From giant hailstones to the most snow in a day, state extremes show us just how BIG the weather can get

In the last few weeks, my colleague Karin Gleason and her colleagues around the country finalized a number of state climate extremes records and reports. Some of these were recent record-breaking events; some were recently discovered as data continue to be liberated from paper into the digital world; and some were backlogged because somebody had let them linger too long (here’s where I blush and stare at my shoes).

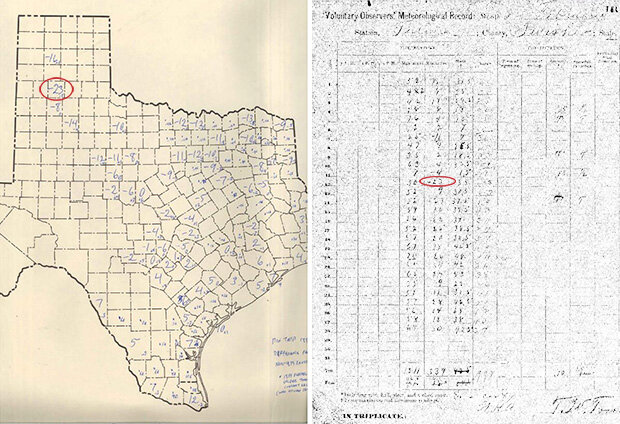

(left) Map from the Office of the Texas State Climatologist with hand annotation of record low temperatures for February 1899 by county. (right) Digital scan of Tulia, TX observer form for February 1899. Images taken from the official state extreme report.

Here’s what Karin and Friends determined in the last month or so:

- The 4.75” diameter hailstone that fell in Minooka, Illinois, in June 2015 was indeed the largest retrieved and reported in the Illinois record.

- The 199 mph wind gust observed on Ward Peak in February 2017 was indeed the strongest known wind gust in California’s observing history.

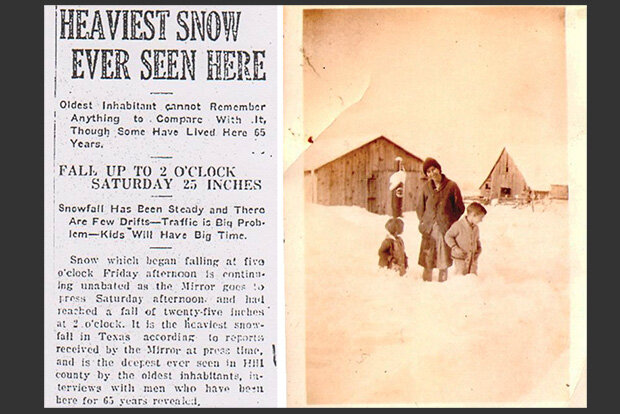

- The 26 inches of snow that fell on December 20-21, 1929, in Hillsboro was the largest 24-hour snowfall of the Texas record, breaking a record set in 2009 (wait, what?)

- The -23°F temperature observed on a February 1899 morning in Tulia, Texas, was the coldest on record for the Lone Star State, tying the record set 44 years later (wait, what?) in Seminole.

- The 90.65 inches of rain that fell in West Milford Township during 2011 was the most a New Jersey station has recorded in a calendar year.

If you’re thinking “Hasn't it been 119 years since 1899?” and "How can an event that old set a new record?" you’re not alone. We’ll come back to that.

A tree snapped during the February 2017 high-wind event that generated California's strongest known wind gust. Photo courtesy of Will Paden, as included in the State Climate Extremes Committee report related to the event.

Where did these values come from?

About 15 years ago, my colleague Karsten Shein took on the task of assembling a list 250 potential records—an initial set of five per state—and sent it out for examination and review by the State Climatologists of these United States. The surviving observations from that process are the base of the current list of state weather and climate records.

Today, any changes are adjudicated by a jury of experts from five institutions: the State Climate Office, the Regional Climate Center, the National Weather Service Forecast Office, the NWS Regional Headquarters, and the National Centers for Environmental Information. Each review, and the recommendation of the committee, is captured in a report detailing the observational challenges and review methods.

I should point out here that these are the state records recognized by NOAA and our amazing partners in the American Association of State Climatologists. There are other, perfectly fine, lists of weather and climate records out there. Ours can differ in some details; we’ll cover that below.

So, why are these important?

