Lake Erie’s annual summer bloom of phytoplankton—algae and other microscopic, plant-like organisms—is underway and shaping up to be one of the most severe in the past decade. Not only can blooms be a nuisance, clogging water intakes and ruining the fun of boaters and beachgoers, they can also produce toxins that can poison wildlife, pets, and people.

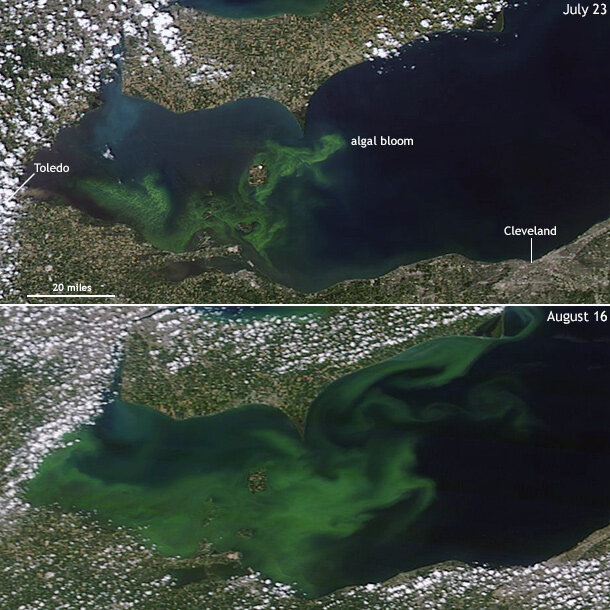

The eastward spread of the summer algal bloom in Lake Erie between July 23 and August 16. NASA satellite photos downloaded from Worldview.

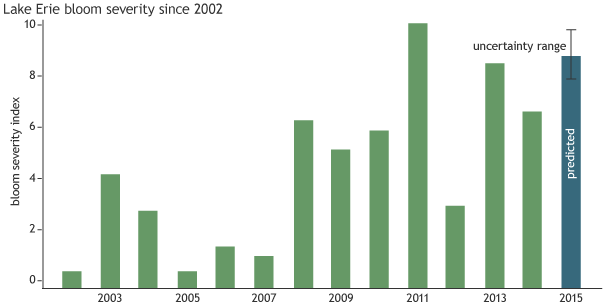

In early July, NOAA’s National Ocean Service and its partners issued a seasonal outlook that predicted the extent and duration of the 2015 bloom would be among the most severe of the past decade, with a bloom severity index score between 8.1-9.5, on a scale from 0-10.

Lake Erie bloom severity since 2002 (green bars) and predicted severity of the 2015 bloom (blue bar). The bar shows the mean severity predicted by 5 models, with the possible range shown with gray lines.

“Unfortunately, in early August, the bloom was already much worse than last year,” says NOAA’s Rick Stumpf, the lead ecological forecaster for the group at the National Ocean Service that studies Lake Erie’s harmful algal blooms. “This year’s bloom is following our earlier predictions for a severe event.”

The predictions come from a collection of ecological and climate models that capture the main influences on Lake Erie’s blooms, most importantly surface water runoff.

Runoff is important because as water flows across the farms and livestock feedlots upstream of the lake, it picks up excess fertilizer, which does the same thing in the lake that it does on land: stimulate plant growth. Temperature is also important because the blooms thrive best in warm, calm waters.

Avoid the scum

Warm, calm waters are especially favorable for the lake’s most common species of toxic cyanobacteria—bacteria that photosynthesize like plants. In response to one or more currently unknown environmental cues, the cyanobacteria turn on genes that allow them to churn out toxins that can be fatal to wildlife, pets, and people in certain doses.

In their experimental Lake Erie Harmful Algal Bloom bulletin on August 17, NOAA’s National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science and the Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory warned:

The Mycrocystis cyanobacteria bloom continue across a large part of the western basin south of West Sister Island from Michigan to the islands. Dense scums have formed in highest concentration areas… Keep your pets and yourself out of the water in areas where scum is forming.

Climate and blooms

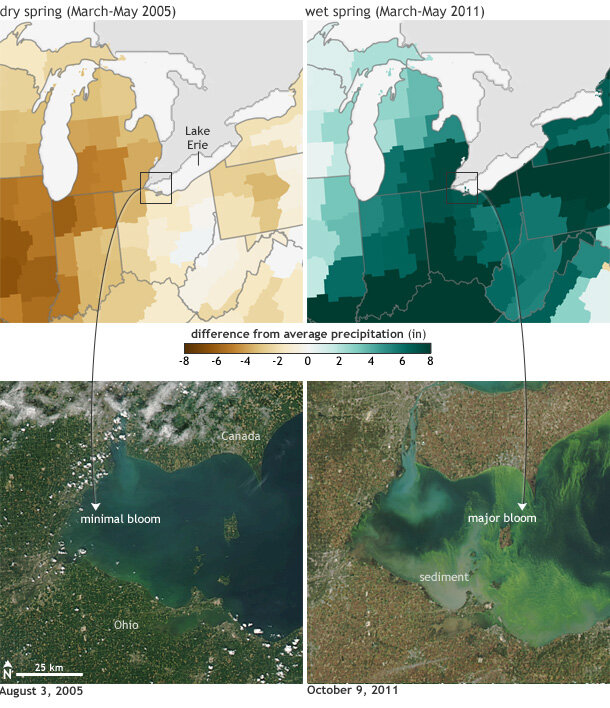

In Lake Erie, the bloom typically starts in late July, expands throughout August, and peaking in early September. The severity of the bloom is significantly influenced by spring and early summer rainfall. Wet springs lead to more fertilizer-laden runoff and more severe blooms. The bloom dissipates in late September and October as cold fronts start passing through, stirring and cooling the water.

(Top row) Difference from average precipitation for a dry spring (March-May 2005,) and a wet spring (March-May 2011). (Bottom row) NASA satellite image of the western end of Lake Erie in the respective summer/fall. The bloom was minimal in 2005 (left), but dramatic in 2011 (right). large versions: precip 2005 | precip 2011| satellite 2005 | satellite 2011

This year’s prediction of a large bloom hinged on record June rainfall. “April and May were dry, but June was very wet,” says Stumpf. “We don’t have any reason to update the forecast at this point,” he explains, “because no matter what happens in July and August [in terms of rainfall], the stage is set.” The June rains and runoff already delivered the nutrients needed to fuel a big bloom.

Predicting Toxicity

Whether that big bloom will be an especially toxic one is something that Stumpf and his colleagues can’t yet predict. In fact, when it comes to the Microcystis species that cause problems in Lake Erie, he says, “We don’t even really know what the purpose or function of the toxin is for the organism, why it makes the toxin some times and not others.”

But collaborating researchers have identified the genes that get switched on to make the toxin, which means that scientists can begin to explore whether there are certain cues from the environment—specific nutrient concentrations, temperatures, crowding, predation—that turn the toxin gene on.

“What I hope, of course,” Stumpf says, “is that we will find environmental triggers that we can add to the model…to be able to predict not just how big the bloom will be or how long it will last, but when and where we can expect it to become toxic.”