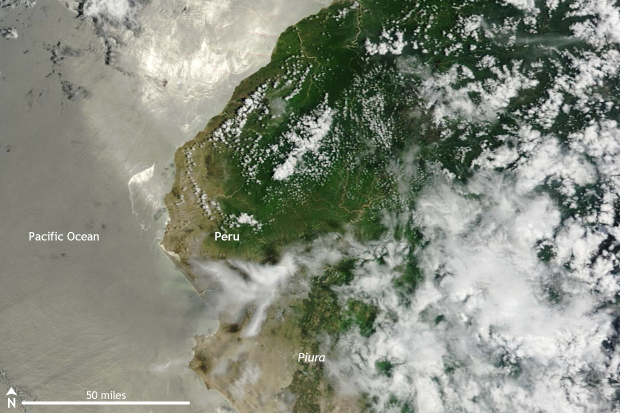

Since January 1, parts of Peru have experienced up to 10 times more rain than normal, leading to flooding and landslides in the usually semi-arid coastal landscape. The provinces of Piura and Lambayeque in northwestern Peru were hardest hit, although torrential rains have been observed off and on for the last two months across much of the country.

Grab and drag the slider to compare the before (left) and after (right) images of heavy rains and floods in Peru in February 2017. The pale tan of the normally semi-arid coastal landscape is transformed by the green-up of vegetation. NASA MODIS satellite images from Worldview.

The Southern Hemisphere summer—December through March—is also roughly the rainy season for most of Peru—rains extend into April. However, the amount of rain that has fallen since the start of 2017 has been enormous in comparison to average.

With more than a month left to the season, 2017 is already likely one of the wettest years on record for San Miguel in the Piura province. Around 10 inches of rain has fallen since January 1, when, on average, the entire rainy season usually totals just two inches of rain. Farther inland in the Piura region, a weather station in Morropón recorded 43 inches of rain since the start of 2017. At this point of the year—early March—Morropón’s average rainfall is about 4 inches. Rainfall totals in 2017 are 10 times higher than normal.

Farther south, the heaviest rains fell in the month of January. At Chuquibamba in the Arequipa province, around 8 inches of rain fell in January, more than double the average. Totals at the beginning of March are around 12 inches, 4 to 5 inches above the average seasonal rainfall total, with a month still to go.

The rains and resulting floods and landslides have killed at least 25 people and affected more than 200,000 people in Peru. In particular, inland rains which fell on the western slopes of the Andes Mountains have caused major issues. Heavy rain falling on steep terrain is a recipe for landslides. In Arequipa in southern Peru, landslides cut off the Peruvian Panamerican highway while floods killed at least three people in late January.

Monthly sea surface temperature anomalies in the eastern Pacific Ocean for February 2017 from NOAA's OISST dataset. Water temperatures off the coast of South America, especially Peru and Ecuador, were well-above normal, exceeding 9°F in some locations. This helped to enhance rainfall across Peru. NOAA Climate.gov image based on data from NOAA's Environmental Visualization Laboratory.

Why so much rain?

When it comes to global climate, Peru is famous for its role in discovering and understanding El Niño and the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO). Usually Peru observes torrential, flooding rains during El Niño when tropical Pacific ocean waters off the coast are above-average in temperature. Oddly, 2017 started off as a La Niña year, with ocean temperatures in the central/eastern Pacific below-average. No one told the coastal waters off Peru, though. Starting in mid-January, ocean temperatures began to warm considerably. Temperatures off the coast of South America were on average 3-7°F above-average in February with some locations 9°F warmer than average. In fact, the ocean was warmer in February in some locations than it was during the 2015-2016 El Niño! This led the Peruvian government to declare a "coastal" El Niño—not to be confused with the El Niño that we are more accustomed to in the central/eastern Pacific Ocean.

The warm ocean temperatures helped to increase the amount of moisture in the air that could be atmospherically churned into heavy rain over land. During a normal year, coastal sea surface temperatures are usually cool enough to act like a thunderstorm barrier for South America, keeping much of the rain far offshore. This year’s warm ocean temperatures did the opposite. In northern Peru, the warm ocean helped broaden the area where tropical thunderstorms occur, extending storms that would normally stay in the Pacific into Peru and Ecuador.

Meanwhile in southern Peru, where the climate and cause of summer rains are different, the warm ocean temperatures led to warmer than average air temperatures along the coast and provided enough moisture to allow rain showers, which normally fall across higher elevations along the Andes, to instead fall at drier and lower elevations with little vegetation. Heavy rains falling on dry soil in southern Peru is a recipe for mudslides and flash flooding. In some cases, these storms can even be blown all the way to the coast, raining over coastal towns and cities unaccustomed to heavy rain.

It has been a wet 2017 so far, and it is likely to get even wetter as the rainy season still has more than a month to go. All of which means that the threat of floods and landslides remains for many places in Peru.