I mean, who doesn’t get the itch to know when and where the largest hailstone fell in Kansas? (by the way, Coffeyville, 1970, if you’re going by weight or circumference; Wichita, 2010, if you’re going by diameter).

But these records have value beyond their (admittedly, seductive) trivial allure. They are valuable because they [imperfectly] address the question: how big can the weather get around here? They tell us about where we live, and what is possible, in the places we live.

A clipping from the Hillsboro Mirror about the record-setting snowfall in Hillsboro, TX, in December 1929 was one of the pieces of evidence that the extremes committee used to corroborate the new-old record. Image taken from the NWS Dallas/Fort Worth weather office website. Originally provided by the McIlroy family.

The NOAA state records have a few constraints that may make them less extreme than other lists. For example, the record warm temperature for the great state of Hawaii is 100°F, at a place called Pahala. Now, yes, anybody silly enough to bring a thermometer close enough to a Hawaiian lava flow will record an air temperature warmer than 100°F, even if it’s the last thing they record. Nobody is going to live near flowing lava, for too long, anyway. So some of the weather variables (temperature, precipitation) need to be observed by a fixed station, which, more or less, live where we live. Moreover, when possible, the data have to end up in some kind of archive, so that our grandkids can retrieve it. This is kind of important.

What could possibly go wrong?

Our list isn’t perfect. It’s hard to measure extremes. They are literally at the boundary of what we know to be possible. So these lists operate in a space where plausibility reigns over certainty.

Our list doesn’t recognize all observing platforms. There are radar-estimated winds that exceed state records. Where do they go? For now, they don’t go in our list, which requires direct observation.

The list represents what is systematically observed, which is a much smaller sample than "everything that has happened." We don’t pretend that the 4.75” hailstone that was retrieved in Minooka was the largest that has ever fallen in Illinois; surely other, larger stones have fallen. But this was the largest that a person picked up, preserved, measured, and ultimately shared with the NWS.

(aside: if you suspect you’re holding a record hailstone and want to properly process and report it, there’s guidance for that)

This hailstone retrieved in June 2015, with a diameter of 4.75 inches, is the state record for Illinois. Photo from the State Climate Extremes Committee report that documented its occurrence and retrieval.

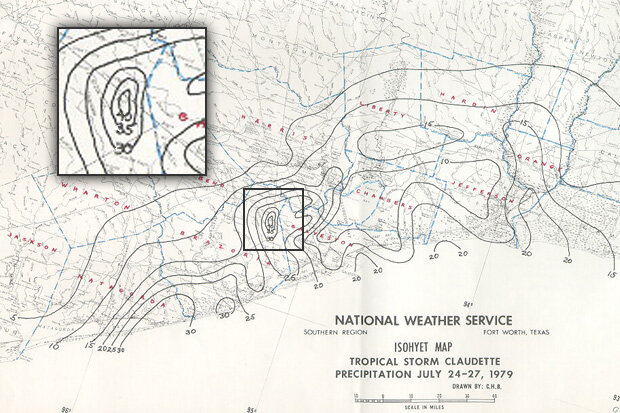

Sometimes, weather just overwhelms the observing equipment. The Texas state record for rainfall, set during a tropical storm in 1979 is an exception to our “purpose built equipment” constraint. Rain gauges aren’t built to measure 40+ inches in a day. So the total was assembled kinda forensically by a previous team looking into the event. They used rain gauge information from observers who were able to dump their gauges as they filled up—typically every ten inches. That study also used some opportunistic examination of vessels not made for accurately measuring rain—this is called a “bucket survey” in the business. The results of the fairly exhaustive study were adopted by the committee.

A contour map of 24-hour rainfall accumulation along the Texas Gulf Coast during Tropical Storm Claudette in July 1979. The station at Alvin (inset) holds the record for the most rain recorded in a 24-hour period anywhere in the United States.

Finally, as data continue to be rescued from paper and thrown into the digital world, records can be set retroactively (see the two Texas records above). As observing networks are commissioned into our official archives, records can be set retroactively (see the New Jersey record above).

What goes right?

One of the really unexpected benefits of doing this work, together, is that it helps inform observing practices—how and where and when and how well we measure what we measure, and the kinds of things that can lead to invalid data. We learn more about the subtleties of meteorology that can lead to huge events—the local experts from the Weather Service and State Climatologist offices provide rich detail in that regard.

And, going Beyond the Data, we also learn about just how extreme our weather can get.

Comments

Add new comment