EN... SO?

Forecasters at the Climate Prediction Center haven’t declared El Niño conditions, even though the Niño3.4 index is currently around 0.5°C above normal, and has been for the past two months. What’s the hold up? In short, we’re waiting for the atmosphere to respond to the warmer sea-surface temperatures, and give us the “SO” part of ENSO.

SO what? The Southern Oscillation, that’s what. The Southern Oscillation is a seesaw in surface pressure between a large area surrounding Indonesia and another in the central-to-eastern tropical Pacific; it’s the atmospheric half of El Niño. Since ENSO is a coupled system, meaning the atmosphere and ocean influence each other, both need to meet the criteria for El Niño before we declare El Niño conditions.

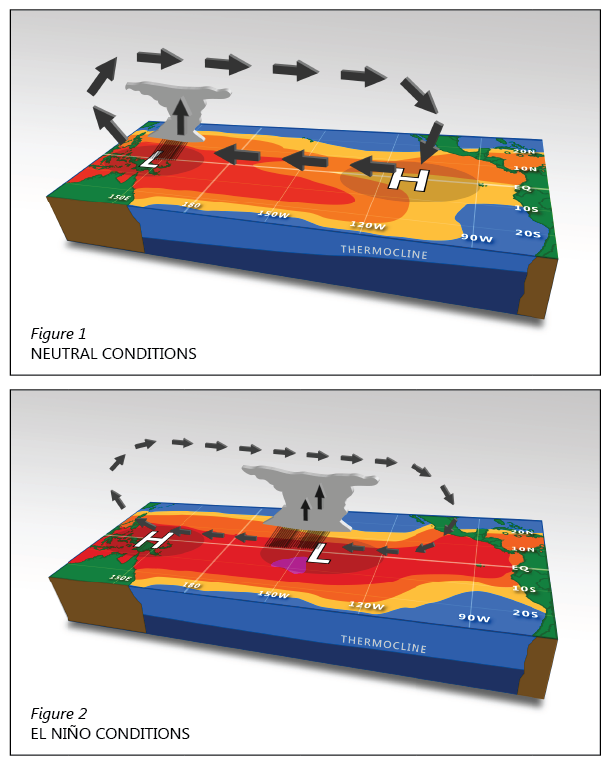

During average (non-El Niño) times, the waters of the western tropical Pacific are much warmer than in the east/central area (Figure 1). As warmer water extends out to the east during an El Niño, it warms the air, causing it to rise (lower pressure) (Figure 2). In turn, there is less rising motion (higher pressure) near Indonesia, due to the relatively cooler waters and overlying air.

Figure 1. Average state of ocean temperatures, rainfall, pressure, and winds over the Pacific during ENSO-neutral conditions. Figure 2. Generalized state of the ocean and atmosphere during El Niño conditions. NOAA image created by David Stroud.

The pressure changes influence the wind patterns. The average (non-El Niño) state of the atmosphere over the tropical Pacific features convection and rainfall over Indonesia, low-level easterly winds (the trade winds that blow from east to west), and upper-level westerly winds (Figure 1). These are the basic components of the Pacific Walker Circulation.

During El Niño, the system shifts: we see weaker trade winds over the Pacific, less rain than usual over Indonesia, and more rain than usual over the central or eastern Pacific. During some El Niño events, the trade winds along the equator even reverse, and we see low-level westerlies… but not every time. In fact, every El Niño is different, and both the ocean and atmospheric characteristics vary quite a lot from event to event–but that’s a topic for another post!

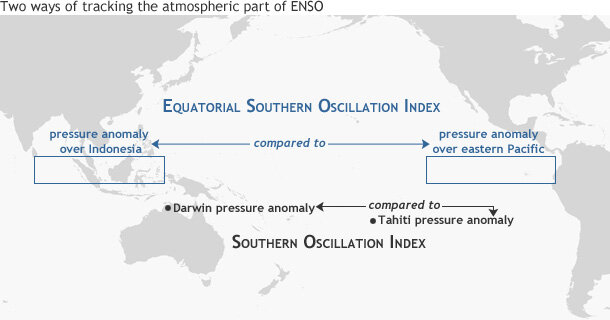

This difference from average air pressure patterns across the Pacific is measured a few different ways. One is the Southern Oscillation Index (SOI), which is based on a long record of pressure measured by two stations: one in Darwin, Australia (south of Indonesia) and the other in Tahiti (east-central tropical Pacific) (Figure 3). A negative SOI indicates Darwin’s pressure is higher than average and Tahiti’s is lower than average: El Niño conditions. (I keep saying “higher than average” because we’re not just comparing Darwin’s pressure to Tahiti’s, but rather comparing the anomalies at each. Imagine comparing the price of a gallon of water to that of a gallon of gas. A negative index is if the price of the water goes up, and the gas goes on sale. The gas may still cost more than the water, but it’s the relative changes in the two prices that matter.)

