Mountain air becoming less brisk, more high-elevation observations needed

Details

If you grew up without air conditioning near a mountain range, you know that a good way to beat the summertime heat is to head for the hills. But climate change appears to be making mountain air less brisk more quickly than scientists previously thought. Accelerated warming at high elevations could have serious consequences for water supplies and alpine plants and animals.

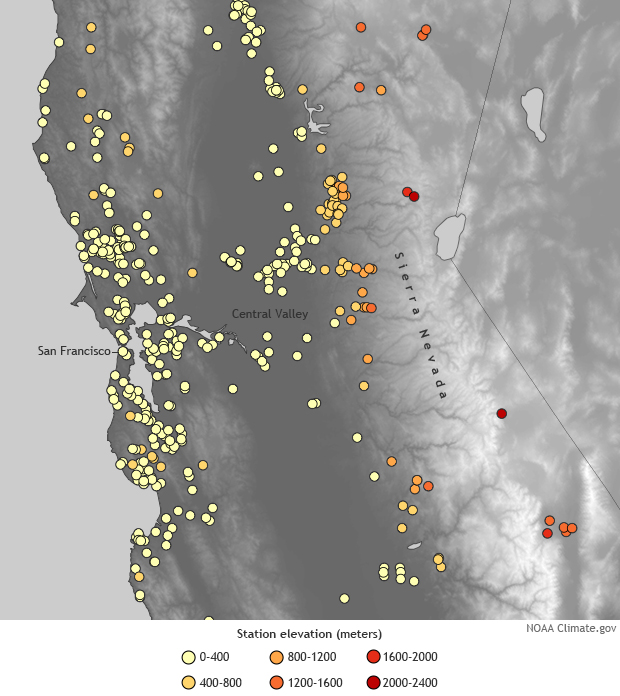

Multiple lines of evidence suggest that high-elevation areas are warming faster than other parts of the globe, but just how much faster—or how much variability exists from place to place—scientists can't say. The lack of certainty about high-elevation warming is down to the worldwide scarcity of high-elevation weather stations. This map illustrates the location and elevation of all stations that are part of the Global Historical Climatology Network in California.

The lower elevations around San Francisco (and Los Angeles, visible in the large image) have many stations, while the higher elevations of the Sierras to the east have very few.

In a new paper in Nature Climate Change, scientists reviewing the availability of high-elevation climate data wrote that out of more than 7,000 weather stations in the Global Historical Climatology Network, only 3% are situated more than 2,000 meters (6,500 feet) above sea level, and less than 1% are above 3,000 meters (10,000 feet). Above 5,000 meters (16,000 feet), temperature records longer than 20 years are "simply nonexistent."

The long-term weather station records that do exist show a worrisome trend. The weather stations that have been built on the Tibetan Plateau show that over the past 20 years, temperatures above 4,000 meters (13,000 feet) have risen almost 75% faster than temperatures below 2,000 meters (6,500 feet).

The location and density of climate observing stations is a function of human settlement patterns. We have more stations, with longer histories, for lower elevations because that is where people live for the most part—near coasts, along rivers, in fertile valleys and plains where agriculture is easier. Mountainous areas are difficult to reach, their harsher weather is tougher on equipment, and they can have many different microclimates from slope to slope.

But even if people don’t live there in high densities, mountains are more than just summertime vacation spots. Around the world from California, to New Zealand, to India, mountains are the world's "water towers." For millions of people, mountain snowpack is a nature-made reservoir, with summer releases that keep water flowing to lower elevations at the hottest, driest time of year.

In addition to supplying water to millions of people, mountains provide cooler habitat for temperature-sensitive species of plants and animals. High-elevation species that must migrate upslope in a warming climate may soon be left with nowhere to go.

This research was conducted by a team of scientists as part of the Mountain Research Initiative, a mountain global change research effort funded by the Swiss National Foundation. Two of the authors are with NOAA’s Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences, part of NOAA’s Earth System Research Laboratory. Caption By MIchon Scott. NOAA Climate.gov map based on GHCN (V3) data from the National Center for Environment Information.

Links

Mountain Research Initiative EDW Working Group. (2015). Elevation-dependent warming in mountain regions of the world. Nature Climate Change, 5(5), 424–430. http://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2563