means that we will not get a decisive push from El Niño to the Atlantic. The updated NOAA Atlantic Hurricane Season Outlook is now available, so be sure to check how these changing ENSO conditions and other drivers are impacting the Atlantic hurricane season.

Sea surface temperature from June 1 through July 27, 2019. The region of cool water in the tropical eastern Pacific, called the eastern Pacific cold tongue, is clearly visible along the Equator, surrounded by warmer waters to the north and south. The wavy features along the northern and southern borders between the cold tongue and the warmer waters are tropical instability waves. The waves on the north side are clearer in part due to the stronger temperature gradient on that side of the cold tongue. Map by NOAA Climate.gov from CDR data.

And just to drive home that ENSO-neutral doesn’t necessarily mean “bland and boring,” a closer look at the weekly ocean surface temperature reveals some fascinating, wavy features over the eastern Pacific. Emily discussed these interesting features, called tropical instability waves, a few years ago. These waves can produce some dramatic week-to-week swings in the Niño3.4 index, but their effects tend to get washed out in the monthly and seasonally averaged index. That doesn’t mean that these waves cannot impact ENSO – check out Emily’s post to find out more!

What’s on the menu?

Will ENSO-neutral conditions continue through fall and winter? Similar to last month, most of the computer models we consult predict that the ocean surface temperature in the Nino3.4 region will remain near average throughout this period. NOAA forecasters favor this outcome, predicting a 50-55% chance of neutral conditions remaining through winter.

Vertical bar histogram showing probabilities for La Niña (blue), neutral (gray), and El Niño (red) conditions for the remainder of 2019 and into early 2020. Thin lines show climatological (historical average) probabilities for these same three ENSO conditions. Figure from IRI.

Is it possible for an El Niño to end in the spring or summer only to reemerge again in the following fall? Yes, it can happen! (You can get a sense of this from close inspection of the first figure above.) We have seen this sort of situation a few times since 1950, the latest being the reemergence of El Niño in the fall of 1977. Some forecast models favor this outcome, and forecasters consider this plausible, but not the most likely outcome, predicting a 30% chance of El Niño next fall and winter.

The current forecast underscores that we don’t have a sure bet this far in advance – there are many possible outcomes for the coming fall and winter. The forecast probabilities still give us useful information on what outcome is favored at this time. As conditions evolve, we will gather more information that will allow us to refine these probabilities and hopefully narrow the forecast uncertainty. You can count on us to stay on top of these developments and to give you the latest!

This ain’t Mama’s home cookin’!

I know what you’re thinking – this blog post isn’t the same sweet, tasty morsel of freshly baked ENSO goodness that Emily usually delivers to us. I feel the same way. Emily is away this week, but don’t worry, she will be back soon for a post later in August. That means you’ll want to check back in a few weeks to satisfy your next ENSO craving!

Comments

Weather

RE: Weather

You can get our winter outlook (December-February) here:

https://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/products/predictions/long_range/

Forecasts are updated once monthly (3rd Thursday of the month).

RE: Weather

El Niño which stirs winds that tend to disrupt hurricanes?

RE: El Niño which stirs winds that tend to disrupt hurricanes?

Chances for an above-average hurricane season have gone up. Check out the story here:

https://www.noaa.gov/media-release/noaa-increases-chance-for-above-normal-hurricane-season

RE: El Niño which stirs winds that tend to disrupt hurricanes?

Weather forecast for central Calif.-2019/2020

RE: Weather forecast for central Calif.-2019/2020

CPC provides probabilistic forecasts for all sorts of climate timescales. Check out CPC's home page for the forecast timescale that may be of interest to you: https://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov

possible La Nina between late 2019 & 2021

Fall/Winter

Pacific

RE: Pacific

Good question! We wrote an entire blog post on this topic, which you can read here. In short, El Nino's lead to more hurricanes and the eastern/central Pacific and La Nina leads to less.

Love those tropical instability waves

Solar Minimum

El Nino to peak 26 December 2019, end 20 January 2020

Add new comment