September ENSO update: La Niña Watch!

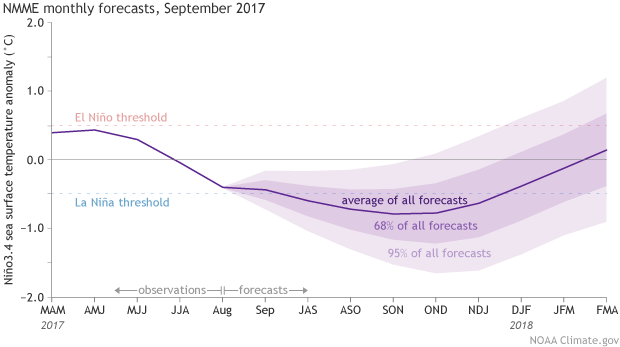

The September ENSO forecast is out!! (Can you tell I’m excited to be back on the top-of-the-month post?) Forecasters think there is an approximately 55-60% chance of La Niña this fall and winter, so we’re hoisting a La Niña Watch. Read on to find out what’s behind this development!

Summer summary

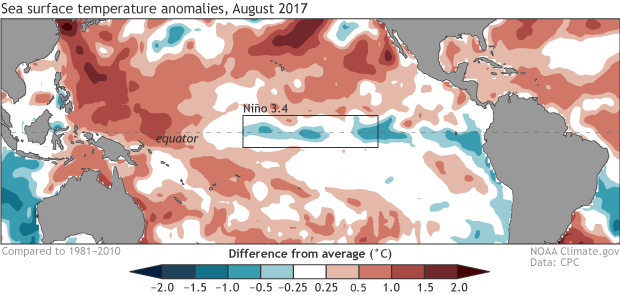

First, though, a quick recap of current conditions in the tropical Pacific Ocean. The sea surface temperature in our favorite Niño3.4 region in the central Pacific was about 0.1°C colder than the long-term average over June – August, smack-dab in the neutral range. The atmosphere also reflected neutral conditions during the summer, with the winds above the equatorial Pacific neither particularly enhanced nor weakened, and an average pattern in the clouds and rainfall.

While neutral prevailed during meteorological summer (what we call June – August, while the summer solstice through the vernal equinox is “astronomical summer”), we began to see some indications over the course of August that a change may be afoot. The first of these is the downward trend in central Pacific sea surface temperature anomalies (departure from the long-term mean) from July into August, with the August average in the Nino3.4 region of about -0.4°C, using ERSSTv4 data.

Winds and waves

One of the many environmental factors that we monitor closely is the temperature of the tropical Pacific below the surface of the ocean. Over the course of a couple of months, areas of cooler or warmer water can grow or move below the surface of the Pacific from west to east along the equator. These blobs (often in the form of oceanic Kelvin waves) often rise to the surface as they approach the eastern Pacific Ocean, and so give us a heads-up of how the surface may look in the near future.

It just so happens that during August, an area of cooler-than-average water developed around 50-150 meters (~160-500 feet) below the surface of the Pacific.

Departure from average of the surface and subsurface tropical Pacific sea temperature averaged over 5-day periods starting in early August 2017. The vertical axis is depth below the surface (meters) and the horizontal axis is longitude, from the western to eastern tropical Pacific. This cross-section is right along the equator.

Subsurface Kelvin waves are triggered by changes in the wind at the surface. The trade winds normally blow from east to west across the surface of the equatorial Pacific, keeping warmer surface water trapped in the western Pacific Ocean. If the winds weaken or strengthen, they can sometimes—but not always; this is a complex system—kick off Kelvin waves. In the case of an upwelling Kelvin wave, such as what we saw over the last month, the winds across the equatorial Pacific have strengthened, pushing harder on the surface waters and allowing cooler water to upwell from the deep ocean.

Since fall of 2016, the overall wind pattern has tended toward slightly stronger-than-average trade winds in the central and western Pacific, with a brief interruption in April 2017. This pattern is a little La Niña-ish, despite a lack of cool sea surface waters, and it’s one of the reasons we didn’t have a lot of confidence this past spring in the climate model forecasts for El Niño.

During the second half of July, the trade winds puffed a bit harder over the western half of the Pacific, likely helping this current Kelvin wave form. The complexity of the ocean-atmosphere system, where changes in one feed back into the other, means it’s difficult to diagnose a “cause” of the strengthened trade winds. I caught up with Steve Baxter, one of our Madden-Julian Oscillation (MJO) experts here at the Climate Prediction Center. He said the stronger trade winds during July were likely related to a short-lived MJO, but the signal wasn’t very clear.

Model citizen

The other major factor playing into forecasters’ consensus that conditions are favorable for the development of El Niño or La Niña conditions within the next six months (the criteria for a La Niña Watch) are the forecasts from the dynamical computer models.

