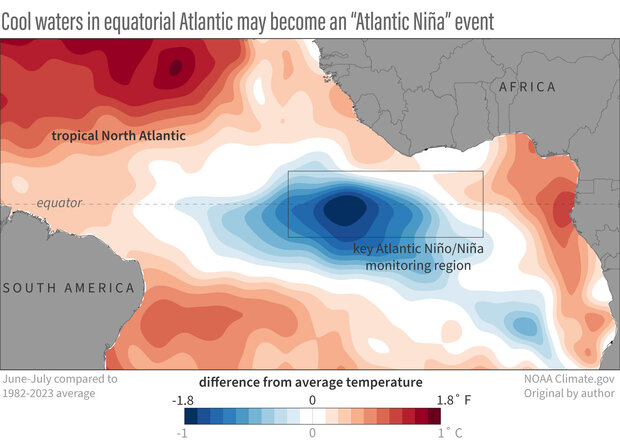

Earlier this month, we wrote about a pocket of cooler-than-average surface waters that had emerged near the equator in the eastern Atlantic in June and July. The localized cool spot was interesting because if it had continued at that strength through August, it would be classified as an Atlantic Niña—a natural pattern of warm-cool swings in the eastern equatorial Atlantic that affects seasonal climate in the region.

Average sea surface temperatures in June-July 2024 compared to the 1982-2023 average (with any long-term warming signal removed), showing the cool waters along the equator that might become an Atlantic Niña event. The black box outlines the specific area used for monitoring Atlantic Niños and Niñas. NOAA Climate.gov image, adapted from original by Franz Philip Tuchen.

Our plan was to wait give the August data a chance to come in and be analyzed before doing a follow-up post in early or mid-September covering whether the event formed or fizzled, what the potential influences could be on seasonal temperature and precipitation in the region, as well as some background on what we know and don’t know about why these events occur and whether human-caused climate change is expected to affect the pattern.

That post is still coming, but we are squeezing in a quick extra post because there has been a lot of interest in the event, as well as a bit of…let’s call it over-interpretation…in some corners of the internet (as well as the Climate.gov webmail inbox) that we want to tamp down if possible. In that pursuit, here are 4 things you should know about Atlantic Niñas and Niños.

#1: Atlantic Niñas and Niños don’t affect the whole Atlantic.

The June-July cold pocket hinting at a possible Atlantic Niña was located at the equator in the eastern Atlantic. The North Atlantic as a whole remains much warmer than normal. So does the tropical North Atlantic and the hurricane Main Development Region. There has been no Atlantic-wide cooling trend in the past couple of months. In fact, part of what makes the June-July cool conditions at the equator so interesting is how different that was to the rest of the Atlantic.

#2: The localized cooling that dominated the Atlantic Niña/Niño region in June-July appears to be weakening.

As we described in our first post, sea surface temperatures in the eastern equatorial Atlantic follow a counter-intuitive seasonal cycle. The region warms up through spring, but then cools in summer thanks to wind patterns that drive upwelling of deep, cool water. In June and July this typical cooling was stronger than usual. Since then, however, the cooling has weakened, as you can see in this animation of weekly sea surface temperatures compared to average.

Weekly maps of sea surface temperatures in the tropical Atlantic Ocean from May 1–August 22, 2024, compared to the 1981–2023 average. The relatively cool conditions in the eastern part of the equatorial Atlantic in June and July have weakened somewhat through August, making the possibility of an Atlantic Niña less likely. The maps have been de-trended, meaning the influence of global warming on the ocean temperatures in this area have been subtracted out. This technique gives us a better picture of how current conditions compare to the new, warmer normal of today. Without de-trending, the warm areas on these maps would look even warmer, and the cool areas would look less cool. NOAA Climate.gov animation, based on analysis of NOAA OISST data by Franz Philip Tuchen.

One criteria for Atlantic Niña is that the cool conditions must persist for at least 2 consecutive, 3-month “seasons.” In this case, that would mean May-June-July and June-July-August. Given the August weakening, it’s less likely this event will make the official cut. We will make a final call on that once we’ve had time to analyze August completely.

#3: Atlantic Niños and Niñas have regional impacts. Global impacts are less certain.

