Climate.gov tweet chat: Talk El Niño and La Niña with the ENSO bloggers

The world of climate phenomena is cluttered with all sorts of oscillations—natural back-and-forth swings between two states of the climate system. The acronyms experts use for these oscillations—PDO, PNA, AO, NAO, MJO—can make it seem like scientists are speaking a foreign language. But if there is one oscillation that transcends that acronym gobbledygook, it’s El Niño and La Niña: the warm and cool phases of the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO).

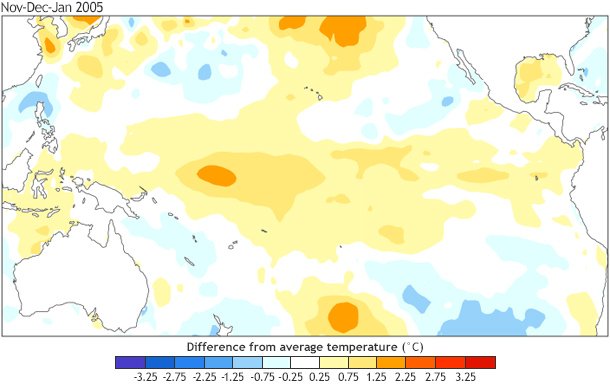

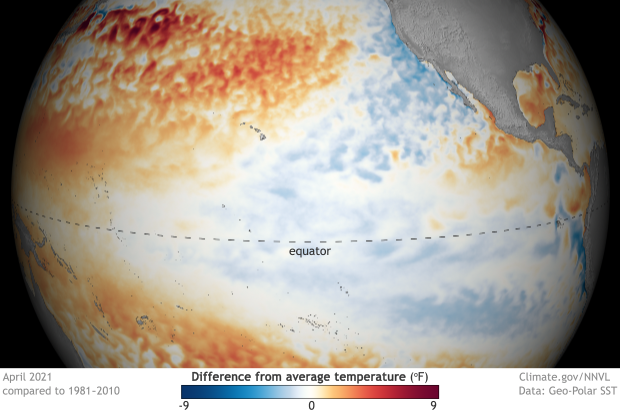

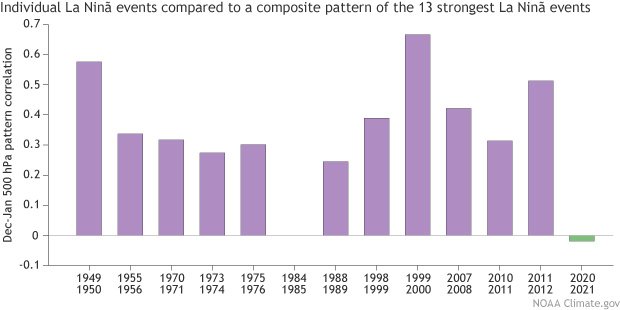

Sea surface temperature anomalies across the ENSO regions of the Pacific Ocean in December 2020, when La Niña was in progress. Reds indicate areas where sea surface temperatures were warmer than average, and blue colors indicate areas where sea surface temperatures were cooler than average. NOAA Climate.gov image from our Data Snapshots collection.

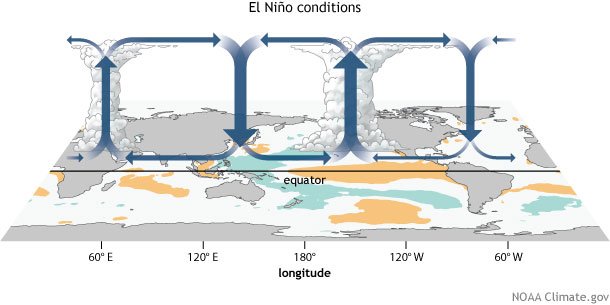

El Niño and La Niña were named for patterns of ocean temperatures across the tropical Pacific Ocean: large areas seesaw back and forth from warmer than average to cooler than average. The ocean patterns then disrupt the large-scale weather patterns in the tropical atmosphere. These phases occur every two to seven years and can cause predictable disruptions to seasonal average temperature, precipitation, and winds—not only in the tropical Pacific, but around the world.

Droughts, floods, and tropical cyclones are just a few examples of the sort of weather and climate extremes that can be made more or less likely during ENSO events. ENSO events and their influence on the climate can also be predictable months in advance, giving communities a heads up to plan for potential climate disasters. But there is still a lot left to learn about ENSO, including how far ahead we can hope to predict it, why some events are strong and others weak, and how it might change in a warmer climate.

