Reflections on a really big drought

In the monitoring branch, our temperature analyses garner a lot of attention. We are asked big questions such as: What was the warmest year on record? How fast are global temperatures changing? These are important questions that we work to answer, but our regional-scale data and services also have immense benefits.

Someone smarter than me once said, “No one ever died under a global temperature time series.” This is a great way to say that we can report on global average temperatures all we want, but it is the local impacts of change and variability that matter for the average person. At the National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI), we work tirelessly to translate our treasure trove of data into something meaningful, and our work during the Southern Plains drought highlights these efforts.

Brazos River runs dry in Knox County, Texas, in summer 2011. By Earl Nottingham, © Texas Parks & Wildlife Department.

The Southern Plains drought lasted more than four years before coming to an end very quickly in the spring of 2015. There is an old adage that big droughts end in big floods, and that was the case in Oklahoma and Texas, when a slow-moving climate disaster was washed away by a fast-moving catastrophe.

Flash flooding stalls traffic on I-45 in Houston on May 26, 2015. Photo by Bill Shirley, available through a CC license.

The drought was the defining event of the first four years of my career monitoring the U.S. climate system, and now that the event is over, I hope the data, services, and information that NCEI provided helped with the understanding of the event and allowed decision makers to go beyond the data and lessen the impacts for those affected.

My work monitoring the U.S. climate at the NCEI began in the summer of 2011, during the early stages of the Southern Plains drought. My task was to analyze temperature and precipitation data and determine what the public needed to know. Communicating the urgency of this drought also had to be balanced with highlighting other important events such as the warmest year on record for the contiguous U.S. in 2012 and the on-going drought in California. This was a true trial by fire. Monitoring any climate disaster as it unfolds, trying to give meaning to the data, is a humbling experience.

During the Southern Plains drought, we connected our data to the wildfires that charred millions of acres, record-low water levels in vital reservoirs, damaged crops, and decimated herds of cattle. Our data helped to quantify the impacts on the ground, helping decision makers to make the most informed decisions on issues from water resource management to disaster declarations.

Flames burn out of control at Possum Kingdom Lake near Pickwick, TX, on April 15, 2011. Photo by Texas Military Forces, available through a CC license.

The beginnings of drought

Drought conditions began affecting the Southern Plains during the winter of 2010-11 and spring of 2011. That winter was marked by a moderate-strength La Niña event, which means there was an area of below-average sea surface temperatures in the equatorial Pacific. During wintertime La Niña events, the preferred storm track across the U.S. tends to be more northerly, suppressing precipitation across southern regions. This jet stream pattern set the stage for the drought with below-average precipitation observed across Oklahoma and Texas.

Drought descended on the Southern Plains between October 2010 and September 2011. Parts of the region received just 20% of their twentieth-century average precipitation (dark brown). (To avoid splitting winter rains across two calendar years, scientists often track annual precipitation in the West by "water year.") NOAA Climate.gov map, based on Climate Division data provided by NCEI.

Drought conditions exploded during the summer of 2011. The season was record warm for much of the Southern Plains. The Oklahoma and Texas summer temperature of 86.8°F was the warmest statewide average temperatures in our entire 1895-present dataset. It was also the third driest summer for Oklahoma and the record driest for Texas, marking back to back record-dry seasons for the state.

By the end of the summer, 99.9 percent of Texas was in drought with 81.1 percent of the state mired in the worst category (D4, Exceptional). All of Oklahoma was in drought, including 69.2 percent of the state in exceptional drought. Statistically speaking, “exceptional” drought is expected to impact an area once every 50 years.

Drought conditions across the United States as of August 30, 2011. Virtually all of Texas and Oklahoma were experiencing "exceptional" drought. NOAA Climate.gov map from Data Snapshots, based on data from the National Drought Mitigation Center.

In terms of the temperature and precipitation data, the drought intensity peaked in the late summer and autumn of 2011, and was the most intense drought on record for Texas. The spring, summer, and autumn of 2011 were so warm and so dry that it took until the spring of 2015—nearly four years—for the region to even come close to recovering. Over the course of the four years, small-scale precipitation events brought some short-term drought relief, but longer-term precipitation deficits added up, as did the impacts. From 2011 to 2014, the drought in the Southern Plains resulted in over 15 billion dollars in damages.

A wall of smoke towers in the background of this September 5, 2011, photo of a stretch of Highway 71 in Bastrop County, Texas. Photo by Michael Rose, through a CC license.

The Drought Ends

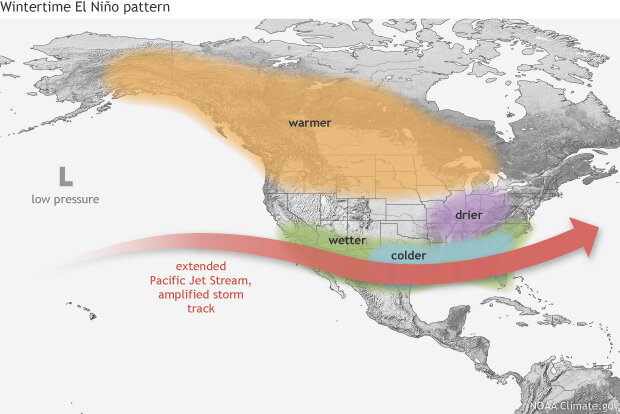

The spring of 2015, particularly May, brought record amounts of precipitation to the region. The development of a moderate El Niño event, which is the opposite of a La Niña, favored above-average precipitation in the southern United States. (See more from our colleagues’ ENSO blog.) Enough precipitation fell to mostly make up for the long-term precipitation deficits across the Southern Plains and refill reservoirs to above-average levels.

Typical impacts of El Niño on the jet stream and winter climate across the United States. NOAA Climate.gov map by Fiona Martin.

Texas and Oklahoma both had their wettest months on record in May 2015 with more than twice the average precipitation. Enough precipitation fell across the central U.S. that when we averaged precipitation across the entire contiguous U.S., it was the wettest month the Lower 48 had experienced since records began in 1895. Although the rains were beneficial in terms of drought recovery, they also caused record flooding. Lives were lost and property was damaged as the rain fell too quickly for natural and built systems to manage.

Each state's May 2015 precipitation ranked according to the 121-year historical record, from 1895-2015. No place was record dry, but Texas, Oklahoma, and Colorado each experienced its wettest May on record. NOAA Climate.gov map, adapted from originals provided by NCEI.

The drought as well as the flooding will likely be remembered in Texas and Oklahoma for generations, much like the Dust Bowl of the 1930s and the drought of the 1950s. When reflecting on this drought, I can’t help but think about the countless people who observed, recorded, and analyzed those previous events. Their work made it possible to put this drought into a proper historical context. It is also a reminder of why the work we do at NCEI is so important. I like to think that the data we safe keep today and our analysis of that data will help future generations be better equipped to face the challenges of tomorrow.