May 2024 ENSO update: we’re 10!

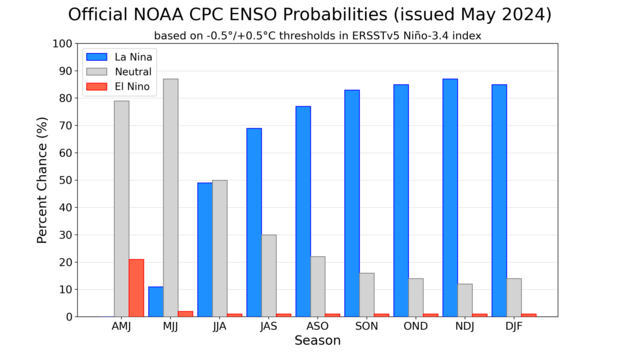

El Niño weakened substantially over the past month, and we think a transition to neutral conditions is imminent. There’s a 69% chance that La Niña will develop by July–September (and nearly 50-50 odds by June-August). Let’s kick off the ENSO Blog’s tin anniversary with our 121st ENSO outlook update!

Attention!

First things first: our beloved editor, Rebecca Lindsey, has trained us all very well, including being sure to acquaint our newer readers with the fundamentals of the El Niño/Southern Oscillation climate pattern, or ENSO. ENSO has two opposite phases, La Niña and El Niño, which change the ocean and atmospheric circulation in the tropics. Those changes start in the Pacific Ocean and affect global climate in known ways. El Niño and La Niña can be predicted many months in advance, giving us an early picture of potential upcoming temperature, rain, and snow patterns. When neither El Niño nor La Niña are present and conditions are more normal across the tropical Pacific, well, that’s ENSO-neutral conditions.

Hang 10

There was some discussion this week amongst our ENSO forecast team about whether El Niño, much weakened already early last month, is still present. El Niño is a coupled system, meaning the ocean and atmosphere both exhibit characteristic changes. The atmospheric half of El Niño is harder to detect this month; most of the standard equatorial Pacific atmospheric indicators (rain and clouds over the tropical Pacific, trade winds and upper-level winds) were pretty close to average.

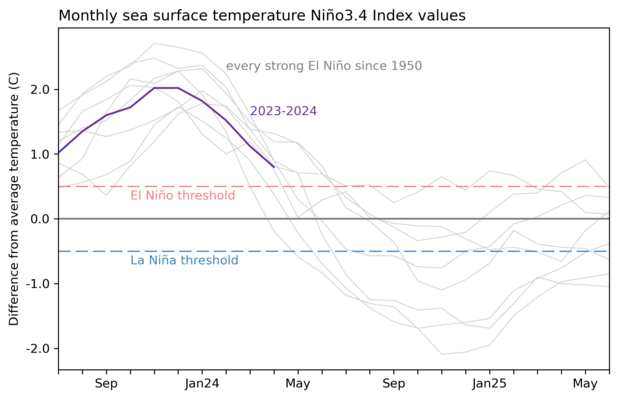

However, the April average sea surface temperature in the tropical Pacific was still 0.8 °C above average according to the ERSSTv5 dataset (average = 1991–2020). The latest weekly measurement, which comes from the OISSTv2 dataset, was 0.5 °C above average. Given that the El Niño threshold is 0.5 °C, the team decided we’re right on the edge of the transition to neutral conditions. We also can’t rule out some lingering El Niño impacts in other regions of the world.

Animation of maps of sea surface temperatures in the Pacific Ocean compared to the long-term average over five-day periods from April through early May 2024. El Niño’s warm surface has weakening and a region of cooler-than-average sea surface temperature has appeared. NOAA Climate.gov, based on Coral Reef Watch maps available from NOAA View.

Once this El Niño ends, it's likely that our spell of neutral conditions won’t be a long one, with La Niña expected to develop by the late summer and last through the early winter at least.

NOAA Climate Prediction Center forecast for each of the three possible ENSO categories for the next 8 overlapping 3-month seasons. Blue bars show the chances of La Niña, gray bars the chances for neutral, and red bars the chances for El Niño. Graph by Michelle L'Heureux.