On Thursday, June 3 from 1;00 to 2:00 p.m. Eastern, join Climate.gov ENSO Bloggers Michelle L’Heureux, Emily Becker, Nat Johnson, and Tom Di Liberto for a tweet chat all about El Niño and La Niña. We know you’ll have plenty of questions!

Michelle L’Heureux—Meteorologist at NOAA NWS Climate Prediction Center and ENSO team lead

Emily Becker—Associate Director of the University of Miami Cooperative Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Studies (CIMAS)

Nat Johnson—Scientist at NOAA’s Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory

Tom Di Liberto—Climate scientist for NOAA’s Climate.gov at the Climate Program Office, and social media manager for NOAAClimate.

What: Tweet chat — tweet your questions @NOAAClimate and use the hashtag #ClimateQA

- When: June 3, 1:00 — 2:00 p.m. EDT

- Where: https://twitter.com/NOAAClimate

Can’t make the chat? Return to this page in coming weeks; we will update this page with a selection of questions and answers from the discussion.

ENSO Tweet Chat transcript

NOAA Climate.gov: Welcome to the ENSO, El Niño and La Niña Tweet Chat! For the next hour, experts Climate.gov's ENSO blog will be here to answer any questions you may have about El Niño and La Niña. Make sure to tag your questions with #ClimateQA

Introductions

NOAA Climate.gov: Now to introduce our experts. First up is Michelle L'Heureux. Michelle is a Meteorologist at @NWSCPC, ENSO team lead, and the fearless leader of the Climate.gov ENSO Blog. https://www.weather.gov/careers/physical-science-michelle-LHeureux

NOAA Climate.gov: Emily Becker is the associate director of the University of Miami Cooperative Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Studies. When she’s not writing for the ENSO Blog or researching seasonal climate prediction, you can find her swimming, or in her garden. #ClimateQA.

NOAA Climate.gov: Nat Johnson is a meteorologist at the Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory in Princeton, New Jersey. His work focuses on subseasonal to seasonal climate prediction, which means that ENSO is never far from his mind. https://gfdl.noaa.gov

When he isn’t thinking about climate science, he’s probably running, watching his beloved Duke Blue Devils, managing his pathetic fantasy baseball team, or jamming out on his guitar. #ClimateQA

NOAA Climate.gov: Tom Di Liberto (@TDiLiberto) is a meteorologist at @NOAA’s Climate Program Office and Climate.gov and the social media manager for the NOAAClimate accounts on Twitter/Facebook/Instagram. Yup, that means he’s the person behind all of the tweets you see here.

When he’s not science communicating to the world, Tom is likely chasing around his kids, performing comedy or simply looking at the clouds. Seriously, clouds are really cool.

Question

Dr. John Callahan: What are the physical mechanisms that bring about the end of ENSO, or specifically El Mono? Is it mostly underlying poleward ocean currents, or synoptic wind forcing, or something else entirely?

Answer

ENSO Blog Team: Great Question! Largely, it is delayed processes in the ocean that cause the end of ENSO events, but not exclusively. Sometimes we see shifts in the wind first... but it's a coupled system so it's hard sometimes to see the primary driver.

Sometimes, for instance, like during an MJO event, the shifts in the wind start pushing the ocean a certain direction.

Ultimately, though, an El Nino ends with the poleward discharge of ocean heat away from the equator. See this ENSO Blog post for more info. https://www.climate.gov/news-features/blogs/enso/life-and-death-el-ni%C3%B1o

Temperature anomalies (departures from normal) averaged from the surface to 300 meters (or 984 feet) below the surface of the Pacific Ocean. Red shading shows where temperatures are above-average and blue shading shows where the temperatures are below-average. Animation by climate.gov using pentad (5-day) averaged data from NCEP GODAS.

Footnote 3 in our most recent post on double dip La Nina goes into this a bit more.

https://www.climate.gov/news-features/blogs/enso/double-dipping-why-does-la-ni%C3%B1a-often-occur-consecutive-winters

Question

Tweet: I would like to ask if: 1. El Niño Modoki can affect Maritime Continent? 2. Will we see the same magnitude of prolonged & intense drought + haze during El Niño years in Maritime Continent like 2015/16 or will it be more intense in the future?

