For Europe and central Asia, winter plays catch-up in February

Details

For Europe, the first two calendar months of winter were mild. In December and most of January, temperatures averaged several degrees warmer than normal. As if to make up for lost time, however, exceptionally cold weather arrived in late January and remained firmly entrenched for weeks, causing many deaths as well as transportation chaos, according to news reports.

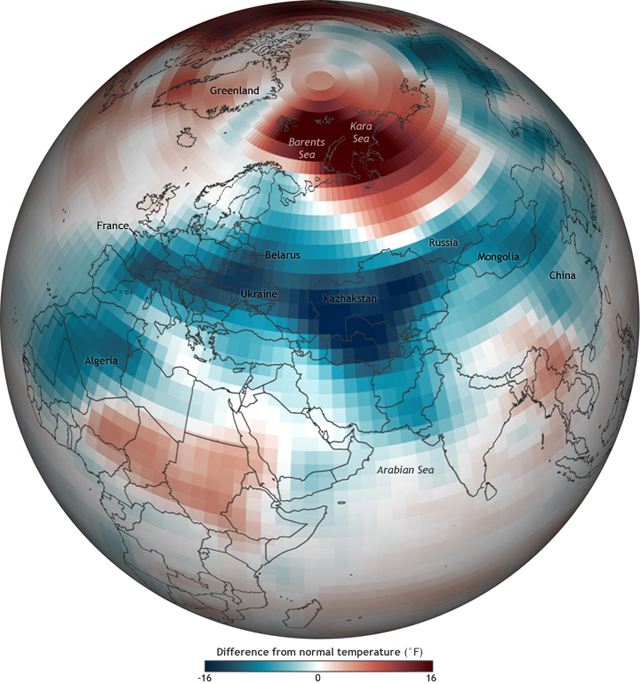

This map shows the extent and intensity of the cold snap across Europe and central Asia in February 2012. (Map includes data through February 25.) Places where temperatures were up to 16 degrees Fahrenheit colder than normal are deep blue, while places that were up to 16 degrees F warmer than normal are deep red. The "normal" February temperatures are based on data from 1981–2010.

In Europe, the most unusually cold temperatures settled over the East, especially Belarus and Ukraine, with an additional strong cold spot over southern France. Farther east, the cold anomalies were even more intense over Kazakhstan, and to its south, (not labeled) Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan. Colder than normal temperatures extend across Asia and even down into North Africa.

Several natural climate patterns can influence winter weather in the Northern Hemisphere. Among the strongest influences on European winters is the Arctic Oscillation. Winters are often milder than normal when the Arctic Oscillation is in its positive phase and cooler than normal when the pattern is in its negative phase.

The Arctic Oscillation flip-flopped twice so far this winter. The pattern was in its positive phase through mid-January, favoring mild conditions, and in its negative phase for the next several weeks, contributing to the chilly conditions in Europe. In mid-February, the Arctic Oscillation flipped back to its positive phase. While the cold conditions across Europe began to lose their grip later in the month, the Arctic blast certainly left its fingerprint on the monthly average temperature anomalies.

The cold in central Asia was matched by unusual warmth in the Kara and Barents Seas of the Arctic, likely connected to strong, steady winds from the south and west that have pushed sea ice deeper into the Arctic, leaving more open water than usual. Whatever warmth southerly winds might have brought, the lack of ice itself is probably contributing to the much warmer than normal temperatures. Sea ice insulates the ocean, preventing heat from the ocean from being lost to the air.

"Since that area is normally ice-covered," explains Walt Meier of the National Snow and Ice Data Center, "the air temperatures would usually be well below freezing at this time of the year. The open water will keep the surface temperatures essentially at the freezing point and the atmosphere above not much cooler."

Near-freezing might not sound warm, but for the Arctic in the dead of winter, it's warmer than normal.

Related