Bracing for Heat

The long, hot days of summer come with outdoor activities and much needed vacation for many Americans. Public health officials, however, remain on high alert during the warm days: they are increasingly aware of the increased exposure to extreme heat that accompanies summertime activities and the threats faced by residents of buildings without air conditioning. They're also mindful of the need for extra protection of vulnerable populations during heat waves.

Health officials in Minnesota have made it easy for communities of all sizes to implement a heat health plan. Check out how they are Building Resilience Against Climate Effects. U.S. Climate Resilience Toolkit video.

Building resilience to extreme heat for the range of rural, urban, economically disadvantaged, and wealthy communities across an entire state presents a formidable challenge. While Minnesota is a state that is more commonly known for its frigid winters than its warm summers, it has occasionally experienced summer heat waves that linger for several days. In response, cities and towns across the state have taken strides to meet the challenge of protecting their residents when heat waves occur.

A customizable community toolkit

Building on lessons learned over several summers, Kristin Raab—Health Impact Assessment and Climate Change Program Director in the Environmental Health Division of Minnesota’s Department of Health—packaged information from diverse communities into a cohesive toolkit that communities of all sizes can use to prepare for heat waves. The Minnesota Extreme Heat Toolkit describes changing weather conditions in Minnesota, the magnitude of potential health consequences from extreme heat, and key steps communities can take to prevent heat-related illnesses and deaths.

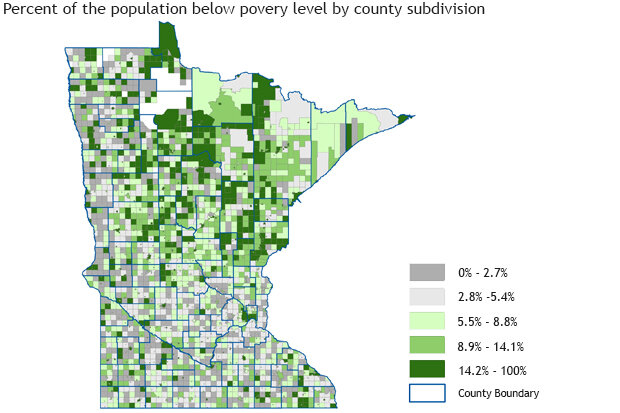

Decision makers can identify where to focus their resilience-building efforts by identifying where relatively high numbers of vulnerable people live.This map shows the percentage of the population below the poverty line by county. The darker the color the higher the percentage. Courtesy the Minnesota Department of Health.

The toolkit acknowledges that extreme heat response plans will vary with the size of the community and the habits of its residents: examples from the mostly rural Olmsted County and the urban centers of Saint Paul and Minneapolis illustrate a range of community plans that could be useful in Minnesota and beyond.

Right-sized planning

Olmsted County in southeastern Minnesota is home to a generally healthy, largely rural population. After a resident died during an excessive heat event in the early 2000s, though, Olmsted County’s Public Health Services reconsidered their emergency management plan and included provisions for extreme heat events. In 2010, for instance, the county offered access to centralized cooling centers during extremely hot days, but they found that residents did not take advantage of them. Planners went back to the drawing board to find simpler solutions to keep people cool.

Today, when the NOAA National Weather Service issues an advisory or warning for an excessive heat event, public service announcements on radio and television stations in the county suggest that people who don’t have air conditioning head to cool locations—such as libraries, shopping centers, or senior centers. Additionally, the Mayor of Rochester, the county seat, may use discretion to offer free bus rides to those locations. As some people do not tune in to media, the county’s Health Services staff also distributes flyers through non-governmental organizations such as Meals on Wheels. Amy Evans, the County Emergency Preparedness Coordinator, and her team review their strategies each year and consider new ideas to protect residents.

Urban challenges

Saint Paul, Minnesota skyline. Photo Credit: Flickr user xnatedawgx via CC license.