Answer

ENSO Blog Team: El Nino modoki tend to be weaker El Ninos which means that their impacts in the Maritime Continent are weaker. Here's a post looking at different "flavors" of ENSO. https://www.climate.gov/news-features/blogs/enso/enso-flavor-month

Sea surface temperature anomalies (departures from average) during November 2004–January 2005. Data based on OISSTv2 and using 1981–2010 base period.

But by definition El Nino Modoki is an El Nino. And El Ninos affect the Walker Circulation in the tropics, affecting the Maritime Continent. https://www.climate.gov/news-features/blogs/enso/walker-circulation-ensos-atmospheric-buddy

Your other question: There is evidence that ENSO-related droughts and floods will increase under global warming, so strong El Ninos like the 2015/16 event may induce stronger maritime continent droughts.

ENSO Outlook Interlude

NOAA Climate.gov: For those wondering, the latest ENSO outlook released in May says that La Nina is over! There is a ~67% chance that neutral conditions will continue through summer. The ENSO forecast for the fall is less confident.

https://climate.gov/news-features/blogs/enso/may-2021-enso-update-bye-now-la-ni%C3%B1a

You might be thinking "May?...that was a whole month ago!" and you'd be right! The next ENSO outlook comes out next week on June 10

[Editor Note: This is obviously dated but you can still find the most recent ENSO Outlook via the link below]

https://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/products/analysis_monitoring/enso_advisory/ensodisc.shtml

Question

Tweet: Another question! 1. Is there any direct correlation between MJO propagation & El Niño/La Niña? 2. Can MJO directly affect the status of El Niño or La Niña to be strong/moderate/weak?

Answer

ENSO Blog Team: Good question. There is at least one study suggesting that different MJO types with different propagation characteristics could be affected by El Nino and La Nina. https://advances.sciencemag.org/content/5/7/eaax0220

Question

Marybeth Arcodia: Hi ENSO blog team Waving hand As the climate continues to warm, how do you expect El Niño and La Niña conditions and U.S. impacts to change?

Answer

ENSO Blog Team: There may be changes in ENSO itself, which is complicated (Tom's post). But there is no doubt that ENSO related impacts will be influenced by climate change (droughts could be more severe, rainfall events more intense) https://www.climate.gov/news-features/blogs/enso/enso-climate-change-headache

It's definitely an active area of research and a topic we've covered a lot on the ENSO Blog. Here is another post looking at US impacts.

https://www.climate.gov/news-features/blogs/enso/changes-enso-impacts-warming-world

SHOUTOUT

NOAA Climate.gov: We obviously love folks reading our Climate.gov ENSO Blog, but we did want to give a shout out to Seasoned Chaos @seasonedchaos from the University of Miami RSMAS. Great and interesting posts on climate.

Question

Jose Molina: We have many studies on teleconnections btwn ENSO & events of Prcp, Runoff, etc., but not with Fog, which will be the only water source under #ClimateChange for people worldwide Thoughts #ClimateQA on ENSO-driven future Fog events?

https://youtu.be/rKguOJFXxPc

Answer

ENSO Blog Team: We're a little foggy on that tbh. It'll depend where you are, but if ENSO changes, ENSO-related ocean temperature changes will change the incidence of fog. Worth more research! Also a good topic for guest blog perhaps! Contact us if that is your area of expertise.

Question

Brandon: How will climate change directly affect El Niño or La Niña? Will it increase/decrease it’s intensity? Increase/decrease it’s frequency?

Answer

ENSO Blog Team: That is a big and important question, and a very active area of research. The best answer is that it is complicated. We tried to cover it as best we could in several posts. Head to our Index page for the ENSO blog for our climate change posts. https://www.climate.gov/news-features/blogs/enso/index-page-enso-blog-posts#hide7

Question

Kayla Besong: Regarding the spring predictability barrier, is there any expectation for how the barrier may change in the future? Such as how it may increase/decrease with 1) a changing climate 2) improved statistical tools (such as ML/AI) or 3) other forecasts of opportunity?

Answer

ENSO Blog Team: Really good question.... we don't know of many research papers on this. There aren't many initialized models that are run on future climate scenarios. A good research topic...

Question

Croix Baker: Do we have ways of inferring what ENSO was like in previous centuries? Are we able to tell if a time period had stronger phases than others?

