March 2016 El Niño update: Spring Forward

The strong El Niño of 2015/16 is on the decline, and the CPC/IRI forecast says it’s likely that conditions will transition to neutral by early summer, with about a 50% chance of La Niña by the fall. In this post, we’ll take a look back at this past winter and forward to what may happen next.

Current events

El Niño has begun to weaken, with sea surface temperature anomalies across most of the equatorial Pacific decreasing over the past month. The large amount of warmer-than-average waters below the surface of the tropical Pacific (the “heat content”) also decreased sharply, despite getting a small boost in January. The heat content is the lowest it’s been in over a year, and since the subsurface heat feeds El Niño’s warm surface waters, this is another sign that the event is tapering off.

That said, there’s still a lot of extra heat in the tropical Pacific, and we expect El Niño’s impacts to continue around the world through the next few months. So far this winter, global rain and snow patterns have mostly been consistent with the expected patterns of El Niño, with some exceptions.

The winter that was

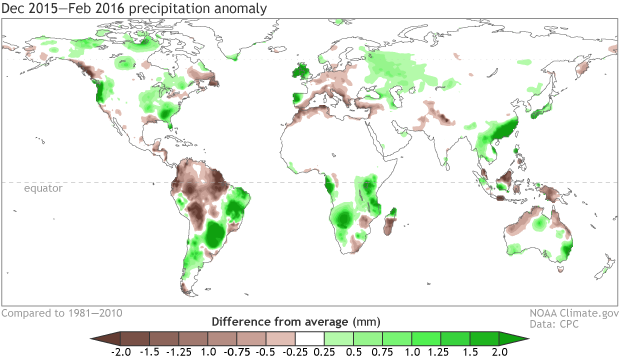

December 2015 – February 2016 rain and snow patterns, shown as the difference from the long-term mean. Climate.gov figure from CPC data.

In South America, southern Uruguay, Paraguay, and southern Brazil have received much more rain than their long-term December–February average, and the northern portion of the continent has been dry, as usually occurs this time of year during El Niño. Also consistent (so far) with El Niño’s typical impacts have been Africa’s rainfall patterns (wet in portions of Kenya and Tanzania and dry in southeastern Africa and southern Madagascar), the dryness through Indonesia and northern Australia, and the rains in southeastern China.

As Michelle discussed, the precipitation impacts in North America haven’t been quite as consistent with expectations so far, although the southeast and particularly Florida have received a lot more rain than average. Over the December–February season, the western coast of North America showed a pattern of drier north/wetter south, but the line between the two is shifted somewhat north of where it was during earlier El Niño events.

It’s a warm, warm world

El Niño’s effect on regional temperature is a little less distinct than its effect on precipitation patterns. Since El Niño changes the circulation of the atmosphere all around the world, it essentially changes where we expect rain to fall by steering storms to different locations. Temperature operates differently, especially since global warming is changing the averages. Michelle broke down some of the factors going into the super warm November and December in eastern North America – a good example of how attribution of seasonal temperature patterns is a complicated matter.

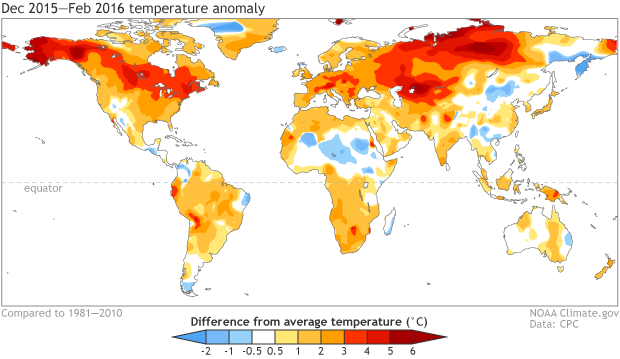

December 2015 – February 2016 surface temperature patterns, shown as the difference from the long-term mean. Climate.gov figure from CPC data.

Looking forward

Where does the 50% chance of La Niña come from? Forecasters take into consideration what happened in the past, the predictions of computer models, and current conditions when making their forecast.

La Niña conditions have followed six of the ten moderate and strong El Niños since 1950, including two of the three previous strongest El Niños. However, this small number of cases means that it’s hard to make a very confident forecast based only on the previous events.

Next fall is still many months away, and computer climate models have a difficult time making accurate forecasts through the “spring barrier” period of March–May, which is the time of year when El Niño and La Niña are often weakening and changing into neutral. It’s harder to predict a change in conditions. Nevertheless, most computer models are in agreement that La Niña (strength TBD) will develop by the fall.

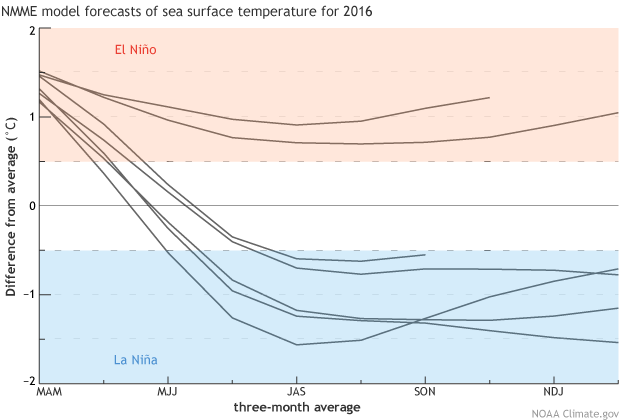

Forecasts from seven climate models for the 3-month-mean average sea surface temperature anomalies in the Niño3.4 region (Oceanic Niño Index). The first 3-month-mean period shown is March—May 2016, “MAM”; the last is December 2016—February 2017. Model data from the North American Multi-Model Ensemble (NMME). Climate.gov figure.

There are two models in this graph that are showing a return of El Niño. When a computer model forecast is made, you first have to tell the model what the current conditions are (“initializing” the model). For example, you tell it the current sea surface temperature, so it knows where to start.

The way we get a variety of possible outcomes is to start the models with slightly different initial conditions; the differences grow over time. Modelers can use different observation data sets, or use a few different recent days from a single data set, or use one set of observations and add in the range of uncertainty. (For more on observations, check out Tom’s excellent post.)

The two models that show a return to El Niño happen to use the exact same data set for the initial conditions. The prediction models are different, so they react to the initial data differently, which leads to different outcomes. However, this particular data set used for the initial conditions has unrealistically cold temperatures in the tropical Atlantic Ocean. This smells fishy so it is currently being investigated. The fact these two models are both predicting El Niño next winter could be related to this issue.

To ENSO researchers, this is pretty interesting, because the relationship between the Atlantic and the Pacific isn’t very clear. But right now, it means we aren’t placing a lot of weight on those forecasts for El Niño next year. The next few months should give us a clearer picture.

Comments

Add new comment