Low snow drives Iditarod north for third time

For only the third time since its inception in 1974, Alaska’s famous Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race kicked off in Fairbanks—250 miles north of the traditional start in the southern coastal city of Anchorage. Iditarod Trail Committee officials announced the decision in February, citing “poor conditions of critical trail areas in the Alaska Range,” as the reason behind the shift north.

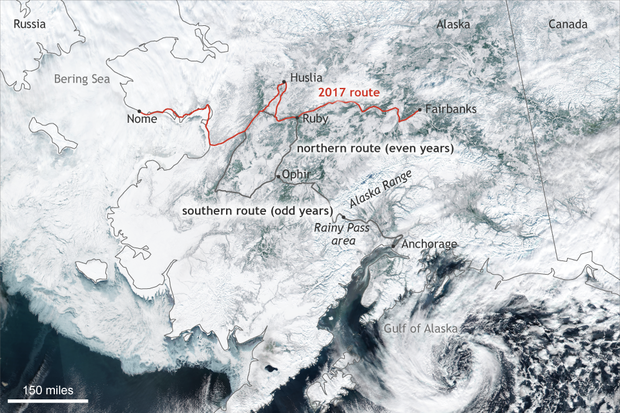

Alaska on March 1, 2017, with the traditional and alternate routes of the Iditarod race included. Climate.gov image based on visible and infrared data from the NASA/NOAA Suomi-NPP satellite.

The image above shows the traditional Iditarod trail routes in black with this year’s route in red. The routes are overlaid on a satellite image of the state captured on March 1, 2017. Normally, mushers start the race out of Anchorage and travel north-northwest through the Alaska Range. Once in the central interior, the trail splits at the town of Ophir, alternating between a northern route in even years and a southern route in odd years. This year’s race mirrors 2015’s, with teams leaving Fairbanks and not intersecting with the traditional route until the town of Ruby. They make an additional detour north to the town of Huslia, which marks the halfway point of the 1,049 mile race.

Each time the race has been forced to re-route—the other two years were 2003 and 2015—it was due to lack of snow and unfrozen rivers, streams, and ponds in the low-elevation passes of the Alaska Mountain Range. Earlier this year, local news outlets reported low snow in Rainy Pass and the Dalzell Gorge, a “notoriously perilous stretch” of the traditional trail located on the north side of the Alaska Range.

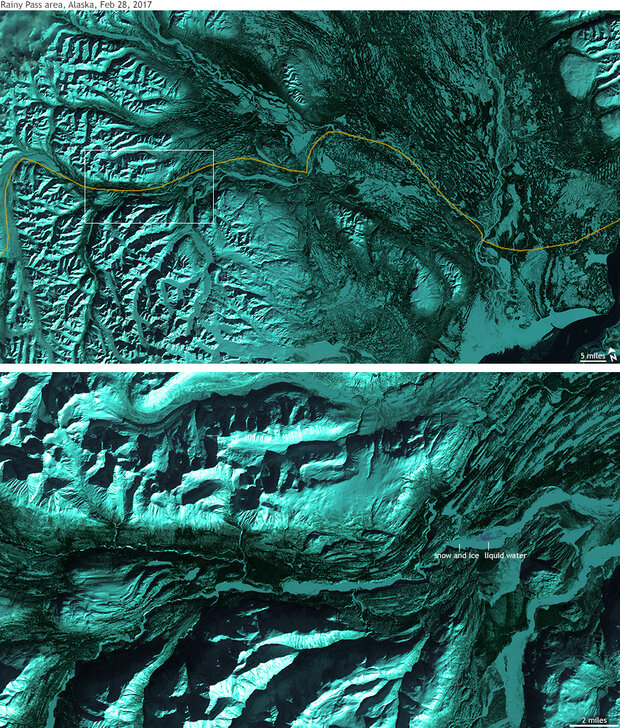

This infrared-enhanced satellite image reveals one of the hazards that race teams would have faced through the low-elevation passes of the Alaska Range: on the river, patches of ice so thin that the darker blue of liquid water below the surface is visible. The approximate path of the traditional Iditarod route is marked with a yellow line. Snowy surfaces are bright blue, vegetation is green, and liquid water is very dark blue. NOAA Climate.gov image based on Landsat satellite data on February 28, 2017.

This stretch of trail has given mushers heartburn before. In 2014, the trail was down to bare rock in some places. Those conditions resulted in injuries, and several mushers—even some veterans—were forced to drop out after crashes.

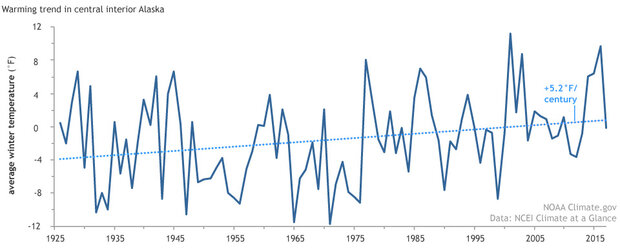

It’s not a coincidence that all three re-routes of the Iditarod have occurred in the more recent decades of the race’s history. The December-February average temperature for the state as a whole is warming by 4.2 degrees F per century.

Winter temperatures in Alaska’s central interior, which includes the northern passes of the Alaska Range, are warming at a rate of 5.2 degrees F per century. To put that into perspective: that’s more than double the rate of winter warming in the lower 48 states (2.2 degrees F/century).

Winter (December-February) temperature in U.S. Climate Division 3 (central interior region) since 1925 (dark blue line) along with the warming trend (dotted blue line). NOAA Climate.gov graph, based on data from NCEI’s Climate at a Glance.

Record warm temperatures were what pushed the race northward in 2003 and 2015—the state’s 3rd warmest and 5th warmest winters on record, respectively. Even 2014, which caused the mushers trouble in Rainy Pass, was the state’s 8th warmest winter on record. But that wasn’t the case this year. This winter has been climate “normal” for much of Alaska; it was only the 32nd warmest winter since records began. But according to Rick Thoman, climate services director for the Alaska region of the National Weather Service, some finicky upper-level wind patterns shut the Rainy Pass area out of the snow bounty seen elsewhere in the state.

Even if this winter was an average one for Alaska, it followed a record-shattering year for the state. In 2016, many Alaskan communities recorded their highest average temperatures ever: including the traditional Iditarod bookends of Anchorage and Nome. Anchorage’s average temperature in 2016 was a record-breaking 4.4 degrees F above normal and Nome’s was a record-breaking 5.1 degrees F above normal.

As climatologist Deke Arndt has blogged about before, one global warming rule of thumb is that colder places are generally warming faster than already warm places. Alaska is our nation’s poster child for that rule, thanks to the process of “Arctic amplification” of climate change. As temperatures rise and sea ice and snow melt, the darker water and land surfaces reflect less incoming sunlight, accelerating warming.

The impacts extend to things more consequential than the Iditarod. Permafrost is thawing and collapsing, undermining roads and other infrastructure--even whole towns. Sea ice declines have left coastlines exposed to battering waves and severe erosion. Insect outbreaks and fires are becoming more extensive. The behavior of animals that sustain the traditional hunting patterns of native peoples is changing. Iditarod aside, Alaska is racing toward a very different climate future.