About the last thing you would expect to hear from an island surrounded by the vast Pacific Ocean is that there is a shortage of water. Yet an El Niño-dominated atmosphere has led to widespread drought across Pacific Island Nations, causing states of emergency to be declared for Palau, the Marshall Islands, and the Federated States of Micronesia.

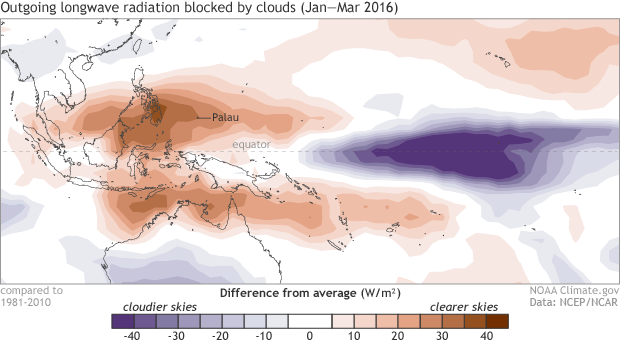

Outgoing longwave radiation anomaly averaged from January through March, 2016. Positive values (brown colors) reflect clearer skies than normal allowing for more outgoing longwave radiation to leave the planet. Negative values (blue colors) reflect cloudier skies blocking more outgoing longwave radiation than normal. Clearer skies than normal occurred over much of the western Pacific Ocean while cloudier skies were observed over the central/eastern Pacific Ocean, consistent with an ongoing El Niño. The lack of rain over the western Pacific Ocean has led to drought conditions on many Pacific islands. NOAA Cliamte.gov map based on data from NCEP/NCAR Reanalysis.

A shifted Walker Circulation along the equator due to El Niño caused rainfall to fall much farther east than normal during the last several months. Koror, the capital of Palau, has seen a third of its normal rainfall since March 1 and the lowest recorded rainfall in 65 years since the start of 2016. It is in the midst of an “extreme drought.” Since January, only about 8 inches of rain have fallen, nearly 22 inches below average. According to news reports, Palau President Tommy Remengesau has declared a state of emergency as the Ngerimel Dam, which supplies water to Koror, has dried up. The levels in the only other source of drinking water, the Ngerikiil River, are very low. The city is simply running out of water and water rationing has begun.

The Federated States of Micronesia—including the islands of Yap, Chuuk, and Pohnpei—are facing similar extreme drought conditions as rainfall has been well below average over the last several months. Damaged crops and an increase in grass fires are expected. In the Marshall Islands, the drought has caused the president to declare a state of disaster with the entire Marshall Island chain in “severe” or “extreme drought.” Greatly reduced water supplies and extensive damage to food crops is likely.

Islands in the Pacific Ocean may be surrounded by water, but they rely on fresh rainwater for drinking and watering crops. Severe droughts associated with El Niño can negatively impact food security, public health, and the economy. During and after the historic 1997-1998 El Niño event, “severe drought” similarly impacted islands across the western Pacific.

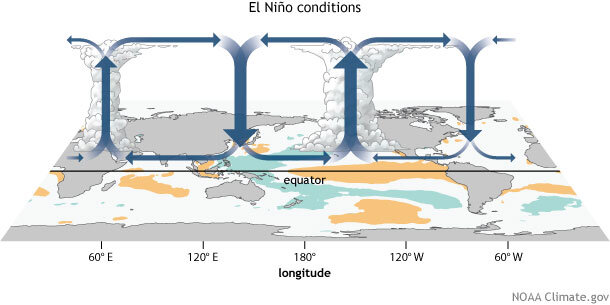

Generalized Walker Circulation (December-February) anomaly during El Niño events, overlaid on map of average sea surface temperature anomalies. Anomalous ocean warming in the central and eastern Pacific (orange) help to shift a rising branch of the Walker Circulation to east of 180°, while sinking branches shift to over the Maritime continent and northern South America. NOAA Climate.gov drawing by Fiona Martin.

I know I can’t blame everything on El Niño, but what about this time?

Yes, you certainly can. As mentioned previously, El Niño shifts around the Walker Circulation—an equator-wide atmospheric circulation that normally means rising air and rainfall across the western Pacific and sinking air/dry conditions over the central and eastern Pacific. During El Niño, the rising air and subsequent rainfall follows the anomalously warm waters to the central and eastern Pacific like a kid running after an ice cream truck. This leaves normally wet areas, like the islands across the western Pacific, much drier than normal. This was exactly the case this year.