Bad news for Southeast peaches: Something freezing this way came

In mid-March, a cold air outbreak brought freezing temperatures to the Southeast devastating crops and causing over $1 billion in agricultural losses. For those of us who love fruit this is bad news and potentially means higher prices at the supermarket and farmers’ market. In this Beyond the Data post, we will explore some of the impacts of the freeze and why it was so devastating even though freezing temperatures in mid-March aren’t that unusual for the Southeast.

Setting the Stage

Across the eastern half of the U.S., winter was fairly warm. Most states had December-February temperatures that ranked among the five warmest in the 123-period of record. February was record and near-record warm across the region, with temperatures more than 7.0°F above the twentieth-century average. Some locations even had temperatures approaching 10.0°F above average. The warm winter, and especially the warm February, caused many fruit trees to produce blooms earlier than usual.

Departures from average temperature for February 2017, as analyzed by NOAA's National Centers for Environmental Information. Source: https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/sotc/national/201702

While many across the region were basking in the early-spring temperatures, farmers and others who monitor regional agriculture knew that trouble might be on the horizon. In the recent past, including in 2007 and 2012, several of these late-winter heat waves were followed by damaging freeze events that resulted in millions or billions of dollars’ worth of damage to crops.

In addition to the threat of an early-spring freeze, the lack of cold weather during the winter also made fruit-bearing trees and bushes vulnerable to additional stresses like the freeze event. Many of the fruit-producing crops require a certain number of “chill hours,” or the amount of time the temperature is below a certain threshold, to produce a maximum yield. Peach trees typically need at least 800 hours of temperatures below 45°F to produce the highest yields. Many locations across the Southeast only observed 600 chill hours or less during the 2016-17 winter.

The times, they are a changin’

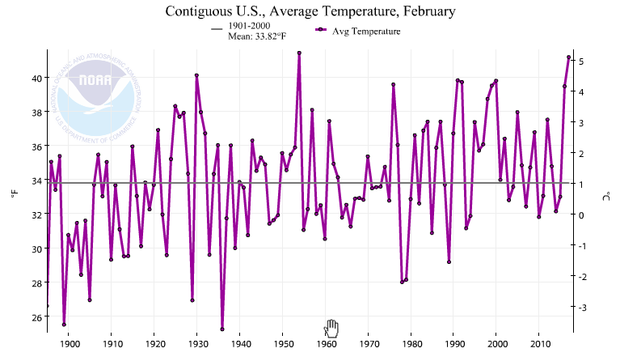

Winters are warming across the United States, especially February. Winter is warming at the fastest rate of all the seasons at 2.2°F per century since 1895. February is warming at a rate of 3.3°F per century, the fastest of any month. Meanwhile, for individual cities and towns, the average date of the last freeze has not changed much over time in the region—only by a few days in the Southeast. This means that winters are getting warmer, but we continue to see wintry weather systems that can disrupt that overall warmth, dropping the temperature below freezing into spring.

Average February temperatures for the contiguous United States for February 1895 through February 2017. The grey line represents the 20th century (1901-2000) average. From Climate at a Glance.

The Ides of March

Following the warm end of winter, many thought that the cold air wasn’t going to return to the South, or at least we hoped. Unfortunately, the weather and climate system had a different idea. On March 13, a strong cold front started to move from the Midwest into the Southeast. Behind the front, cold air originating from the Arctic began to filter into the region. Overnight and morning low temperatures during the event were as much as 25°F below average for the time of year.

The coldest morning lows were observed on the 15th and 16th. The temperature dropped into the teens in parts of the Carolinas with temperatures in the low to mid-20s across Georgia. In Gainesville, Florida, the temperature dropped to 25°F. Most locations observed several hours of temperatures below the critical threshold of 28°F, resulting in a ‘hard freeze.’ At these temperatures, little can be done to mitigate the impacts of the cold temperatures on crops that have blossomed. Farmers were only able to watch as their future harvests were devastated.

The magnitude of the cold set several station records for the date. Although the freezing temperatures weren’t that late according to the normals, some locations in the Deep South did set records for the coldest temperatures observed for this late in the season across the Deep South. The crop losses were due to a combination to the freezing temperatures as well as the incredibly warm winter and February (which caused flowers to emerge earlier than usual).

The average date of the last freeze of spring, with earlier-in-the-year dates in dark green and later-in-the-year dates in light purple. This map is based on the 1981-2010 Normals from the National Centers for Environmental Information. Map by Jake Crouch and Rocky Bilotta, NCEI.

The freezing temperatures didn’t occur that late according to the 1981-2010 normals. The average last date for a freeze in southern Georgia and northern Florida occurs between March 1 and 15, with the last freeze occurring later into April farther to the north.

Millions of Peaches

The largest impacts of the freeze were felt across Georgia and South Carolina with North Carolina, Tennessee, Alabama, Mississippi, Florida, Kentucky, and Virginia also affected on a smaller scale. In South Carolina, about 90 percent of the peaches were destroyed, with up to 80 percent of the blueberries in southern Georgia destroyed. Other crops that were affected were peaches and pears in Georgia, strawberries and blueberries in South Carolina, blueberries and peaches in North Carolina, and peaches and cherries in Virginia. In northern and central Florida, vegetable crops were damaged, with moderate-to-severe damage to the winter wheat crop across the entire region. Livestock pastures were also damaged with seasonal green up being delayed due to the freeze hitting fields already stressed with an ongoing drought.

Blueberry blossoms in Georgia, damaged by the March 2017 freeze. An unusually warm winter caused early flowering, which made many fruit crops vulnerable to a late-season freeze event. Photo used with permission of AgNet Media, Inc.

South Carolina is typically the second-largest producer of peaches in the nation annually, behind California, and just ahead of Georgia. In 2012, the United States produced 960,000 tons of peaches. Of that total, 95,000 tons were produced in South Carolina and 36,000 tons in Georgia. Using the 2012 crop statistics, if 90 percent of the 95,000 tons of peaches from South Carolina were destroyed, a minimum of 8.9 percent of the nation’s peaches were destroyed in the March freeze event. That doesn’t include the smaller losses in the surrounding states, with the actual loss likely closer to 10 percent.

The loss of peaches in the Southeast will increase prices across the nation, but the largest impacts will likely remain in the region. Anyone who lives in or has visited the south in early summer will remember the iconic road-side fruit stands that line the highways. It will be those individual farmers dealing with the loss of income while local farmer’s markets will also have shortages, driving prices even higher for local consumers.

Conclusion

Next time you are biting into a delicate peach or other fruit, take the time to consider what it took to get that delicious taste to your mouth. A farmer planted and tended to the plants, made sure soil conditions were just right, and picked then shipped the fruit to a market near to you (and even this is a major oversimplification). All of the meteorology and climatology had to be just right as well. It couldn’t be too warm, too cold, too wet, or too dry during certain stages of growth. With our changing climate, we must remain mindful that as growing conditions change, including warming winters and spring freeze events, so will our food economy.

Comments

Add new comment