Prairie fires on the Southern Plains

Welcome to Beyond the Data. This week, we’ll talk a little bit about wildfire. Specifically, prairie fire.

Before we do that, I hope you don’t mind if I take a second to process a couple of facts about March 2016. First, that the world’s land areas averaged 4.2°F warmer than the month’s 20th century average. Second, compared to March’s 1981-2010 “normal,” the Northern Hemisphere’s combined area of “missing” sea ice and snow cover would cover more than a tenth of the moon.

(stunned silence) Whoa.

Now let’s talk about the prairie

In our previous entry, we visited a little bit about 2016’s very warm start across the United States, and the regional pockets of very dry conditions among that warmth. Here’s the short version: very warm temperatures can make dry spells even drier by pulling more water out of the soil through evaporation and plant transpiration, a process known as “evapo-transpiration”.

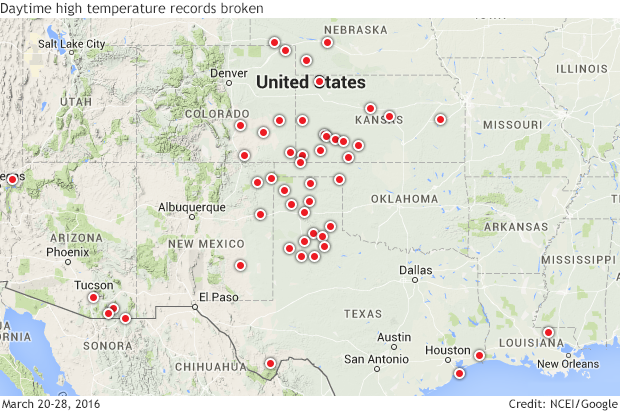

The Southern Plains was one of those dry areas made worse by very warm temperatures. What was already a warm start to 2016 spiked during the third week of March, when record and near-record temperatures blanketed the area. This map, grabbed from NCEI’s “Daily Records” tool, shows the number of records made during the week.

Map from the NCEI Daily Weather Records Tool showing places where daily maximum high temperature records were broken between March 20 and 28.

The result was pretty much what you’d expect after a dry, warm winter on the prairie—the dormant grasses were ready to burn. Wildfire season in the region generally peaks in March, and drought stress makes things worse. By late March, some huge wildfires erupted in Kansas and Oklahoma.

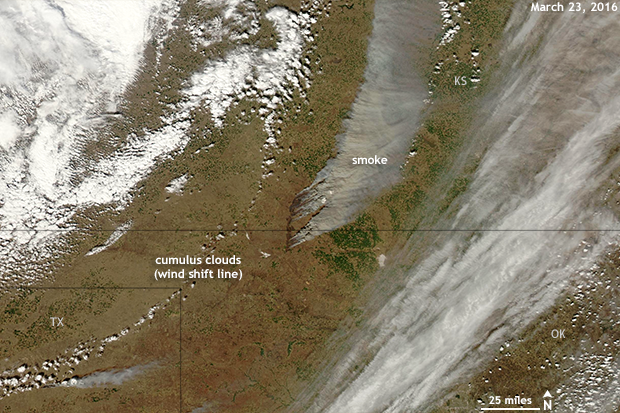

The image below, from our friends at NASA, shows a very large fire, still burning on March 23 after starting a few days earlier in Oklahoma. The fire was driven by strong southerly winds, as evidenced by its south-to-north burn scar.

A prairie fire driven by strong southernly winds burns on the Southern Plains on March 23, 2016. NOAA Climate.gov image based on NASA Worldview Aqua/MODIS.

How does climate play into this? The data show that winter was warm and dry, but going Beyond the Data, another factor made this large fire a catastrophically large fire.

The Southern Plains region is well known for its violent spring weather. Several ingredients need to come together to produce violent weather; one of those ingredients is a trigger, or some kind of focusing mechanism to get storms started. In the spring, that function is often served by the “dry line”, a boundary between moist Gulf air and the dry air of the West. The dry line is possible year-round, but it’s an almost ever-present feature somewhere in the Southern Plains from March through May.

You can actually see a wind shift line in the image above. It’s marked by a dotted thin line of puffy, white cumulus clouds arcing from west of the fire down to the southwest corner of the image. In this example, that wind shift line is more of a cold front, but the concept is the same. If the other ingredients for severe weather were present that day, those little puffy clouds could have grown into large thunderstorms. But they didn’t.

Right angle, wrong turn

And that’s how we get back to climate. When the climate situation intensifies fire danger conditions deeper into spring, the fire season mingles even more with dry line season. On the day pictured above, on the east side of a dry line, winds were strong from the south. After the dry line passed, winds howled out of the southwest. It was the first of two wind shifts that day. The cold front seen above, brought more westerly winds a short time later.

That 90-degree-angle wind shift is a nightmare scenario for the professionals and volunteers that fight prairie fire. Once the dry line passed the fire line, the winds shifted from southerly to more westerly, and the entire fire line made an abrupt right turn. What was previously the right flank of the fire became the “head of the fire.” What was once a long skinny needle poking into Kansas became a wall of fire, dozens of miles wide, raging across two states.

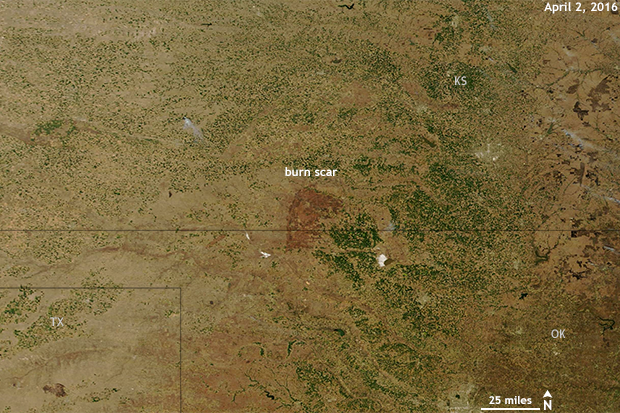

The result that day—and for several days afterward—was pretty terrifying. An image taken a couple days later shows just how devastating, and complete, that right turn was.

A burn mark miles long scars the plains on April 2, 2016, evidence of a prairie fire that burned for days. NOAA Climate.gov image based on NASA Worldview Terra/MODIS.

Coda

I think the most consistent feature of my Beyond the Data blogs is me mentioning I’m from Oklahoma. I apologize if it gets repetitive, but I miss it sometimes. For starters, my mom lives there, and she’s amazing.

One of my old jobs in Oklahoma was with a wonderful program that worked with the public safety community to prepare for hazardous weather, or the effect that weather would have on hazardous situations.

At the time, I thought I was teaching people about the weather, but what happened was the weather taught me about people. And here’s what I learned about fire pros and volunteers: they’re amazing. Almost as amazing as my mom, and that’s up there. If you know a smokejumper or brushpumper, you know what I’m talking about.