We’ve seen a quick switch from El Niño to La Niña several times before in our 1950–present record, especially after a strong El Niño. This tendency is one source of confidence in the prediction that La Niña will develop later this year.

Other factors that provide confidence that La Niña is on the way include forecasts from computer climate models and cooler-than-average water under the surface of the tropical Pacific.

10-count

Even if the sea surface temperature in the tropical Pacific lingers near the El Niño threshold for a few weeks, it’s unlikely that there will be noticeable El Niño impacts on global climate conditions this coming summer. Nat looked at how the winter turned out in the US in his recent post, but El Niño causes changes in rain and temperature patterns all around the world, with related impacts on drought, food supplies, and flooding. You can look at El Niño and La Niña’s global patterns of temperature and rain/snow throughout the seasons here.

To get some insight into how this past winter turned out in other regions, I checked in with Steven Fuhrman of NOAA Climate Prediction Center’s International Desk (footnote). Steven had this to say about the effects from El Niño since December:

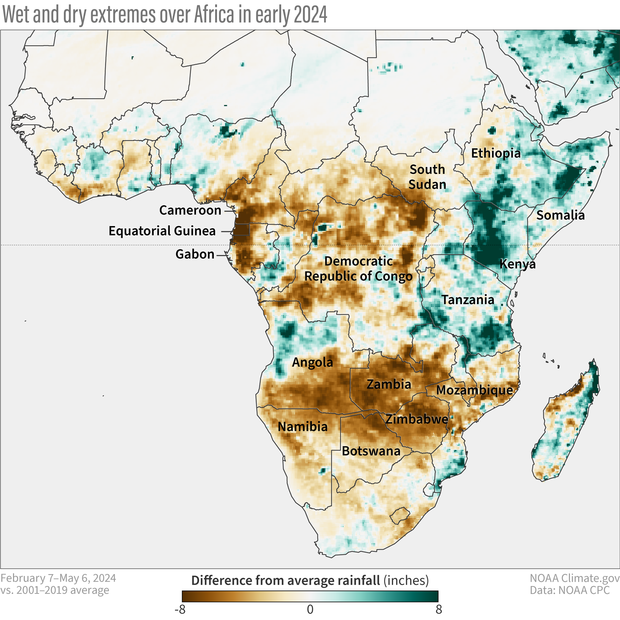

Expected El Nino patterns and impacts have played out in many parts of the globe. In Africa, there has been severe drought lasting through almost the entire rainfall season. Zambia, Angola, Botswana, and Zimbabwe were likely the worst affected countries. The worst impacts from drought in terms of food insecurity are likely still to come during the lean season. This is the time of year when access to sufficient food is the hardest; it can fall at different times depending on the place and livelihood. Recently, since early April, Kenya has been horribly impacted by flooding. Several rivers are exceeding 20-year return periods, and the latest I've seen puts fatalities at 228 with a total affected population of more than 205,000 due to displacement and disease.

The rainfall difference from average for February 7–May 6, 2024 for Africa. Brown areas indicate less rain than average, while green regions received more rain. Average is based on 2001–2019. Map by climate.gov based on CPC ARC2 data.

While many El Niño-related shifts in temperature and rain/snow are strongest during the Northern Hemisphere winter (December–February), some start earlier and last longer, especially in the tropics. One example is a tendency for drier and warmer conditions in central America and northern South America from September through March or April. Rebecca wrote about the impacts on the Amazon Rainforest back in the fall. Steven added this recap:

We've also observed expected hot and dry conditions over northern South America. Above-average temperatures were remarkably persistent during the second half of 2023 in Colombia and Venezuela. The broader region saw consistent rainfall deficits. This resulted in reduced water availability for both crops and livestock in the region. Another notable impact of the reduced rainfall was low water levels in the Panama Canal, which limited the transit of vessels through it for an extended time.