Answer

ENSO Blog Team: You bet! Scientists can look at fossil coral, tree rings, ice/sediment cores to reconstruct the ENSO for thousands of years. Here are a couple of posts looking into that.

https://www.climate.gov/news-features/blogs/enso/bittersweet-victory-el-ni%C3%B1o-chaser

https://www.climate.gov/news-features/blogs/enso/can-volcanic-eruptions-cause-el-ni%C3%B1o-maybe-maybe-not

The author, Kim Cobb, installing a Conductivity-Temperature-Depth (CTD) sensor on a healthy coral reef at Kiritimati Island. Photo credit: Pamela Grothe.

Question

Tweet: Why did La Nina not produce (high) precipitation in late December/January for Oregon? Wasn't there some countervailing force over Newfoundland/Greenland or something? Did that phenomena have a name?

Answer

ENSO Blog Team: Good question.... sometimes impacts don't match the seasonal expectation (why our forecasts are given as probabilities). Nat did attempt to explain what was going on with winter climate over N. America here: https://www.climate.gov/news-features/blogs/enso/did-northern-hemisphere-get-memo-years-la-ni%C3%B1a

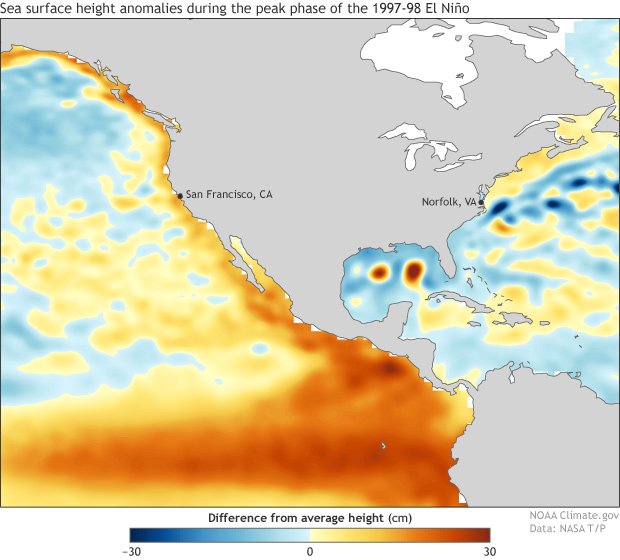

Pattern correlations between the individual La Niña and average La Niña December – January 500 hPa geopotential height anomalies north of 15°N for the 13 strongest La Niña episodes since 1950. Positive values indicate at least some degree of pattern matching, with 1 indicating a perfect match, and negative values indicate a mismatch between the two patterns. NOAA Climate.gov figure with NCEP/NCAR Reanalysis data obtained from the NOAA Physical Sciences Laboratory.

Question

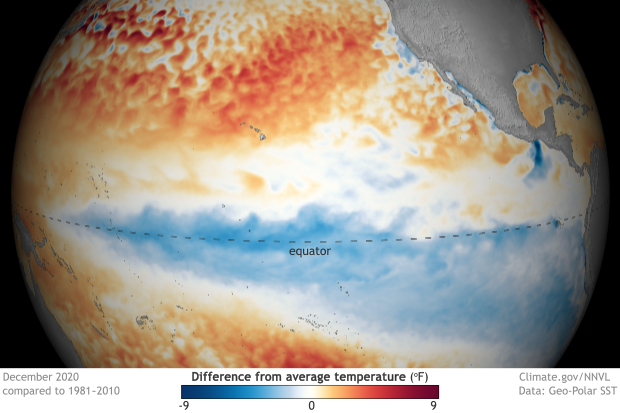

Victoria Schoenwald: Hi ENSO blog team! Will changes in ENSO due to climate change affect sea level rise across the U.S.? #ClimateQA

Answer

ENSO Blog Team: Hi Victoria! Complicated question... ENSO does have an impact on coastal flooding

Of course, climate change is causing sea level rise. So I would expect that ENSO-related flooding would be enhanced in the future, due to increased background sea level.

Sea surface height anomalies during the peak phase (December 1997-February 1998) of the 1997-98 El Niño. The sea surface height (in centimeters) is estimated from TOPEX-POSEIDON altimeter data. Image is from Ben Kirtman and was modified by climate.gov.

An ENSO Goodbye

NOAA Climate.gov: And so concludes our ENSO Tweet chat. Thanks again to our experts over at the ENSO Blog for spending some time with us today. If you want them back in the future, let us know! And if you still have questions, feel free to ask them! #ClimateQA Climate.gov/enso