Climate model forecasts for the Niño3.4 Index, from the North American Multi-Model Ensemble (NMME). Darker purple envelope shows the range of 68% of all model forecasts; lighter purple shows the range of 95% of all model forecasts. NOAA Climate.gov image from CPC data.

The ensemble of models from the North American Multi-Model Ensemble (NMME) is predicting that La Niña will develop this fall, and last just through the winter. Back-to-back La Niña winters are not uncommon, and have occurred at least five times since 1950, most recently in 2010-2011 and 2011-2012.

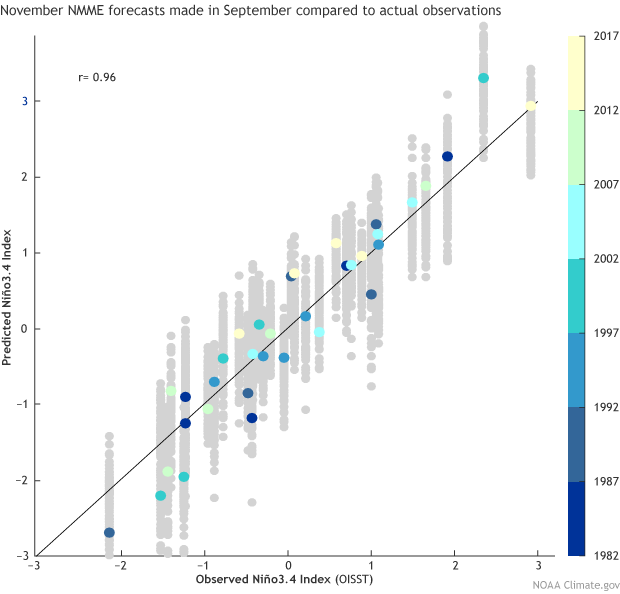

We are giving credence to the model forecasts because there is supporting physical evidence (that subsurface cooler water I was going on about a few paragraphs ago) and because September forecasts of Niño3.4 sea surface temperature have historically been fairly accurate.

The relationship between NMME forecasts for Nino3.4 sea surface temperature and the observed values, based on archived forecasts from 1982 – 2017. Forecasts shown are made in September for the November sea surface temperature. Each dot represents a single forecast: gray dots are individual model forecasts, and colored dots are the NMME ensemble mean. Predictions are on the y-axis, with the corresponding observed values shown on the x-axis. Climate.gov figure based on data from Michelle L’Heureux.

Michelle analyzed 36 years of predictions from the NMME, and found that September forecasts for November Niño3.4 sea surface temperatures have a strong relationship with what actually happened (0.96 correlation value, where 1.0 means they follow exactly). So, while they’re not perfect—if they were, all the colored dots would be exactly on the diagonal line—they’re usually reliable.

Watch on

In short, forecasters think that the sea surface in the Niño3.4 region will continue to cool, and the atmosphere will respond with a strengthened Walker circulation—the characteristics of La Niña. While chances of La Niña do have the edge in the current forecast, the odds only top out at about 60% likelihood that La Niña conditions will prevail in the winter. Climate forecasters will take this into consideration when developing the forecast for this coming winter, which will be released in October.

Comments

climate for Argentina

RE: climate for Argentina

For the generalized impacts of La Nina across the globe, please head here. The usual caveats apply though that these are just the typical impacts seen during La Nina and that reality can often times be different due to competing climate patterns and random weather.

Warmer temperatures elsewhere - how do they figure into forecast

RE: Warmer temperatures elsewhere - how do they figure into

Good question! Even though scientists are forecasting what the sea surface temperatures will be like in a specific area of the central/eastern Pacific Ocean, scientists still look at the whole Pacific when we are forecasting. This is because ENSO is a coupled atmosphere-ocean pattern.

Winter Outlook

No La Niña if everywhere if

La Nina

RE: La Nina

Hello Norma, I suppose it depends on what you define as good or bad. Here is a link to the typical impacts seen across the United States during a La Nina winter. In general, the Pacific Northwest tends to see a wetter than average winter during La Ninas.

nice post

am i reading this correctly?

RE: am i reading this correctly?

Good catch! That should read autumnal equinox.

The info contained and the write-up

Sept ENSO update

Badass! I love the the 3d

SE US Natural Resources Winter Outlook

RE: SE US Natural Resources Winter Outlook

Thank you! Yes, we now can be quite confident in the fall forecast of ENSO region SSTs. However, keep in mind that there is additional forecast uncertainty about how ENSO conditions will connect with SE US winter conditions. Even if we can be quite confident in the ENSO signal over the SE US, those pesky random weather variations unrelated to ENSO (what we scientists call "internal atmospheric variability") can lead to much wider uncertainty than in the short-term SST forecasts. Basically, this is just a reminder that we shouldn't a expect such a high correlation for local conditions over the U.S., but it's still reassuring that the uncertainty in ENSO conditions this fall and winter is diminishing.

Add new comment