El Niño’s and La Niña’s shifts in temperature and rain impact communities around the world, including affecting global health and crop yields. This is why we spend so much time studying and predicting ENSO—it can provide an early heads-up of the possibility of severe impacts and allow people time to prepare.

Double digits

Speaking of so much time—who would have thought when we launched this blog back in May 2014 that we’d still have so much to say, 10 years later? In upcoming months, we’ll keep you posted on the ENSO forecast and discuss some of the climate shifts that can be expected during La Niña, including the likelihood of an active Atlantic hurricane season and drier winter conditions through the Southwest U.S. Also, I just checked our “ENSO Blog ideas” doc, which currently runs five pages long, so… here’s to another 10??

Footnote

Fun fact: For many years, Steven and I have regularly donated blood at our local hospital, along with some of our friends. There’s a national blood shortage in the U.S. right now—please consider visiting your local blood donor center!

Comments

Cookies in tin

Just came here to note that if anyone wants to send us "tin" for our 10th anniversary, I would like it to be filled with cookies. Anything lemon or peanut butter will be fine.

I'm not sure how this blog…

I'm not sure how this blog post became an ask for blood donations and cookies. ;-)

Happy 10 everyone!

cookies at blood drives

It must have been subliminal! I seem to remember being offered cookies at blood drives in the past...?

Year 10

Congratulations on 10 years of educating your readers on ENSO and how it affects them.

Happy 10th birthday to the ENSO blog - and many returns.

I just don't...

clearly understand how this past El Nino formed under a negative PDO and now is dying under a negative PDO. I thought that ENSO / neutral had a PDO of 0.00, but the current PDO ( April reading ) was holding at a negative 2.09. Nat told me in an earlier post that the PDO lags behind. For how many years ? Looking like La Nina will be for sure this Fall and Winter. That's bad news for Snow Lovers in the Ohio Valley. They were all disappointed this past Winter when El Nino didn't deliver any big time Snow Storms like they use to.

If I had the peanut butter fudge my Mother made years ago, I would send you all a batch. It was very delicious.

Happy Tenth Anniversary and Many more ! By the way Great May Blog.

Thank You,

Stephen S.

Thank you!

Thank you, Stephen! I am all about anything with peanut butter, so I imagine that peanut butter fudge was amazing. :-)

Regarding the PDO, I admit that I do not know all the factors that are contributing to its persistently negative state recently, and I think it's quite unusual that we had a strong El Nino concurrent with a strongly negative PDO. I will just reiterate that there are several factors separate from ENSO that influence the PDO (discussed, for example, in this paper), so it is possible that these other factors (reemergence of subsurface ocean temperature anomalies, ocean gyre dynamics, stochastic North Pacific atmospheric forcing, etc.) could counter the ENSO influence and lead to ENSO/PDO phasing that differs from the historical norms.

From what I saw, there were some changes in North Pacific sea surface temperatures in the PDO region that were consistent with the influence of El Nino, like the warming along the West Coast of the United States. However, the strengthened Aleutian low was displaced a bit farther east than normal, and high pressure to its west likely helped to maintain the warmth in the central North Pacific. I also wonder if ocean Rossby wave dynamics could have played a role in that region.

I understand the frustration about the snow. Here in New Jersey it feels like it has been forever since we had a classic, big snowstorm. We got a little more this winter than the previous one, but our snowfall was still below average for the third winter in a row.

Southern Pacific

An excellent 10 years it's been. Thanks for all the interesting blogs and information. I have a question on the Southern Pacific and Indian Ocean. Do low pressure storm activities(pressures, winds, swells, etc.) increase in the Southern Pacific or Indian Ocean either with El Nino or La Nina? Especially during the Southern hemisphere winter.

Southern Hemisphere

Thank you, Bailey! That's a good question - yes, El Nino and La Nina do have impacts in the Southern Hemisphere winter. The teleconnections to the Southern Hemisphere regions work in basically the same way as they do in the Northern Hemisphere, though El Nino and La Nina tend to be weaker in austral winter than in boreal winter. This previous post shows some of the typical impacts of El Nino during austral winter (you can reverse the sign of the impacts for La Nina). In an analogous way that El Nino and La Nina influence North American climate through the Pacific-North American (PNA) pattern, El Nino/La Nina can excite a similar pattern in the Southern Hemisphere called the Pacific-South American (PSA) pattern.

