El Niño: Fizzle or Sizzle?

July was a rough month for the potential development of El Niño. Waiting for El Niño is starting to feel like Waiting for Godot. As Emily discussed in her post and as the CPC also described in the August 7th ENSO discussion, the trends were in the opposite direction of El Niño, particularly with respect to the ocean. Below-average temperatures emerged at the surface in the eastern equatorial Pacific and were widespread below the surface. The appearance of seemingly unfavorable conditions has led to some comparisons with 2012, when an emerging El Niño instead collapsed. Are we in 2012 territory again? Is this El Niño again a bust?

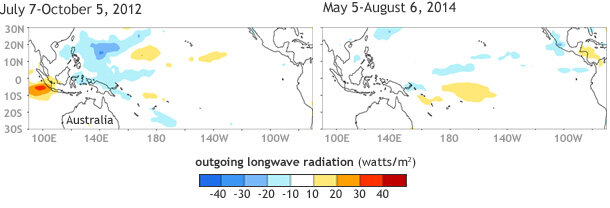

In 2012, sea surface temperatures were certainly above their normal average, but the atmosphere remained fickle. In fact, certain atmospheric features across the tropical Pacific remained more suggestive of La Niña, the opposite condition of El Niño. Namely, rainfall was above average near the Maritime Continent (north of Australia), which is a common feature associated with La Niña.

Outgoing Longwave Radiation (OLR) anomalies (departures from average) for early July - early October 2012 and for early May - early August 2014 (up to present). Blue shading indicates regions of increased rainfall, while yellow/orange shading show regions of decreased rainfall. NOAA OLR data (Liebmann and Smith, 1996) using a 1981-2010 base period. Map by Michelle L'Heureux, Climate Prediction Center.

In 2014, we have again struggled to see clear atmosphere-ocean coupling (i.e. interaction). For several months, the Niño-3.4 index (which tracks sea surface temperature anomalies in the east-central equatorial Pacific) increased, but then we saw that index lose ground in July. While the weakening is likely due to the lack of an atmospheric response, the atmosphere has not looked as La Niña-like as it did in 2012: for example, the enhanced rainfall near the Maritime Continent in 2012 is absent in 2014. In other words, while the atmosphere isn’t yet acting like El Niño, at least it’s not acting like La Niña.

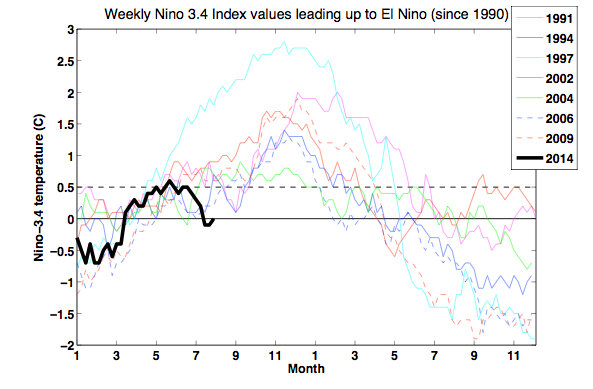

Also, this sort of summertime lull in warming in the east central equatorial Pacific is not unique when you look back at the more recent historical record. Below is the weekly Niño-3.4 index for consecutive two-year periods during which El Niño was present during the winter. The thick black line shows values since January 2014.

Two consecutive years of Niño-3.4 index values for El Niño episodes that peaked during the Northern Hemisphere winter. The thick black line shows the values of Niño-3.4 for the current year (2014) up to present. The dashed (solid) horizontal line shows where the Niño-3.4 index is equal to 0.5°C (0°C). Data based on weekly OISSTv2. Figure by Michelle L’Heureux, Climate Prediction Center.

Several times in past years the Niño-3.4 temperature anomaly index lost ground for a time after an initial increase. For example, the events starting in 1994 and 2006 had summertime lulls, but went on to become moderate-strength El Niño events (peak SST anomaly ≥ 1ºC). It is interesting that these short-lived dips occurred in the June or July time period, which seems to imply that the Northern Hemisphere summer season might be a tough time for El Niño to develop if the event hasn’t already become more firmly rooted (1).

As Emily showed, this recent decrease was predicted 1-2 months ahead of time (with certain models, like CFSv2 showing hints at a warming plateau since early May 2014). This advance notice strongly implies some models saw something in the climate system that accounts for the lull (we have speculated on one feature here).

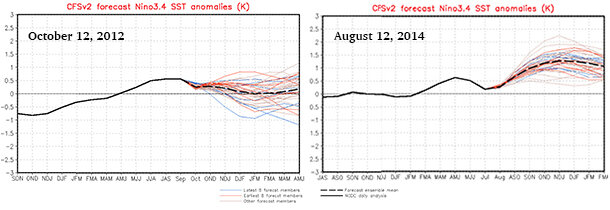

In contrast, during 2012, once the Niño-3.4 temperature index started to decrease, many models started to anticipate that El Niño was not going to occur. Currently we are waiting to see the latest runs from many of these models (see IRI/CPC’s mid-monthly update of the ENSO plume here), but we can examine NWS/NCEP’s CFSv2, which is run every day. Clearly, the CFSv2, unlike in 2012, is not favoring a bust at this point. Though some members (thin lines) suggest that outcome, so it cannot be ruled out either.