Atlantic Niños and Niñas are known to have a limited regional influence on rainfall variability in West Africa and South America. However, during the past several years multiple studies have also suggested that the impact of Atlantic Niño and Niña can reach far beyond the equatorial Atlantic, potentially influencing the development of hurricanes near the West African coast and possibly even El Niño and La Niña in the Pacific! But, not all scientists are on board with the new, global-impacts hypotheses. So, we need to let the science evolve to see if those hypotheses mature into “knowledge.”

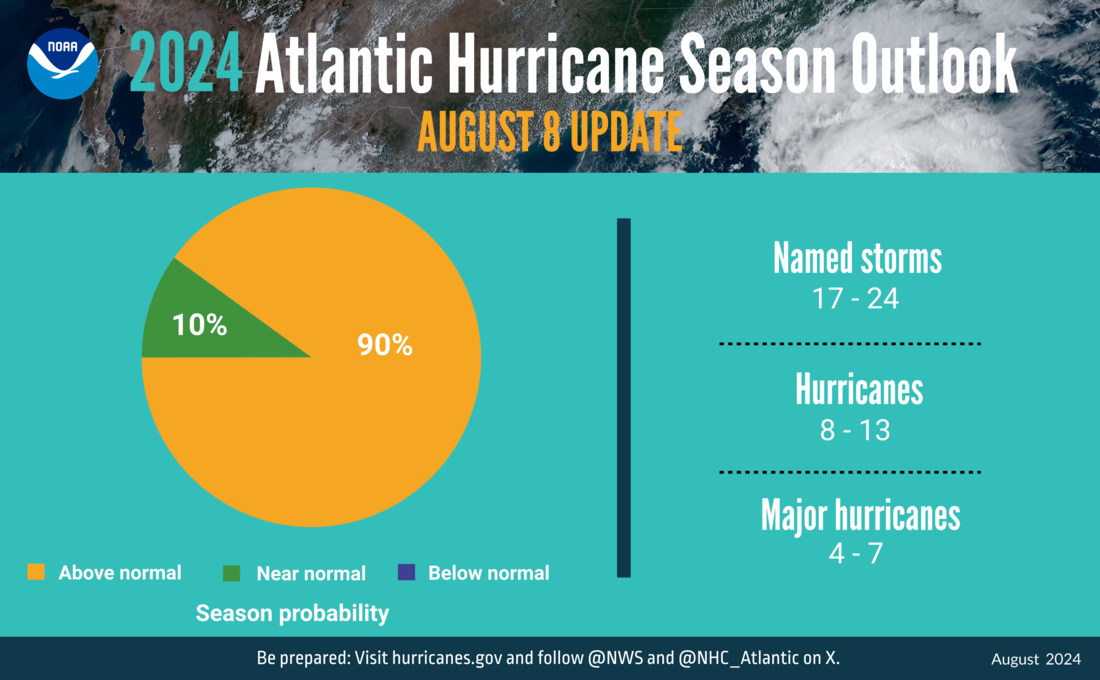

#4: The Atlantic hurricane season is still expected to be above average.

A summary infographic showing hurricane season probability and numbers of named storms predicted from NOAA's update to the 2024 Atlantic Hurricane Season Outlook. NOAA image.

A potential connection to the hurricane season was the least emphasized, most- caveated possible impact of a potential Atlantic Niña that we mentioned in our previous post. Those “ifs” and “mights” haven’t stopped some runaway speculation. To be clear, NOAA predicts the current Atlantic hurricane season will have above-average activity. Our guest author was not suggesting otherwise. He was simply offering a little real-time speculation about how a strong, persistent Atlantic Niña—if it were to form—might influence hurricane activity.

That musing is based on the fact that a 2023 study found that the presence of Atlantic Niños (the warm phase of the pattern) increases the number of Cape Verde hurricanes. Perhaps an Atlantic Niña would have the opposite influence. But even if an Atlantic Niña were to briefly dampen activity, there remain many other factors pushing the basin toward high levels of activity. And even within an active season, there can be periodic lulls in activity. That’s the difference between climate and weather.

We are heading into the heart of the Atlantic hurricane season, so it’s as important as ever for people to remain vigilant and pay attention to the watches and warnings from the National Hurricane Center and their local weather office.