Climate Variability: Oceanic Niño Index

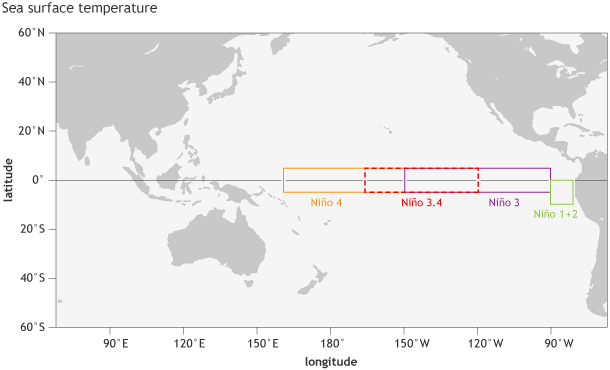

The Oceanic Niño Index (ONI) is NOAA's primary indicator for monitoring the ocean part of the seasonal climate pattern called the El Niño-Southern Oscillation, or “ENSO” for short. (The atmospheric part is monitored with the Southern Oscillation Index.) The ONI tracks the running 3-month average sea surface temperatures in the east-central tropical Pacific between 120°-170°W, near the International Dateline, and whether they are warmer or cooler than average.

Location of the parts of the tropical Pacific used for monitoring sea surface temperature. The sea surface temperature in the Niño3.4 region, spanning from 120˚W to 170˚W longitude, when averaged over a 3-month period, forms NOAA’s official Oceanic Niño Index (the ONI). NOAA Climate.gov image by Fiona Martin.

NOAA considers El Niño conditions to be present in the ocean when the ONI in that area, known as the Niño-3.4 region, is +0.5 or higher, meaning surface waters in the east-central tropical Pacific are 0.5 degrees Celsius (0.9 degrees Fahrenheit) or more warmer than average. Oceanic La Niña conditions exist when the ONI is -0.5 or lower, indicating the region is 0.5 degrees Celsius or more cooler than average.

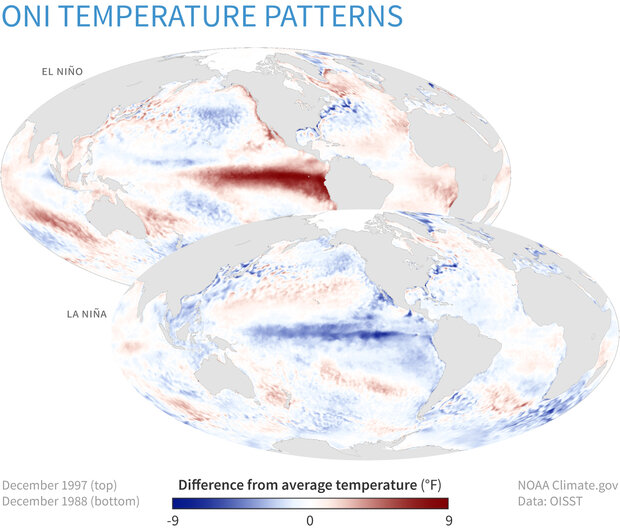

Sea surface temperature across the tropical Pacific Ocean in December 1997 (top), during a strong El Niño, and in December 1988 (bottom) during a strong La Niña. The ONI only tracks the temperatures in the Niño3.4 region, but during strong events, the entire central and eastern tropical Pacific will generally become warmer or cooler than average. Maps by NOAA Climate.gov, based on data from NOAA's Physical Science Lab.

El Niño brings warmer-than-average waters to the central and eastern tropical Pacific, sometimes all the way to the coast of South America. At the surface, the prevailing easterlies (the trade winds) slow down, or sometimes even reverse. Over the warm waters in the central-east tropical Pacific, rainfall increases, but it decreases over Indonesia and the western Pacific.

La Niña brings cooler-than-average waters to the central and eastern tropical Pacific, again, sometimes all the way to South America. The prevailing easterlies (the trade winds) intensify. over the cooler-than-average waters of the central-east tropical Pacific, rainfall decreases, but it increases over Indonesia and the western Pacific.

Neutral means neither El Niño nor La Niña conditions are present in both the ocean and the atmosphere. Sometimes "neutral" genuinely means that conditions in the ocean and the atmosphere are near average. But other times, the conditions for El Niño or La Niña have actually been met in the ocean, but not in the atmosphere. This state is also considered to neutral because unless the ocean and atmosphere are fully in sync (experts say "coupled"), ENSO can't reach its full, climate-disrupting potential.

Monitoring ENSO

ENSO is a seasonal-scale climate pattern, not something that changes from day to day or week to week. To calculate the ONI, scientists from NOAA's Climate Prediction Center calculate the average sea surface temperature in the Niño 3.4 region for each month, using in-ocean measurements from a variety of sources, including autonomous floats, moored buoys, and ship cruises. They blend the observations into a single monthly average and then average it with values from the previous and following months. This running three-month average is compared to a 30-year average. The observed difference from the average temperature in that region—whether warmer or cooler—is the ONI value for that 3-month "season."

ENSO beyond the tropics

ENSO shifts irregularly back and forth between El Niño and La Niña every two to seven years. Each phase triggers predictable disruptions of temperature, precipitation, and winds in the tropical Pacific Ocean. These changes disrupt the large-scale air movements in the tropics, which triggers a cascade of global side effects. During El Niño winters, northwestern North America is more likely to experience warmer-than average temperatures and the southeastern U.S. is more likely to receive more rain than average. La Niña often brings the opposite. In addition, La Niña conditions are generally more favorable for the formation of Atlantic hurricanes. Because the mid-latitudes are farther removed from the "main event" in the tropical Pacific, however, the impacts in the United States are not as consistent, and they can be overpowered by other climate influences.

Further Reading

- Climate.gov ENSO Blog

- Frequently asked questions about El Niño and La Niña

- NOAA's ENSO alert system

- Climate Prediction Center's ENSO Cycle Page, Accessed December 10, 2009.

- ENSO-tagged posts at International Research Institute for Climate and Society. Accessed October 2, 2009.