NOAA's CSI Team Investigates Tornado Outbreak

The tornado outbreak across the southern United States in late April 2011 was deadly, devastating, and record breaking. These days, when the weather breaks records, it's natural to wonder if global warming is to blame. So it's not surprising that in recent weeks, climate scientists have been fielding lots of questions about the possible connection between global warming and tornadoes.

Wondering and questioning are the foundation of science, but they are only the beginning. At NOAA, the Climate Attribution Rapid Response Team (aka the "CSI" team, for "Climate Scene Investigations"), led by Martin Hoerling of the Earth System Research Laboratory, tries to move the process forward from questions to answers. Last week, the team turned their focus to tornadoes.

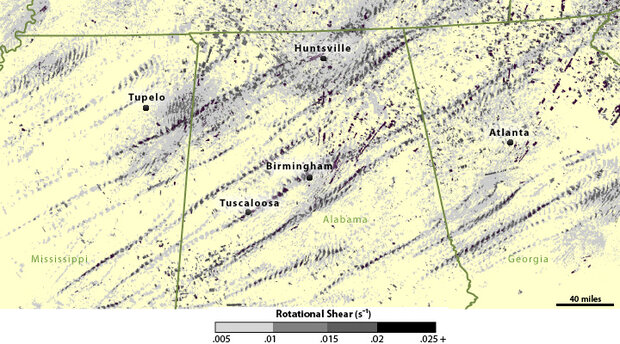

Dark streaks like tire tracks run southwest-northeast across large parts of Mississippi, Alabama, and Georgia in this map of rotational shear measured by radars between April 25-28, 2011. The streaks are not tornado ground tracks; they show where radars detected the kind of thunderstorm rotation (values above 0.01) favorable for tornado formation. (Map by Hunter Allen, based on data prepared and provided by Kevin Manross of NOAA NSSL in conjunction with Travis Smith and others working with the Warning Decision Support System Integrated Information project.)

Even before the April 2011 outbreak, scientists have been looking for long-term changes in U.S. tornado activity. The research that's already been done paints an inconclusive picture. The number of smaller tornadoes seems to have increased; the number of large tornadoes has not. Between better technology-radars, satellites, the internet-and greater public awareness, it's likely that the increase is due to more reports, not more tornadoes.

If tornado reports are biased by better reporting and detection, how would we know if global warming has affected U.S tornado outbreaks?

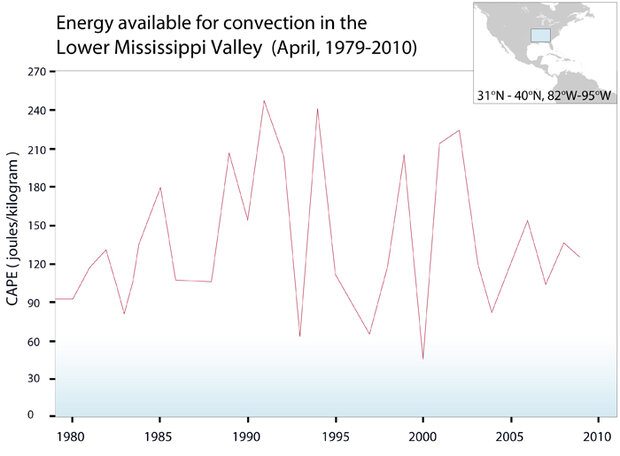

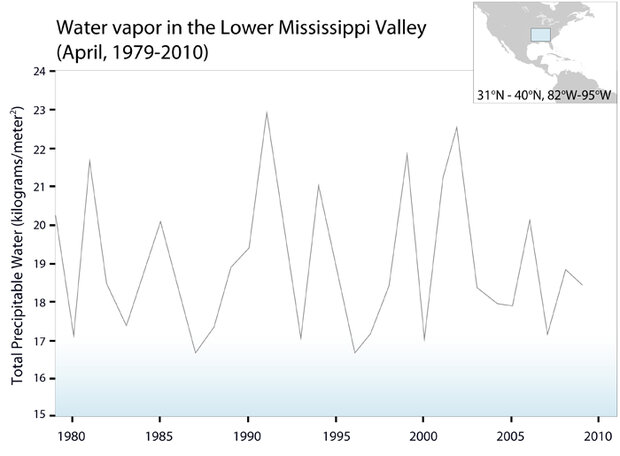

If we can't detect a change in tornadoes themselves, says Hoerling, we might be able to detect a long-term change in the weather conditions that contribute to tornadoes. Key among those factors are the instability of the atmosphere, the amount of water vapor in the part of the atmosphere known as the planetary boundary layer, and vertical wind shear.

