As sea ice retreats, more ship traffic is entering the Arctic high seas

Details

In last year’s Arctic Report Card, experts provided indirect evidence that ship traffic is increasing in the Arctic: record amounts of foreign trash and marine debris like abandoned fishing gear are washing up in Bering Sea communities, and the underwater soundscape is getting louder. An essay in the 2022 Arctic Report Card reports direct evidence that ship traffic is increasing as sea ice dwindles—not just in near-shore, territorial waters of Arctic coastal countries, but increasingly, in the high seas of the Central Arctic Ocean.

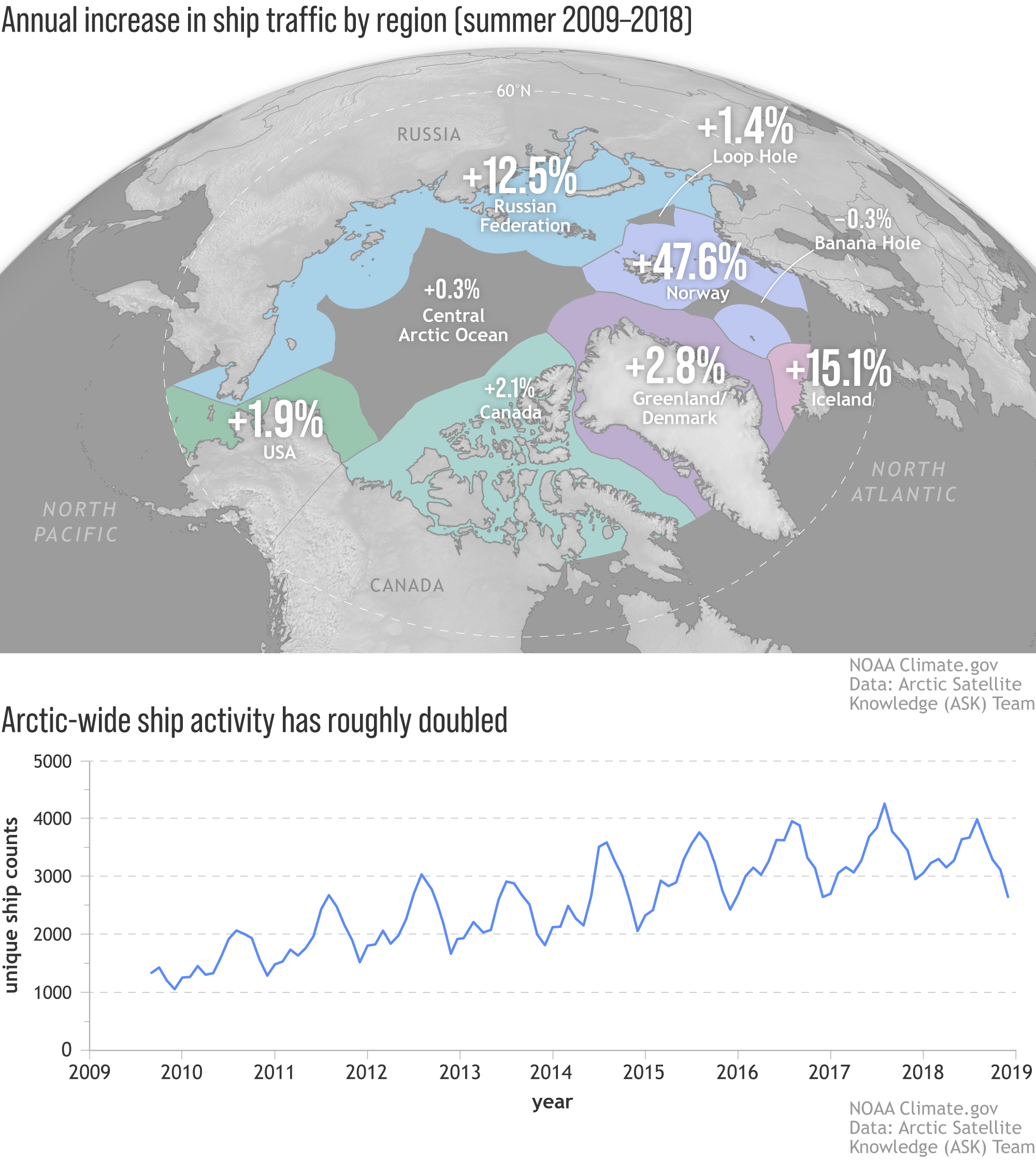

This map shows the percent increases between 2009 and 2018 in summer ship traffic within the boundaries of the exclusive economic zones of the 6 countries with territorial waters north of the Arctic Circle plus the Bering Strait Region—Canada, Denmark/Greenland, Iceland, Norway, Russia, and the United States—as well as the areas beyond national jurisdictions in the Arctic high seas under international law: the Central Arctic Ocean, Banana Hole, and Loop Hole. Bold numbers show places where the summer increase is statistically significant compared to low year-to-year variability. Norway stands out, with increases of nearly 50 percent, but Iceland and Russia also saw substantial increases.

Perhaps more surprising, the authors reported that several areas have seen significant increases in winter ship activity, meaning human presence in the Arctic is increasing year-round. The graph bears this out. It shows total monthly ship activity Arctic-wide over the same period as the map. Not only do the summer peaks march steadily upward, but winter lulls get less quiet over time. Overall, activity has roughly doubled over the decade. Data are based on satellite automatic identification system (S-AIS), which continuously broadcast ship locations to ensure maritime safety as required by the International Maritime Organization.

Increases in Arctic ship traffic will have profound impacts on the region and its people. Sea ice retreat will open avenues for maritime tourism, fishing, cargo transport, marine resource extraction, and scientific exploration. But ship traffic also poses significant risks: oil and chemical spills; trash; interference with subsistence hunting; noise pollution; air pollution with “black carbon” (soot and other dark particles produced when fossil fuels are burned); over-fishing; ship strikes of marine mammals; and introduction of invasive species from ballast. There’s also the risk to ships and crews themselves, in the event that people begin entering the Arctic without polar-class ships and experience in icy waters.

The authors of the essay point out that these impacts will fall most heavily on Arctic Indigenous communities, whose traditional activities have allowed them to live in the Arctic “in a resilient manner in the face of ecosystem changes across millennia.” The essay notes that ship traffic into the Central Arctic Ocean is increasing most significantly from the Pacific sector—through the Bering Strait—which means Alaska native communities in that area and along the Indigenous corridor north of the Aleutian Islands may be especially vulnerable to the negative impacts of increasing ship activity in the Arctic Ocean.

References

Berkman, P.A., G. J. Fiske, D. Lorenzini, O. R. Young, K. Pletnikoff, J. M. Grebmeier, L. M. Fernandez, L. M. Divine, D. Causey, K. E. Kapsar, and L. L. Jørgensen. (2022). Satellite Record of Pan-Arctic Maritime Ship Traffic. In Arctic Report Card: Update for 2022.