Strength of La Niña expected (May Update)

Hi. Is there any update this month on the potential expected strength of the La Niña? Many thanks :)

See below!

See below!

Expected La Niña strength - May Update (Wisconsin)

Hi I was wondering if you could provide an update on the expected strength you are forecasting for the La Niña this year. I am moving from the U.K. to Wisconsin and am curious how cold it may get this winter.

Thanks :)

La Nina strength outlook

Sure! This website gives you the latest forecast probabilities for different La Nina strength thresholds. For example, CPC forecasts an 85% chance of La Nina (Nino-3.4 index less than or equal to -0.5C) and a 30% chance that the La Nina will be strong, with Nino-3.4 index less than -1.5C, in the upcoming December-February. I also note that you can find the average La Nina temperature anomalies for Wisconsin and other regions of the US at this site. You also could use this site to view the expected La Nina impacts.

Thanks Nat for....

your reply. I am understanding better about the PDO / and ENSO. I think this is an interesting subject of Meteorology. Hoping the next El Nino forms under a positive PDO and then the big Snows will fly.

Thanks again,

Stephen S.

Negative PDO

I’m wondering if you or anyone else has a good guess when we will finally shift back into a Positive Phase of the PDO? It seems like we have been in this -PDO since around 1997. These Negative PDO/ La Niña combinations have really created some significant dry anomalies over Texas and the Southern Plains during this stretch.

This current El Niño has provided us some much needed relief from drought conditions but I anticipate a return to reality this time next year with a fully coupled La Niña / -PDO combo. Thanks.

I'm guessing it will happen…

I'm guessing it will happen when/if these tropical SST trends become less of an issue. Research has shown the PDO has a large contribution from the tropical Pacific.

PDO: Cause or effect?

So, I read the blog post you attached a link to that explained the PDO in brief. And, it seemed like a pretty good explainer.

That said, I had a couple of questions about it:

1. Based on what you wrote, the PDO is an effect of different processes in the Pacific and in the atmosphere (including ENSO and a warm ocean current in the Western Pacific [I forget the third one - was it the Aleutian low?]). Is this so?

2. From what was written there, the PDO does not appear to cause any global weather phenomena, though it appears to play a role in local ones. So, based on the best available evidence, does it contribute to any of them (such as whatever state ENSO is in, how wet or dry the west coast is during the winter, or other regional or global phenomena)?

3. You mentioned writing about a connection between ENSO and the Hadley Cell. Would you include a link to that post, please?

Thank you for reading this, and I look forward to hearing from you.

I'm not an expert on the PDO…

I'm not an expert on the PDO, but yes, researchers have shown that the PDO is based on different processes. A primary driver is ENSO, however (paper). So, for the CONUS impacts, the best predictor to examine for seasonal temperature and precipitation is ENSO. Even the local impacts along the U.S. West coast this past El Nino event were quite warm despite the negative PDO state (which would have contributed to cooling had that factor dominated). Here is the blog post that mentions the Hadley circulation. Thanks!

PDO & ENSO

Thanks for the reply, thanks for the explanation, and thanks for attaching a link to that post on ENSO and the Hadley cell.

As an aside, the PDO sounds like a really interesting phenomenon. So, are there other ENSO Blog posts that explain it in more detail?

Besides this post, the PDO…

Besides this post, the PDO is discussed in several other posts

https://www.climate.gov/news-features/blogs/enso/how-much-do-climate-pa…

https://www.climate.gov/news-features/blogs/enso/other-climate-patterns…

SST indicators "off the charts"

10 years of awesome work, thank you ENSO Blog team! This is probably the best ENSO resource for the broader (ahem, worldwide?) public. 10 years is an amazing milestone, hope we get another 10 more!