Instability

Tornados start with thunderstorms, and thunderstorms start with convection-the rising of hot air away from Earth's surface. When a column of air is warmer at the surface than it is at higher altitudes, the air in that column is unstable. The air on the bottom is buoyant and will naturally rise, initiating convection.

An unstable atmosphere is a significant predictor of whether thunderstorms that could lead to tornadoes will happen on a given day. If the atmosphere has become more unstable in recent decades, it could affect tornado outbreaks. The CSI team compiled a record of atmospheric instability over the Gulf of Mexico and the southern United States from 1979-2010 and saw no sign of a long-term change.

Water Vapor

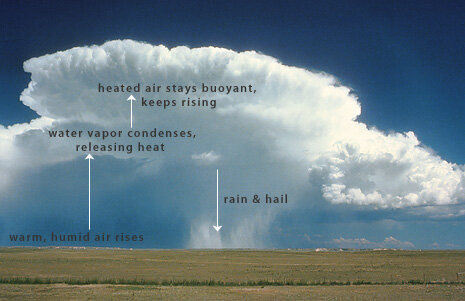

But instability alone doesn't automatically produce thunderstorms. As air rises, it cools. If there is water vapor in the air, it condenses into cloud droplets or precipitation. When water vapor condenses, it releases heat into the atmosphere. The heat makes the surrounding air buoyant, boosting the rising air even higher.

A thunderstorm generating rain and hail on the Great Plains. (Image copyright University Corporation for Atmospheric Research.)

Other weather conditions being equal, increased water vapor means more potential heat to be released through condensation and stronger updrafts, fueling potentially stronger storms. Hoerling and the CSI team have analyzed observations of water vapor over recent decades, and they don't see any long-term change in humidity over the Gulf of Mexico or the southern United States in April. The only signal they see is year-to-year variability.

Vertical shear

Even when weather conditions are favorable for thunderstorms-the air is unstable and humidity is high-it takes high vertical wind shear to generate the rotating, "supercell" thunderstorms that spawn tornadoes.

When air near the ground is blowing at one speed or direction, and air at higher altitudes is blowing at a different speed or direction, a cylinder of air in between starts to spin. Initially, this cylinder of spinning air is parallel to the ground (horizontal), but strong updrafts within the thunderstorm stand it upright. It is within this rotating thunderstorm that tornadoes form.

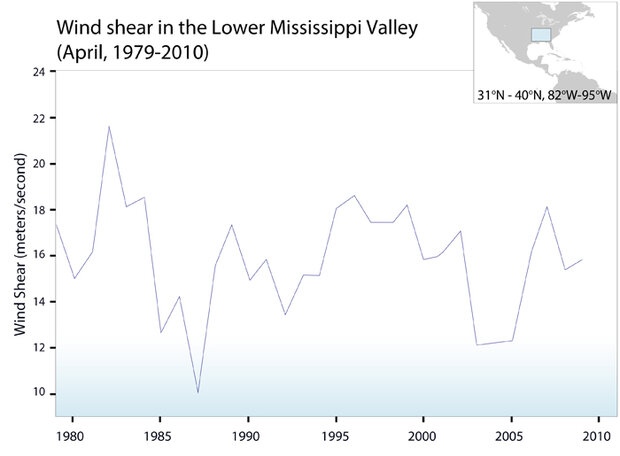

If global warming (or a naturally occurring, long-term variation) has altered wind patterns in ways that lead to more vertical wind shear over the southern United States or Gulf of Mexico in April, it might make conditions more favorable for tornadoes. So, the CSI team analyzed daily wind shear from 1979-2010. The results showed no trend, only year-to-year variability.

In their preliminary report on the analysis, the NOAA CSI team writes, "A change in the mean climate properties that are believed to be particularly relevant to severe storms has thus not been detected for April, at least during the last 30 years."

That preliminary assessment, however, isn't the same as saying "Climate change has had no impact on tornado outbreaks."

"It would take an in depth research effort," explains Hoerling, "but the next way you'd want to analyze the data would be to look at whether there has been a increase in the correlation of any of these tornado influences on a daily basis for the same time period." For example, the CSI team would like to know if it has become more likely for both instability and wind shear to be simultaneously favorable for tornado development.

The goal of the CSI team's preliminary analysis, says Hoerling, isn't to settle the question of whether tornadoes are being influenced by climate change or not. These rapid responses attempt to assemble "the best scientific information available" to provide an initial assessment to inform the public and decision makers.

The rigorous analysis and modeling required to fully explore the issue aren't things that can be done in a week or two. As Hoerling says, "We do these preliminary analysis to provide a science-based 'rapid response' to interest in these events."

Reference

Assessment of Climate Factors Contributing to the Extreme 2011 Tornadoes

![]()