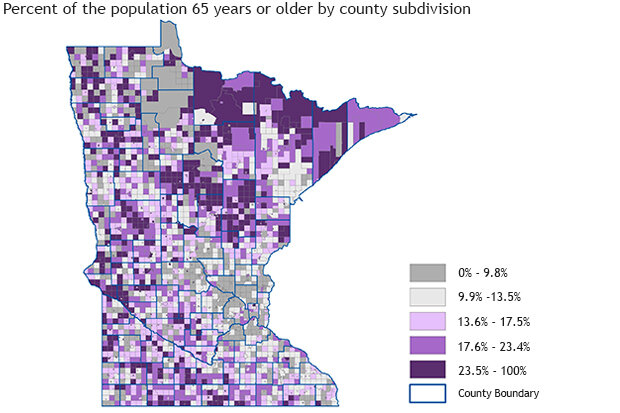

Saint Paul, the state capital, has different challenges: maps of census data show the city has a large population of people over the age of 65. Robert Einweck, the Health Protection Division Manager for Ramsey County, recognizes that this age group has fewer metabolic defenses from the ill effects of heat than the general population. He relies on both public officials and community partners to help protect older populations. The county pushes automated email messages to many of its service providers, encouraging them to contact vulnerable clients during heat events and get them to cool locations.

This map shows the percentage of the population 65 years or older by county. The darker the color the higher the percentage. Courtesy the Minnesota Department of Health.

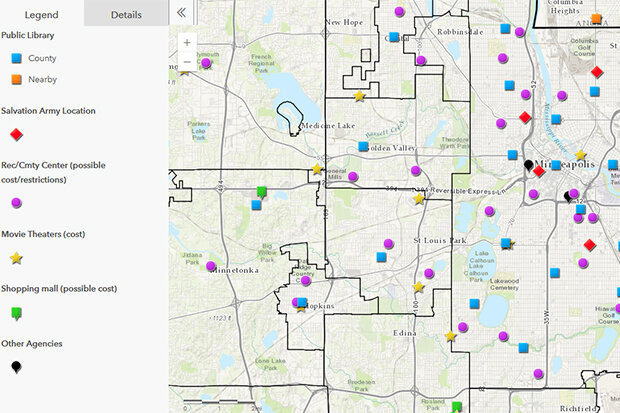

To protect the full range of residents in the county, the Health Protection Division also provides maps highlighting locations where people can access air conditioning. They show public facilities such as libraries, as well as privately owned settings such as shopping malls and cinemas. And when heat waves occur, the Mayor’s office often authorizes extended hours for pools and recreation centers. Einweck and colleagues also developed a translation system, called ECHO, that provides emergency warnings in Spanish, Hmong, and Somali so that language isn’t an obstacle to effective outreach and communication.

Incorporating humidity to characterize heat

Pam Blixt, Emergency Preparedness Manager in the neighboring, larger “twin city” of Minneapolis, was a co-creator of ECHO. Blixt is working with her department’s staff meteorologist to shift their warning system from simple measures of heat to a measurement that incorporates humidity and, therefore, the intensity of heat exposure. Her suggestion is to monitor “wet bulb” temperature, the same measure the U.S. military monitors while conducting military exercises. To support this improvement, Hennepin County has deployed a network of sensors to supplement official NOAA weather stations so that higher-resolution measures of temperature and humidity are available in real time.

Hennepin County's Cooling Options map highlights locations where residents can go to cool down. Libraries, community centers, and shopping malls are shown on the map.

Blixt’s department also developed a mobile app that encapsulates many of the strategies that smaller communities use, including maps of cool places people can go during heat waves. Their notification network includes over 500 agencies and organizations that deliver services throughout the community. Broadcast meteorologists in Minneapolis also help spread educational information before and during heat waves. Additionally, the city’s extreme heat website provides information, such as a list of medications that may increase the effects of extreme heat, descriptions that can help people recognize the signs of heat sickness, and emergency contact numbers.

Building on others’ successes

One conclusion from government agencies of all sizes is that good communication with NOAA’s forecast offices is an essential first step to preparing for extreme heat events. The National Weather Service is the key source of information that catalyzes a cascade of varying responses, and those responses vary depending on the size of the community where they are implemented. The Minnesota Department of Health’s Extreme Heat Toolkit includes adaptation examples and a draft response plan to help health officials and emergency managers beat the heat.

This article was originally published as part of the U.S. Climate Resilience Toolkit's "Case Studies" section. As part of the toolkit, users can learn about the effects of extreme heat on health with the National Integrated Heat Health Information System (NIHHIS).