A second way we describe the air pressure anomalies over the tropical Pacific is the Equatorial Southern Oscillation Index (EQSOI). The EQSOI is based on pressure differences between two regions located on the equator (Figure 3). The SOI is monitored because it has a very long record available, stretching back to the 19th century; the EQSOI depends on satellite observations, which means it is a shorter record, but it gives a better picture of what’s happening right along the equator.

Figure 3. Two ways of measuring the Southern Oscillation: the SOI and the EQSOI. Both depend on comparing the strength of pressure anomalies in different parts of the Pacific basin. Map by NOAA Climate.gov.

As of the end of June, both the SOI and the EQSOI are at +0.2 (they have trended downward over the past few months), and the wind patterns are roughly average over the tropical Pacific, with some slight weakening of the trade winds toward the end of the month. There is increased convection in the central Pacific, but also some over Indonesia… all of which says we’re still waiting for the atmosphere to get dressed in its El Niño clothes and come out to play.

However, we think it’s likely that the atmosphere will get on board soon, and we’re still predicting El Niño, with about a 70% chance that conditions will be met in the next few months, and around an 80% chance by this fall. If you’re interested in how the ocean and atmospheric conditions are evolving, CPC has weekly updates available.

Thanks to David Stroud for his help with this post.

Comments

Misleading

RE: Misleading

Hi Dale,

Thank you for your comment. We have a previous post entitled "How will we know when El Niño has arrived" (http://www.climate.gov/news-features/blogs/enso/how-will-we-know-when-e…) that delves into this exact topic and might clear up any misunderstandings.

What is being discussed here is a declaration of the onset of El Niño conditions, which incorporates both ocean and atmospheric response (see the three criteria that must be met in the post mentioned in the prior paragraph) The 5 consecutive overlapping 3-month season standard of a positive ONI >= +0.5ºC is for establishing the lengths of a full-blown El Niño event. For that standard to be met, and since El Niño naturally includes the ocean influencing the atmosphere and vice versa, atmospheric conditions will also have been met.

RE: RE: Misleading

Subsurface temps don't seem promising... What is you take?

RE: Subsurface temps don't seem promising... What is you take?

Great observation Alec. Subsurface temps are indeed below average but overall the upper-ocean heat anomalies remain slightly above-average due to above-average subsurface temperature anomalies near the surface. This pool of near surface above-average temperature anomalies is still large enough to help get that ocean-atmosphere feedback going, even if, as this post goes into, the atmosphere has yet to fully respond.

The subsurface anomalies, though, will continue to be monitored as their influence could increase if the negative anomalies grow.

Check out the monthly discussion on ENSO that was updated yesterday.

Drier Mideast?

RE: Drier Mideast?

Phil, great question. In a previous post we delved into potential US impacts during El Nino. This image from that post as well as the top left panel in this image will help to explain why the Midwest US is dry during El Nino. You'll notice in the first image the placement of the jet stream. The more basic answer is that during El Nino this jet is displaced to the south, which means areas to the north, like the Midwest, are left high and dry while areas to the south, like the southeast US, see an increase in rainfall.

This reverses itself during La Nina as the jet stream is displaced northward leading to above-average rains (top left panel again) in the Ohio Valley and below-average rains in the southeast.

It feels like el niño already in Central America

RE: It feels like el niño already in Central America

It has certainly been dry in Nicaragua since the start of the Primera season in May. TRMM satellite rainfall estimate anomalies for the May 1-July 10, 2014 period show dryness extending across much of Nicaragua and into southern Honduras.

To take a look at what the future holds, check out our colleague's seasonal forecasts from the International Research Institute for Climate and Society (IRI). The seasonal forecasts issued in June for the July-September and August-October period shows dry conditions persisting.

El Ni-no

RE: El Ni-no

Regrettably, there is not a spanish version at this time but we will keep that in mind if our capacity changes.

American Samoa climate response to ENSO

FYI, the Aussies say: El Ni NO!

re: Recent super typhoons connection?

RE: re: Recent super typhoons connection?

The peak of the western Pacific hurricane season is July-October. The most active month is August, when an average of 6-7 tropical storms and typhoons occur. During July, an average season features 4-5 tropical storms and typhoons. This year, we have seen three such storms as of July 23rd.

El Niño favors a stronger western Pacific hurricane season, as well as stronger seasons in both the central and eastern Pacific. However, El Niño has not yet formed, and therefore has not affected the Pacific hurricane seasons to date.

No El Nino this year?

El Niño in Peru

Ask for permission

RE: Ask for permission

Yes, these are free to use. Please just credit climate.gov.

Add new comment