Grounds of Boulder High School on September 13, following historic rainfall and flooding. By September 16, the month-to-date precipitation was already more than 1.7 times any monthly rainfall total since records began in the late 1880s. Photo courtesy Bruce H. Raup.

Through the first week of September 2013, Colorado was exceptionally warm and dry. By September 12, everything had changed. Flood conditions stretched about 150 miles, from Colorado Springs north to Ft. Collins. Saturated soils left water with no place to go, and puddles turned to ponds throughout the densely populated Colorado Front Range. Rainwater swelled rivers and creeks, overtopped dams, flooded basements, and washed out roads. By September 16, authorities had confirmed six deaths, and more than 1,000 people remained missing.

Among the hardest-hit communities was Boulder, located on the northwestern end of the Denver metropolitan area. Boulder's Daily Camera reported that heavy rains started on the evening of September 11 and continued through the following morning. The National Weather Service recorded rainfall amounts exceeding 8 inches in Boulder on September 12, and amounts exceeding 4 inches the next day. Meteorologist Jeff Masters noted on his blog that the three-day rainfall recorded by the evening of September 12 exceeded the monthly total for any month since rainfall records began in 1897. Similarly high rainfall totals occurred in other spots along the Front Range. Masters exclaimed, "These are the sort of rains one expects on the coast in a tropical storm, not in the interior of North America!"

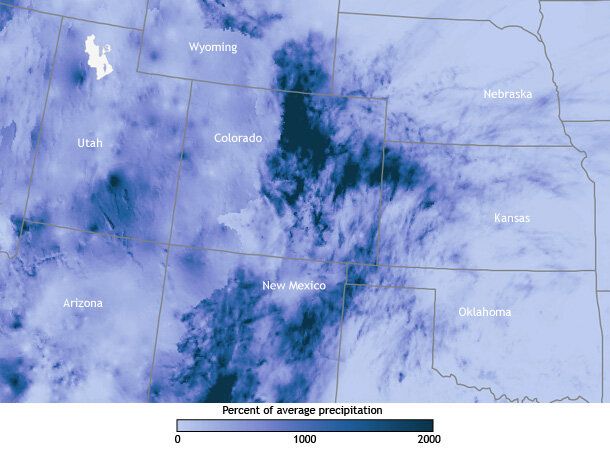

Percent of normal rainfall over the U.S. West between September 10-16, 2013. Part of Colorado received more than 1000% of their normal rainfall for this time of year. Based on data from the NWS Advanced Hydrologic Prediction Service.

In an interview with KDVRDenver, Russ Schumacher of Colorado State University concluded that the precipitation in Boulder County and other parts of the state qualified as a 1,000-year event, meaning that any one year has just a 1-in-1,000 chance of experiencing such heavy precipitation. Ranking the actual flooding is more challenging than quantifying the precipitation because over time, people use the land differently. Bob Henson of the University Corporation for Atmospheric Research remarked in AtmosNews, "An identical weather event a century ago might produce a much different flood than the same event today."

On September 12, the Boulder Creek, which flows roughly eastward through town, crested in downtown Boulder at 7.78 feet—the highest water level observed at that location since 1894. The main highway running through Boulder was partially closed southeast of town, and partially destroyed northwest of town, isolating the nearby mountain community of Lyons. Thousands of residents faced power outages and evacuation orders in the Denver-Boulder area as officials called in the National Guard to assist rescue efforts. Schools, businesses, and government offices closed. Many roads remained closed and impassable, so multiple mountain communities remained isolated. And the rain kept falling.

As the rain continued, heavy humidity hung in the air. Precipitable water—the height of liquid water that would result if all the water vapor in the atmospheric column were condensed—showed record-high measurements for this time of year, as recorded by balloon soundings from the National Weather Service Storm Prediction Center. Masters noted that the region's highest September precipitable water measurements, dating back to 1948, occurred on September 12-13, 2013.

Boulder is no stranger to floods. In fact, it is one of Colorado's most flood-vulnerable communities. The city is situated at the mouth of a canyon, and the Boulder Creek flows through the middle of town. According to weather historian Christopher C. Burt, floods pummeled Boulder in 1894, 1896, 1906, 1909, 1916, 1921, 1938, and 1969. The worst floods struck in 1894 and 1969. But those floods occurred in the springtime: May 31-June 2, 1894, and May 7, 1969.

