Double-dip La Niña

The lead character in the 2011 climate story was La Niña—the cool phase of the El Niño-Southern Oscillation—which chilled the central and eastern tropical Pacific at both the start and the end of the year. These natural cooling events have a long reach: many of the big climate events of 2011, including famine-inducing drought in East Africa, an above-average hurricane season in the Atlantic, and record rainfall in many parts of Australia, are common “side effects” of La Niña.

The La Niña that was underway at the start of 2011 was among the strongest in the historical record. By late spring, waters had warmed to “neutral” conditions. La Niña re-developed more weakly in the fall, and the tropical Pacific chilliness continued into spring of 2012.

#}Running time 0:40

This animation tracks sea surface temperature anomalies in the tropical Pacific throughout 2011. La Niña—the cool phase of the El Niño-Southern Oscillation—dominated the Pacific at the start of the year, subsided in summer, and returned in fall.

La Niña usually lowers the global average surface temperature, but you could only call 2011 “cool” in comparison to Earth’s warmest years—most of which have occurred in the past decade. With an average temperature between 0.07 and 0.16 degrees Celsius (0.13 and 0.29 degrees Fahrenheit) warmer than the 1981–2010 average, 2011 was among the 12 warmest years since historical records began 132 years ago.

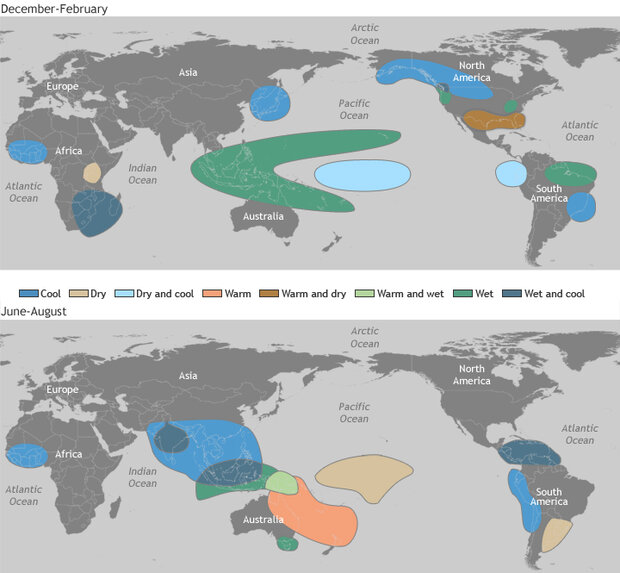

La Niña influences more than just the global surface temperature. During La Niña, the easterly trade winds in the Pacific strengthen; tropical rainfall is suppressed in the eastern Pacific and enhanced in the western Pacific; the Pacific jet stream meanders farther north than usual. Many of the big climate events of 2011 were classic examples of the long-distance connections between La Niña and seasonal climate in places around the world.

Certain climate patterns are more likely during La Niña years, including unusually wet summers in Australia, and warm, dry winters in the U.S. South. Maps adapted by climate climate.gov team, based on originals by NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center. Large version of December-February impacts. Large version of June-August impacts.

At the top of the list was a devastating drought in East Africa that, combined with social and political factors, led to food insecurity in parts of Ethiopia and Kenya and outright famine in Somalia. Rainfall in the Horn of Africa is sharply seasonal, with one rainy season in the fall (September-December) and another in spring (March-May). The fall rains are closely tied to La Niña and El Niño, with La Niña frequently suppressing rain.

With La Niña in place at the end of 2010, the fall rainy season in East Africa failed to deliver even a quarter of the normal moisture to the region. The subsequent failure of the 2011 spring rains—which recent research has connected to the long-term warming trend in the Pacific—pushed the region into a drought that the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization described as the worst in 60 years.

South of the equator, however, Australia was getting soaked for the second year in a row. The annual average rainfall was very-much above average for the majority of the country in 2011, and many places received record rainfall, including large parts of Northern Territory and Western Australia. The early part of the year—during the stronger La Niña—brought record-breaking rain to places farther east, including much of New South Wales and Victoria.

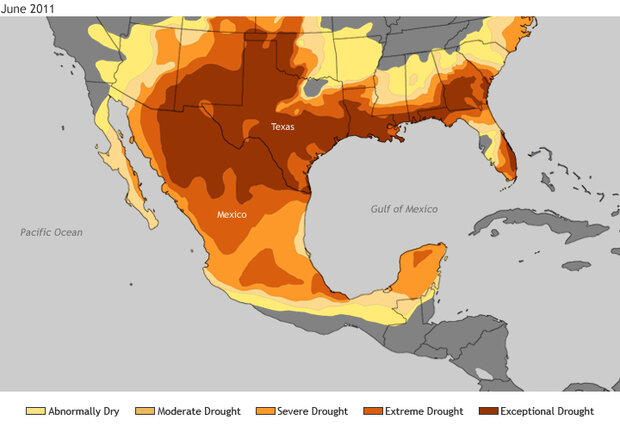

Further demonstrating the ability of La Niña to tip a region’s climate toward its natural extremes, La Niña likely contributed to the continuation of historic drought in northern Mexico and the southern United States in 2011. In some parts of Texas, New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Louisiana summer heat conspired with the exceptional dryness to break records for cumulative drought impacts on water storage, including reservoirs and ground water. Across the border, 85 percent of Mexico was affected by some level of drought in June, and the country suffered its worst forest fire season in history, with an estimated 2.4 million acres burned.

In late June, severe to exceptional drought spread across a wide portion of the southern U.S. and northern Mexico. Maps by climate.gov team, based on data from the North American Drought Monitor project.

In general, the strongest impacts of La Niña or El Niño events are felt in fall and winter. But the summer of 2011 was sandwiched between two La Niña events, which meant that the 2011 Atlantic hurricane season couldn’t escape La Niña’s long reach. For the second year in a row, the Atlantic basin experienced above-average activity, which is a common side effect of La Niña.

As 2011 drew to a close, La Niña kept its grip on the Pacific. That the 2011 global average surface temperature ranked so near the top ten warmest years on record despite the “double-dip” influence of La Niña is one of many indications of long-term climate warming. Including the 2011 temperature, the rate of warming since 1971 is now between 0.14° and 0.17° Celsius per decade (0.25°-0.31° Fahrenheit), and 0.71-0.77° Celsius per century (1.28°-1.39° F) since 1901.

Article by Rebecca Lindsey. Reviewed by Deke Arndt and Jessica Blunden. The full State of the Climate in 2011 report is available as a pdf from the National Climatic Data Center.