In our first post on the drought emergency in California and Nevada, we talked about conditions on a statewide level over the past two and half years. But a statewide average over a relatively long period can hide important variation from place to place, especially in a mountainous state like California, where the high elevations can get several times more average annual precipitation than adjacent valleys do.

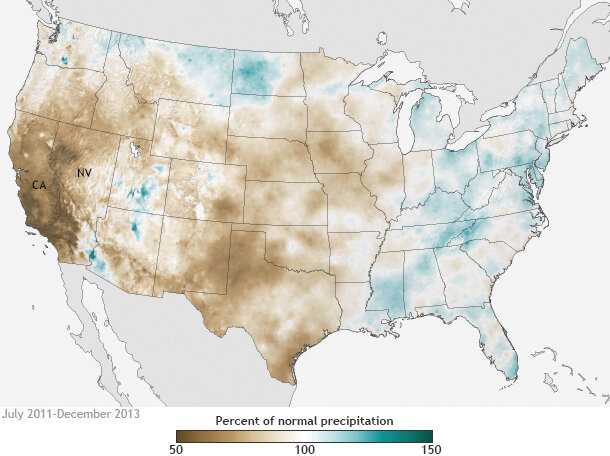

The map above shows the relative dryness from place to place, revealing that the 30-month precipitation deficits ending in December 2013 were more severe in southern California than northern California, and generally appear to be more severe in the mountains than in lower elevations. The accentuation of deficits over higher elevations is particularly meaningful, because it is in mountain catchments where much of California’s water resources are generated.

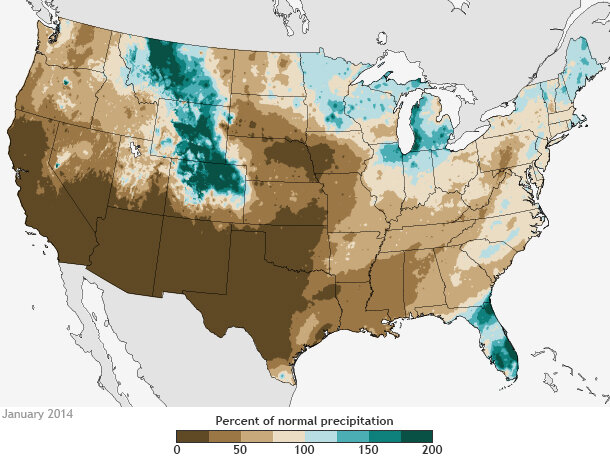

A little more than half the state’s precipitation typically arrives via winter storms in December through February. Observations collected during January indicate that no relief occurred; in fact the extreme lack of precipitation during October through December 2013 has intensified the deficit that had developed during the previous two water years. Throughout the area, ranchers with no pasture for their cattle are being forced to sell; wells are going dry, and wildfire responders are confronting small blazes in forests that are usually deep in snow this time of year.

Percent of normal precipitation in January 2014 compared to the 1981-2010 average, based on preliminary PRISM data. Most of California, southern Nevada, Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas received 25% or less of their normal precipitation.

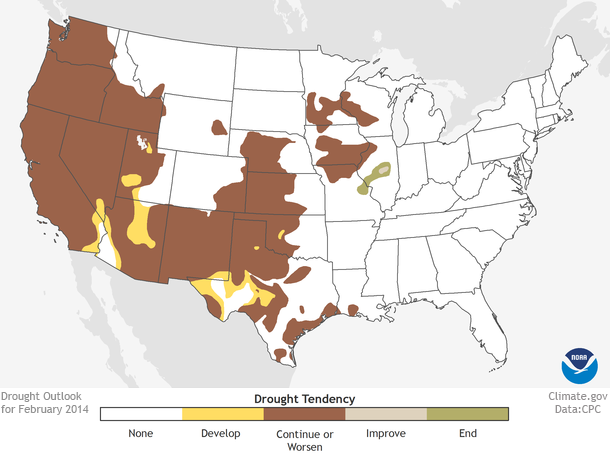

Unfortunately, NOAA climate scientists couldn’t give Californians any good news when they issued their monthly U.S. drought outlook on January 31, 2014. Drought is likely to continue or worsen through February across virtually all of California and the rest of the West Coast. Drought is likely to envelop the portion of the state that was not already in drought—a small sliver in the extreme southeast where California meets Nevada and Arizona.

Drought outlook for February 2014, based on data provided by NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center.