We left off my previous post about the tremendous daily rainfall event on May 6 in Oklahoma City with a promise that I would explain what a one-in-a-100- or 500-year event actually means. Specifically, I was going to answer how we can even claim such things when records begin only around 100 years ago.

I was going to do this, except it has not stopped raining in Oklahoma and Texas, and the event itself deserves an update. A constant delivery of the necessary ingredients for heavy rains has meant record-breaking rains and flooding spread out over several weeks.

Total rainfall across the Southern Plains in May 2015. NOAA Climate.gov map, based on preliminary data from the PRISM climate group at Oregon State University.

While no single day in Oklahoma City has come close to the 7 inches of rain that fell in 24 hours, the city has still received repeated heavy rainfall for much of the month, including 3.73 inches on May 23. The city totaled 19.48 inches of rain during the month of May, smashing not only the previous May record of 14.52 inches (set in 2013), but also the all-time wettest month on record, which was 14.66 inches in June 1989. In short, the city has recorded almost 5 inches more rain than it ever has before in a single month. The city receives only 4.65 inches in May on average.

This hasn’t been just a wet period for Oklahoma City; the entire state has recorded a great deal of precipitation. May rainfall has been at least 200% greater than normal statewide, with southern Oklahoma seeing rains 400% above average (over 20 inches of rain). For reference, the 30-day accumulated total (May 2-31) of over 23 inches of rain near Oklahoma City according to one weather station would be a greater than a 1-in-1000 year event. This means that every year there is only a 0.1% that any 30-day period would record that much rain.

May 2015 rainfall compared to normal (1981-2010). NOAA Climate.gov map based on preliminary data from the PRISM climate group at Oregon State University.

The wet weather was not simply an Oklahoma affair. Texas has also received its fair share of drenching rains during the month of May, and in particular over the last two weeks. From Houston to Austin to Dallas, torrential one- to two-day rainfall of 4-12 inches has created havoc. In fact, the suburbs of Houston received up to 11 inches of rain in just 24 hours on May 26. According to the state climatologist of Texas, the state has averaged 7.54 inches of rain in May, which is almost an inch higher than the previous record wet month (June 2004).

Austin has received 17.59 inches of rain already, beating the previous May record by 3.49 inches, while Dallas/Fort Worth has also set its wettest May record by over 3 inches. Overall, in the month of May, one to two feet of rain has fallen across Texas and Oklahoma, greater than 200% of normal. Rivers rose rapidly in response to the sudden influx of water. And just like in Oklahoma City on May 6, the National Weather Service declared flash flood emergencies for the hardest hit areas.

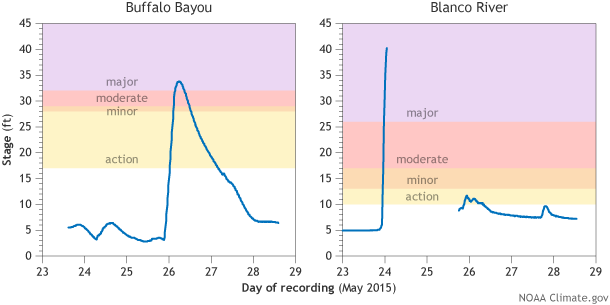

Along the Blanco River in Wimberley, Texas, roughly halfway between Austin and San Antonio, downpours of rain upstream led to river levels rising 35 feet in only 3 hours on May 23-24, cresting at least at 40.21 feet, after which the gauge stopped recording. This was 14 feet above the major flood stage and an amazing 7 feet higher than the previous record level. Rivers burst their banks all across the state with flooding in major metropolitan areas, including Austin, Houston, San Antonio, and Dallas. At least 28 people have lost their lives, with others still missing.

River levels on the Buffalo Bayou (left) in Houston and the Blanco River (right) in Wimberley, Texas, in late May 2015. The Blanco registered 40.21 feet—7 feet higher than the previous record—before the gauge went offline.

Combined together, these individual weather events have made for a climate-scaled catastrophe and a serious case of weather whiplash. This region of the United States was suffering from drought conditions for the better part of the last 4 years. All drought is expected to disappear due to the recent rains.

The culprit for these events has been a parade of slow moving storms and a very moist air mass courtesy of the Gulf of Mexico.

Average wind speed (color) and direction (arrows) at the 300-millibar atmospheric pressure level for May 5-26, 2015. The jet stream persistently steered storms full of moisture into the Southern Plains states of Texas and Oklahoma. NOAA Climate.gov map by Hunter Allen, based on NCEP/NCAR Reanalysis data provided by NOAA ESRL.

On a seasonal climate timescale, above-average rains during the spring across the southern tier of the U.S., including Texas and Oklahoma, is a pattern often seen during El Niño events. During El Niños, the jet stream (an area of fast moving winds high in the atmosphere) can extend across the southern US, helping to track storms across the south, including the type of storm systems capable of producing the severe thunderstorms that soaked the region (compare the above figure to the wintertime El Niño pattern). During May, this was exactly what happened, leaving Texas and Oklahoma in a prime location for stormy weather.

Of course, El Niño alone cannot account for the record-breaking nature of the rains. We cannot discount the influence of natural variability of our atmosphere (extreme weather sometimes just happens), as well as some influence from climate change, since extreme precipitation events are likely to increase and have increased as the planet warms and the atmosphere gets wetter.

No matter how we look at it, recent events in Oklahoma and Texas have been rare. From 7-11 inches of rain in one day, to monthly rainfall amounts never seen before, there has not been a shortage of 1-in-25, -50, -100, even -1000 year events. Stay tuned for an upcoming post that gets into the nitty-gritty of how this is done—even when we only have 100 years’ worth of observations. To get you thinking in the right direction, remember that just because you don’t have all the letters in a Wheel of Fortune puzzle doesn’t mean you can’t figure out the answer