Anyways - gadzooks - the latest news from your NOAA hurricane forecaster colleagues is the Atlantic is on the edge of a busy, possibly the most active hurricane season ever on record... ...Isn't this slightly atypical for an El Nino transitioning into La Nina year?

Stranger still is the Atlantic (historically) cools down during El Nino phases, but it seemed quite hot through the 2023-24 El Nino. Are we witnessing a change in global oceanic and atmospheric systems? This is a question no one really seems to be asking (some even scorn the idea) but alas, it must be asked!

Thanks again and cheers!

Thanks Jim! We've seen some…

Thanks Jim!

We've seen some pretty active years that started in January in El Nino and ended December in La Nina. 2010 is a good example. Now we'll have to see if the forecast La Nina develops but if it does, it will most likely provide environmental conditions conducive to a busy year.

And you hit the nail on the head with noting how warm the global oceans have been. It's certainly a wildcard in all of this, and I don't believe there is a great answer yet as to why the ocean as a whole (and the Atlantic in particular) have been so warm. Looking at forecasts, it doesn't appear that warmth will stop (outside of the tropical Pacific)

La Nina/Positive IOD?

First of all, congratulations on 10 years with this blog, it's really amazing how far you've come as to what state the ENSO is currently at from month to month. Here's hoping that it will continue for years to come.

It's interesting to note that the Australian counterpart has declared that El Nino is over as of mid-April and are now on La Nina Watch as of mid-May. But it's also interesting to note that for seven weeks, a positive IOD was developing only for it to be stalled, although it could develop again albeit marginally on average.

I would like to know if La Nina does develop this year, how often does it occur with a positive IOD if that were to develop and how would this impact the summer, fall, and winter forecasts across North America if both events came to fruition? Usually La Nina often, although not always, is associated with a negative IOD, so this here would be quite unusual.

IOD

It will be interesting to see how the IOD evolves with this event. For example, I noticed that the latest GFDL SPEAR forecasts showed a more positive IOD than last month's forecast, but it looked like the IOD was still forecast to be neutral. So, a positive IOD with La Nina would be unusual, but I don't think that outcome is certain.

As Emily noted, the IOD impact on North America wouldn't be expected to be strong, although there is some evidence that the unusually strong IOD in 2019 may have been a factor in the positive NAO in early winter. That also would have impacted North American climate. See, for example, this and this study.

You're right, La Nina does…

You're right, La Nina does tend to trigger negative IOD. IOD doesn't have a strong association with impacts across North America, though. Check out this post by Nat about the IOD.

CP event

While too soon to trust SST models, is there any chance we will experience a CP or mixed La Nina type this year? Looking that the future SST models it seems to show the coldest temps in the Nino 3.4. Warmer temps into Nino 1.2. Seems coldest SSTs are in the Central Pacific.

La Nina flavor

We'll keep an eye out to see what sort of "flavor" evolves with this La Nina, although I will note that not all scientists distinguish Central Pacific (CP) La Nina from Eastern Pacific (EP) La Nina like they do for El Nino. One reason is that La Nina typically has more of a CP-centered pattern than El Nino, especially when you compare strong La Nina with strong El Nino - see my previous post that discusses ENSO asymmetry. So, if we do see a more CP-like La Nina, that would be pretty typical!

La Nina

Thanks Nathanial!

Seems with our recent La Ninas the Nino 1.2 region and NIno 3 regions were cold with low SST temp departures. Maybe that is the wrong way of looking at that.

One of the reasons I don't…

One of the reasons I don't love defining ENSO events based on their 'flavor' is that they are shape shifters. If you look at the onset season, the max/min SST anomalies may be in the eastern Pacific. But then later on, during the peak, it could be more centrally Pacific located. Or vice versa. I think Nat was focusing on the flavor at peak.

Central Based La Nina

Thanks Michelle!

I was curious about what would happen during the peak season winter months.

Blood shortage

If blood is needed Red Cross needs to make it easier to donate. I and several friends have been turned away due to not having an appointment. Can't walk in any more.

Add new comment