NCEP Climate Forecast System (CFSv2) predictions of the Niño-3.4 index made on October 12, 2012 and August 12, 2014. Index values greater or equal to 0.5°C (see y-axis) for consecutive seasons are considered El Niño episodes. The thick black line is the observed values of the Niño-3.4 index. The thick dashed line is the ensemble average of the individual forecast members, which are displayed as the thinner lines. Figures by Wanqiu Wang, Climate Prediction Center.

In summary, we continue to favor the emergence of El Niño in the coming months, with the peak chance of emergence around 65% (i.e. there is a 35% chance of El Niño not occurring). ENSO forecasters do not expect a strong El Niño (we can’t eliminate the chance of one either), but we are not expecting El Niño to “fizzle.” In fact, just in the last week, we have started to see westerly wind anomalies pick up near the Date Line. Literally and figuratively, we may be witnessing the start of ENSO’s second wind.

Footnote:

(1) One Northern Hemisphere summer feature is an east-west “band” of tropical rainfall that is normally positioned north of the equator. This band is called the Inter-tropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ). Because most tropical rainfall falls in this region, changes in intensity or departures in the position of the ITCZ will sometimes result in anomalies north of the equator. The formation of ENSO events, on the other hand, is usually associated with anomalies in rainfall and winds that occur directly on the equator.

Comments

re: El Nino regaining strength?

RE: re: El Nino regaining strength?

The exact reasons for why we may see a "second wind" of development remain mysterious to us. While ENSO is an anomaly (i.e. departure from the average or departure from the normal seasonal cycle) it is "phased locked" to the seasonal cycle, meaning that it tends to form sometime during mid-year and then is at its maximum around the Northern Hemisphere winter. So clearly the seasonality plays an important role in ENSO.

La Nina and 2014/2015 winter

RE: La Nina and 2014/2015 winter

NOAA CPC puts out seasonal outlooks for temperature and precipitation each month. Keep in mind the color shading refers to probabilities (% chance of above or below average). You can see the current set here:

http://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/products/predictions/90day/

And here is the current outlook for December-February:

http://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/products/predictions/long_range/seasonal.p…

El Nino

RE: El Niño: Fizzle or Sizzle?

RE: RE: El Niño: Fizzle or Sizzle?

In general, anomalies of subsurface temperature move from west-to-east along the equatorial Pacific. So, if your heat content index is shifted westward of another index, then there will likely be lead-lag correlations. In general, oceanic Kelvin waves take ~2-3 months to cross the Pacific and are one of our predictors for ENSO (not our only one!).

Your caveats are spot on. Taking in account sample size and using multiple datasets are excellent practices to follow.

EL NINO SOUTHEAST ASIA - SOUTH ASIA

El Nino in California

RE: El Nino in California

At this time we are leaning towared a weaker El Nino. In this post, we show what rainfall has historically been like over the U.S. during different El Ninos (ranked by peak strength of El Nino):

http://www.climate.gov/news-features/blogs/enso/united-states-el-niño-i…

ITCZ

During El Nino, the ITCZ

During El Nino, the ITCZ typically moves equatorward. With that said, in part due to increased warmth in the tropical eastern Pacific, El Ninos favor a more active eastern Pacific tropical cyclones.

As for the Southwest U.S. summer monsoon, there is a very slight tilt toward increased rainfall. There is more information about the SW monsoon on the CLIMAS webpage (along with podcasts that discuss current/expected conditions): http://www.climas.arizona.edu

Monsoon: http://www.climas.arizona.edu/sw-climate/monsoon

Kelvin Waves and Westerly Winds...

RE: Kelvin Waves and Westerly Winds...

These are all good questions with uncertain answers from my perspective. There is no one distinct area that is important. Any wind anomaly over the equatorial (5S-5N) Pacific is something to watch and monitor because of its potential influence on surface and/or subsurface temperatures. In general, wind anomalies that are persistent or strong (i.e. for El Nino, not just westerly winds in the *anomaly* but also in the *total winds*) have more of an impact than more fleeting, weaker anomalies.

As for the impact of the most recent westerlies, I believe it has already helped to keep some of the surface warmth in place (for example, we saw an abatement in the decrease of the Nino-3.4 index over the past week). Whether it helped to force a new oceanic Kelvin wave, that still needs to play out a bit more in the observations, but there is a chance it did.

I find these indices of subsurface ocean temperatures to be useful. They are based on data from the NCEP Global Ocean Data Assimilation System (GODAS):

http://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/products/analysis_monitoring/ocean/index/h…

More GODAS information is available here: http://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/products/GODAS/

El Niño: Fizzle or Sizzle?

El Nino Predictors

Southern hemisphere and Africa

RE: Southern hemisphere and Africa

Thanks for the comment Peta. You are certainly correct in noting that El Nino's have a global impact (and not just in the northern Hemisphere). You can see here the precipitation patterns for ENSO events in December-February for the globe. In the top picture, it can be seen that there is a dry signal in southern Africa during El Nino events.

As for climate change and ENSO, stay tuned for future posts.

Hope for RSS subscription

RE: Hope for RSS subscription

You can subscribe to the climate.gov RSS feed here:

http://www.climate.gov/news-features/feed.xml

and our twitter handle is @NOAAClimate

Add new comment