Deep layer of hurricane-friendly water still present in Caribbean Sea

Details

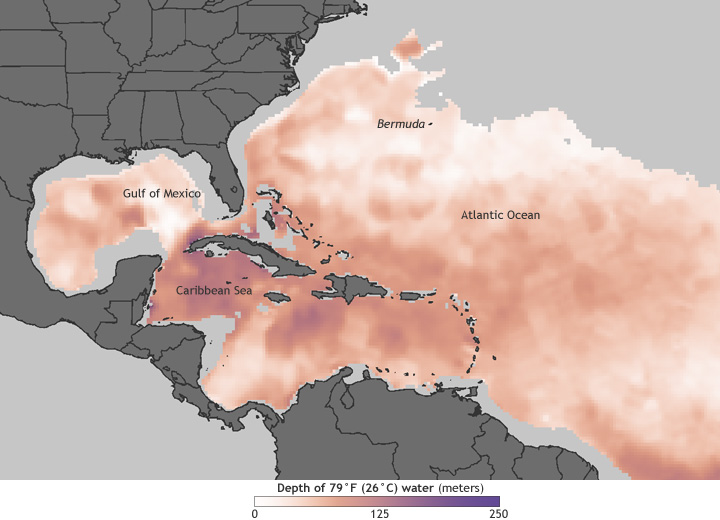

We are nearing the end of the most active part of the Atlantic hurricane season, but as of October 16, the layer of hurricane-friendly water was still plenty deep in the western Atlantic Ocean basin, especially in the Caribbean Sea. On average, water temperature needs to be at least 26 degrees Celsius (78–79 degrees Fahrenheit) to fuel hurricanes; the deeper the layer of warm water, the more favorable the conditions for a storm to strengthen. In late summer 2005, it was a deep reserve of very warm Gulf of Mexico water that allowed for the development of Hurricanes Katrina, Rita, and Wilma in quick succession.

The image above shows a new type of map that NOAA is producing every day to help researchers and forecasters study and predict where hurricanes are likely to form, strengthen, or weaken. Any place where the surface water is 26 degrees Celsius or warmer is colored pale pink; purple areas indicate very deep layers of warm water. On October 16, when this map was made, the layer of 26-degree-Celsius water in many parts of the western Atlantic was nearly 100 meters (330 feet) deep, and in the Caribbean the warm water layer was closer to 200 meters deep in a few places.

But while there was plenty of warm water available on October 16 to power any storms that happened to develop, the ocean is only half of the hurricane story. As of the October 16, 2 p.m. (EST) tropical weather discussion from NOAA’s National Hurricane Center, the atmospheric conditions across the Atlantic basin were not favorable for tropical storm development in the coming days. On the day of this map, the only Atlantic storm was Category 1 Hurricane Rafael, which was in the vicinity of Bermuda.

The new maps are part of a new suite of data products developed by researchers at the University of Miami based on data from NOAA’s World Ocean Atlas combined with satellite observations of sea surface height. (Height is a function of volume, and water’s volume gets bigger when its temperature rises). NOAA’s National Environmental Satellite, Data, and Information Service (NESDIS) made the new maps part of their routine (“operational”) data stream to provide hurricane forecasters with more timely and accurate estimates of ocean heat energy.