Paved bike/pedestrian paths line the Boulder Creek throughout the city, and many residents use these paths for their daily commutes. On September 12, 2013, the creek path was under fast-moving water. Photo courtesy Bruce H. Raup.

Boulder's 2013 flood not only brought unusual rainfall, it came at an unusual time. On average, April and May are Boulder's wettest months, with precipitation totals of 2.45 and 3.04 inches, respectively, between 1948 and 2005, according to the Desert Research Institute. Precipitation amounts drop slightly in the summer months, but remain relatively high as the North American Monsoon takes hold sometime between June and August. Monsoon winds carry moisture from the Gulf of Mexico northward over the American Southwest. Monsoon storms can bring strong afternoon and evening thunderstorms to the state. Although not the driest month of the year, September is usually much more arid, with average total precipitation of 1.61 inches.

Like summertime monsoon storms, the deluge that struck in the second week of September 2013 involved moist air from the Gulf of Mexico. The storm resulted from the interaction of low pressure, warm air loaded with moisture, and Colorado's mountains. After the 90+-degree weather in the first week of September, cool, wet weather moved into the state, leaving the ground saturated by September 11. Meanwhile a low-pressure system centered over Utah and Nevada started air moving in a counter-clockwise direction over the Southwest. This pulled warm, moisture-rich air from the Gulf of Mexico into Colorado from the southeast. As the air traveled up the eastern face of the Rockies, it formed clouds and then rain, and remained in place for days.

The September flood eroded banks. This eroded ban exposed a gas line on September 13, 2013. Photo courtesy Bruce H. Raup.

As for whether a warming climate played a part in this historic storm, Henson described the event as an "excellent candidate for an attribution and detection study." Computerized climate models enable scientists to test how frequently similar storms might occur with or without fossil fuel use. Although it stands to reason that a warming climate could worsen storm intensity since a warmer atmosphere can hold more moisture, Henson cautioned, "Even when researchers find that a given type of disaster has become more likely, a rare event is still going to be rare—and it can occur without any help from greenhouse gases."

By September 13, the rain was starting to ease around along the Front Range. But a multitude of damaged or destroyed buildings, waterlogged vehicles, and washed-out roads and bridges meant that Colorado residents would be mopping up for weeks or months after the skies cleared.

References

Advanced Hydrologic Prediction Service. (2013, September 16). Boulder Creek at Boulder. National Weather Service. Accessed September 16, 2013.

Brennan, C., Mattern Clark, E. (2013, September 12). Boulder registers wettest 24-hour period, and month, on record. Daily Camera. Accessed September 13, 2013.

Burt, C.C. (2013, September 12). Catastrophic flood in Boulder, Colorado. Weather Underground. Accessed September 13, 2013.

Desert Research Institute. Boulder Monthly Climate Summary, Period of Record : 8/ 1/1948 to 12/31/2005. Accessed September 13, 2013.

Earth System Research Laboratory. Boulder Daily Climatology and Daily Records. NOAA. Accessed September 13, 2013.

Erdman, J. (2013, September 12). Colorado flash flooding: How it happened, fow unusual? The Weather Channel. Accessed September 13, 2013.

Henson, B. (2013, September 14). How much rain fell on the Front Range, and how historic was it? AtmosNews. Accessed September 16, 2013.

Masters, J. (2013, September 13). Boulder's 1-in-100 year flood diminishing. Weather Underground. Accessed September 13, 2013.

Mitchell, K., McGhee, T., Draper, E. (2013, September 15). Little relief from Colorado floods with six dead and 1,253 unaccounted for. The Denver Post. Accessed September 16, 2013.

9News. (2013, July 8). Colorado Weather Forecast: Daily thunderstorms become more common with monsoon moisture. Accessed September 13, 2013.

Pearson, M., Howell, G. (2013, September 13). 'Not over': Heavy rainfall heading once more for flooded Colorado. CNN. Accessed September 13, 2013.

Simpson, D., Pearson, M., Cabrera, A. (2013, September 12). Colorado floods: 3 dead, 1 missing, rescue efforts continue amid rain. CNN. Accessed September 13, 2013.

Storm Prediction Center. Observed Sounding Archive. National Weather Service. Accessed September 16, 2013.

Weather Forecast Office. Denver Boulder. National Weather Service. Accessed September 16, 2013.